1.2 2 The chromosomes that constitute the human genome

Laboratory techniques are available to aid in the preparation and staining of the chromosomes from a single cell, so that they are readily distinguished and can be photographed under the microscope. During mitosis, the chromosomes become visible (because they have condensed) and it is during mitosis that chromosome number, size and shape can be most easily studied. Every species has a particular number of chromosomes, each with a characteristic size and shape. For example, chimpanzee cells have 48 chromosomes, turkey cells have 82, and the cells of some species of ferns have over 1000 chromosomes!

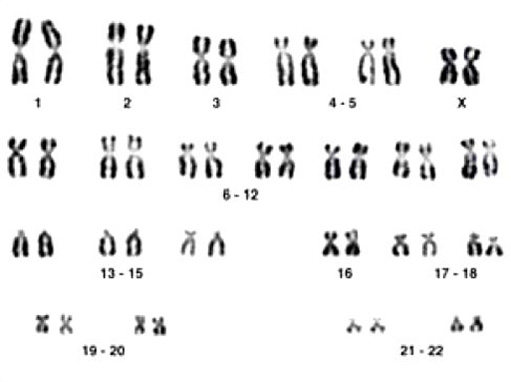

Figure 2.1 shows the chromosomes of a human female, arranged to reveal their features. This distinctive pattern is described as the human female karyotype, that is, the pattern of chromosomes that is unique to human females. The same term, karyotype, is used for the standard chromosome set of an individual, as in ‘human female karyotype’, or of a species, as in ‘human karyotype’. (Each chromosome in Figure 2.1, consists of two chromatids about to separate, one into each of two new cells.)

SAQ 1

What is the most striking feature of the human chromosomes shown in Figure 2.1?

Answer

The 46 chromosomes are present as 23 pairs of various sizes; the members of each pair look the same.

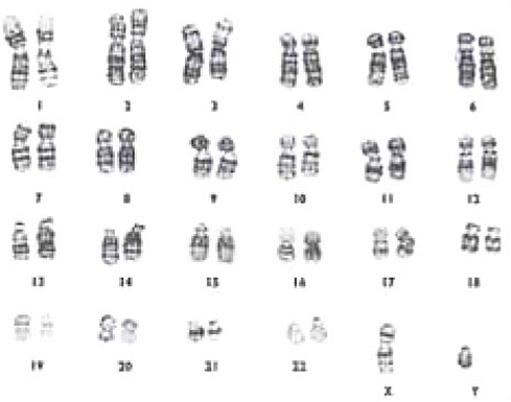

The chromosomes in 22 of the pairs have been given a number starting with the largest and progressing to the smallest. Thus, there is a pair of chromosome 1, a pair of chromosome 2, etc. Members of a pair are said to be homologous, which means ‘having a similar structure’, thus there are 22 homologous pairs of chromosomes. Although the chromosomes of some homologous pairs are longer or shorter than others, it is still difficult to distinguish between several pairs of chromosomes on this criterion alone. For example, look at the pairs of chromosomes numbered 6 to 12 in Figure 2.1: if those chromosomes were mixed up it would be difficult to separate them into pairs again on the basis of visual appearance alone. This difficulty was overcome in the 1970s by the discovery of special staining techniques that produce distinctive patterns of bands on chromosomes (Figure 2.2).

Such techniques have made it possible to define the differences between the members of one pair and those of another, as shown in Figure 2.2. The chromosomes of a human male, arranged as a karyotype, could be from any cell in the body (with a few exceptions).

SAQ 2

How does the human female karyotype (Figure 2.1) differ from the human male karyotype (Figure 2.2)?

Answer

The female karyotype has two X chromosomes whereas the male has one X chromosome and a small Y chromosome.

The X and Y chromosomes are called sex chromosomes because they play an important role in sex determination: females with a pair of homologous X chromosomes are described as XX, and males are described as XY. Apart from these sex chromosomes, both males and females contain similar sets of 22 homologous pairs of non-sex chromosomes, or autosomes.

SAQ 3

In Figure 2.1, what does the banding pattern of the homologous pairs of chromosomes numbered 6–12 reveal?

Answer

First, each pair can be distinguished from all other pairs, and second, each chromosome appears to have an identical banding pattern with its partner.

The two observations that you have just made about chromosomes reveal important information about inheritance. We will look at the implications of each of these observations in turn.

Each of the 24 different kinds of chromosome that may occur in a human cell (that is, chromosomes 1 to 22, plus X and Y) carries different genes; each has particular genes arranged in a specific order along its length. However, both partners in a pair of homologous chromosomes, for example the pair of chromosome 1, carry the same genes in the same order. This means that each gene along the 22 autosomes, and the X chromosomes in females, is present twice in the nucleus of almost all cells, a feature that has important consequences for inheritance. Furthermore, the set of genes is the same in all humans.

Different chromosomes contain different genes, but the partners in a pair of homologous chromosomes carry the same genes in the same order along their lengths.

Figure 2.3 shows that the two sex chromosomes look quite different from each other. They also carry different genes and, given the small size of the Y chromosome, you may not be surprised to learn that it contains very few genes, the most important of which is the gene that carries instructional information for the development of testes (male reproductive glands; singular testis) rather than ovaries (female reproductive glands; singular ovary).