1.1 Defining influenza

How would you define ‘influenza’?

You may well have defined influenza as an infection caused by an influenza virus. However, you may have defined it according to its symptoms: an infection that starts in the upper respiratory tract, with coughing and sneezing, spreads to give aching joints and muscles, and produces a fever that makes you feel awful; but usually it has gone in 5–10 days and most people make a full recovery.

The first answer here is the biological definition and, in the Open University course SK320, diseases are defined according to the infectious agent which produces them. This is because different infections can produce the same symptoms, and the same infectious agent can produce quite different symptoms in different people, depending on their age, genetic make-up or the tissue of the body that becomes infected. Here a distinction is made between the infectious disease caused by a particular agent and the disease symptoms.

Unfortunately there is a lot of confusion in common parlance about different diseases. Often, people say that they have ‘a bit of flu’ when they have an infection with some other virus, or a bacterium that produces flu-like symptoms. Such loose terminology is understandable, since most people are firstly concerned with the symptoms of their disease. But to treat and control disease requires accurate identification of the causative agent, so this is the starting point for considering any infectious disease.

Attributing cause to a disease

The difficulties encountered in assigning a particular pathogen to a disease are well-illustrated by influenza.

During the influenza pandemic that occurred in 1890, the microbiologist Pfeiffer isolated a novel bacterium from the lungs of people who had died of flu. The bacterium was named Haemophilus influenzae and since it was the only bacterium that could be regularly cultivated from these individuals at autopsy, it was assumed that H. influenzae was the causative agent of flu.

Again, in the 1918 flu pandemic, the bacterium could be regularly cultivated from people who had died of flu with pneumonia. So it was thought that flu was caused by the bacterium, and H. influenzae came to be called the ‘influenza bacillus’.

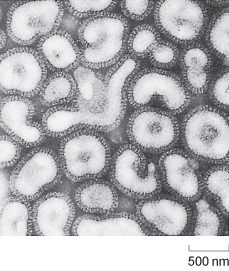

The role of H. influenzae was only brought into question in the early 1930s, when Smith, Andrews and Laidlaw showed that it was possible to transfer a flu-like illness from the nasal washings of an infected person to ferrets, using a bacteria-free filtrate. These studies demonstrated that the pathogen was in fact much smaller than any known bacterium and paved the way to the identification of influenza viruses (Figure 1).

Why do you suppose that H. influenzae was incorrectly identified as the causative agent of flu?

The bacterium fulfils two of Koch’s postulates: it is regularly found in serious flu infections and it can be cultured in pure form on artificial media. Moreover, at that time no-one knew what a virus was, and everyone was thinking in terms of bacterial causes for infectious diseases.

Although the precise role of H. influenzae in the 1890 and 1918 flu pandemics is not clear, it is likely that the bacteria were present and acting in concert with the flu virus to produce the pneumonia experienced. Such synergy between virus and bacteria was demonstrated by Shope in 1931. He infected pigs with a bacterial-free filtrate (containing swine influenza virus) with or without the bacteria, and showed that the disease produced by the bacteria and filtrate together was more severe than that produced by either one alone (Van Epps, 2006).

In its role of co-pathogen, H. influenzae is only one of a number of bacteria that can exacerbate the viral infection. This highlights a very important point. In the tidy world of a microbiology or immunology laboratory, scientists typically examine the effect of one infectious agent in producing disease. In the real world, people often become infected with more than one pathogen. Indeed, infection with one agent often lays a person open to infection with another, as immune defences become overwhelmed. For this reason, a particular disease as seen by physicians may be due to a combination of pathogens.