1.4.3 Covalent structures and bonding

A covalent bond is formed when two atoms share two electrons, through overlap and merging of two electron orbitals, one from each atom (Figure 12c). Crystals containing covalent bonds tend to have more complex structures than those of ionic or metallic structures. Covalent bonding requires the precise overlap of electron orbitals, so if an atom forms several covalent bonds, these are usually constrained to specific directions. As covalent bonds are directional, unlike metallic or ionic bonds, this places additional constraints on the arrangements of atoms within such a crystal. One result is that covalent structures tend to be more open - and hence have lower densities than metallic or ionic structures.

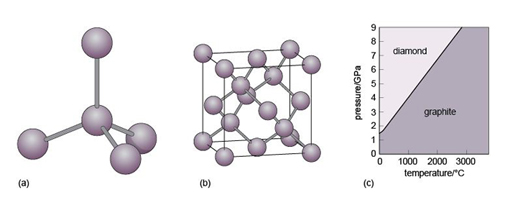

Diamond is an example of a covalently bonded solid. In this form of carbon, each atom is covalently bonded to four other carbon atoms, arranged at the corners of a tetrahedron (Figure 16a). The resulting structure, which has a repeating cubic shape, is illustrated in Figure 16b. The structure contains much more unoccupied space than close-packed metal structures.

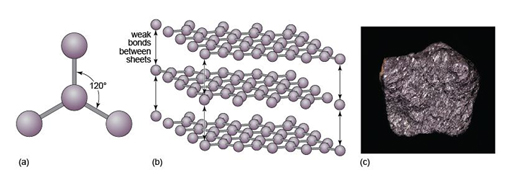

Another form of solid carbon with covalent bonding is graphite. Unlike those in diamond, the carbon atoms in graphite are covalently bonded to three neighbours in the same plane (Figure 17a), producing a strong sheet of carbon atoms. However, each carbon atom has one extra electron available for bonding that forms very weak bonds, which serve to keep the carbon sheets together (Figure 17b).

-

How do the crystal structures of diamond and graphite account for the differences in hardness between the two minerals?

-

Diamond has a three-dimensional bonding pattern, with identical bonding in all directions, and no 'weak' directions. Graphite has a mainly two-dimensional pattern, with sheets of C-C bonds. Bonds between the sheets are very weak, so sheets can easily slide past each other, explaining graphite's use as a lubricant and why it is soft enough to mark paper.

Diamond and graphite have the same chemical composition (pure carbon) but different crystal structures. They are known as polymorphs of carbon. Diamond is formed under higher pressures than graphite (Figure 16c), and is less stable than graphite at the surface of the Earth. However, because of the strong bonding, it is very difficult to break down the diamond structure, so diamonds (fortunately) will not spontaneously transform into graphite! Note that not only is diamond harder than graphite, but it is also denser, as predicted by its structure (Table 3).

| Substance | Relative density at room conditions(compared with water = 1.0) | Structure and bonding |

|---|---|---|

| ice, H2O | 0.9 | open structure; covalent bonds plus weak bonds between H2O molecules |

| graphite, C | 2.2 | open structure; covalent bonds plus weak bonds between layers |

| feldspar, KAlSi3O8 | 2.5 | open structure; predominantly covalent bonds |

| quartz, SiO2 | 2.7 | open structure; predominantly covalent bonds |

| olivine, Mg2SiO4-Fe2SiO4 | 3.2-4.4 | structure based on close-packing, but with ionic and covalent bonds. Density increases as Fe content increases |

| diamond, C | 3.5 | structure based on close-packing, but with covalent bonds |

| barite, BaSO4 | 4.5 | ionic bonds between barium and sulfate groups |

| hematite (iron oxide), Fe2O3 | 5.3 | structure based on close-packing; ionic and metallic bonds |

| galena (lead sulfide), PbS | 7.6 | structure based on close-packing; ionic and metallic bonds |

| silver, Ag | 10.5 | close-packed structure; metallic bonds |

| gold, Au | 19.3 | close-packed structure; metallic bonds |

Minerals are never chemically pure; they always contain some foreign atoms. These impurity atoms may simply squeeze into the interstices. Another possibility is that certain elements may be able to directly replace (substitute for) the normal atoms in the ideal structure - although, for a comfortable fit, the substituting element must have a similar size and charge to the original atom. This phenomenon is called ionic substitution. An example is the substitution of Fe2+ for Mg2+, or Mg2+ for Fe2+, which occurs in the mineral olivine (Section 3.3.1).