4.8 Protein secretion from the cell

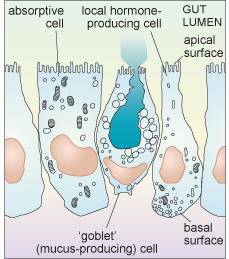

Intestinal epithelial cells are a good example of the diversity of secretory function. The intestinal epithelium contains many cells that are specialised for absorption (and have a small Golgi apparatus and only a few secretory vesicles), but it also includes several different types of cell that are specialised for secretion. Some of these cells secrete digestive enzymes from their apical surface which is exposed to the intestinal lumen (where ingested food is located); different enzymes are secreted in different parts of the gastrointestinal tract. Cells of another type secrete heavily glycosylated proteins known as proteoglycans into the lumen of the intestine. These mix with water to form mucus which acts as a lubricant, aiding the passage of material along the gut. Yet other epithelial cells secrete local hormones, from the other surfaces of the cell (the basolateral sides. i.e. base (basal) and side (lateral)) that are in contact with other cells. These hormones are secreted either into blood vessels or close to the surface of nearby cells.

Each type of intestinal epithelial cell is therefore polarised; it is not uniform, either in shape or function, as shown schematically in Figure 20.

Another factor that is important to think about when considering the secretion of molecules from cells is the difference in demand for different types of exported molecules. For example, some substances are constantly delivered to the cell membrane, and are continuously released in small quantities all the time. This sort of release is known as constitutive secretion. An example is the secretion of mucus from intestinal epithelial cells. Other molecules, however, are only released at certain times, in response to some kind of signal. This type of release is known as regulated secretion. An example of regulated secretion is that of gastrointestinal hormones and digestive enzymes, which are released in response to ingestion of food.

Within each of these three types of intestinal epithelial cell, a complex sorting and delivery system exists. All the membrane-associated and secretory proteins are synthesised in the RER, processed and packaged in the Golgi, and then they continue by transport in vesicles along the cytoskeleton to the cell membrane. What about the mechanism by which molecules are actually released from cells? This involves a process known as exocytosis. During exocytosis the vesicle membrane fuses with the cell membrane, releasing the vesicle contents outside the cell.

What is the general term for the converse process, in which extracellular materials are ingested by engulfment by extensions of the cell membrane which form into vesicular structures within the cytosol?

The term is endocytosis.

You have already learnt that organisms such as amoebae feed by endocytosis (sometimes referred to as phagocytosis when it involves larger particles such as bacteria). Cells of the immune system, known as phagocytes, also ingest bacteria in this way. What is the fate of the materials that the cell ingests? They are broken down by yet another type of organelle, the lysosome.