1.3 Edward Jenner and vaccination with cowpox

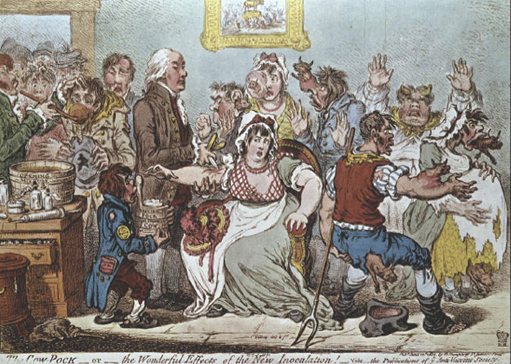

Vaccination originally meant deliberate infection with the cowpox virus (vaccinia), which is responsible for a relatively benign infection on the udders of cows and can be transferred to people, where it usually causes pustules on the hands. However, serious complications can ensue in a minority of cases. Vaccination with cowpox developed from an experiment carried out by an English country doctor, Edward Jenner (Figure 1). He had heard the common folklore that milkmaids who became infected with cowpox appeared to be protected from smallpox, and it had been previously reported that people who had recovered from cowpox did not develop the usual skin reaction to variolation. In 1796, Jenner deliberately infected an eight-year-old boy with the cowpox virus and repeated the experiment on ten others in the next two years. He confirmed that these vaccinated subjects did not respond to smallpox variolation and, despite initial resistance (Figure 2), his work ushered in the era of protective immunisation. In honour of Jenner, the term vaccination became widely used for any procedure in which the aim is to produce or enhance immunity to an infectious agent. In this course, we follow this tradition, but note that vaccination and immunisation are equivalent terms in current usage.

Activity 3

The type of vaccination developed by Jenner used one kind of pox virus to produce immunity against another. How can an immune response against one antigen or pathogen be effective against another? Does this not go against the idea that immune responses are ‘specific’?

Answer

An antibody that binds to an epitope (a particular molecular shape) on one antigen will also bind to another antigen if it shares an identical epitope, or a very similar one. Two viruses may have sufficiently similar epitopes that an antibody raised against one will also bind to the other. Antibody specificity is not absolute.

Although it was the first to be discovered, this type of vaccination – using one pathogen to protect against another with which it cross-reacts – is quite unusual. Much more common is the use of killed pathogens, or a harmless variant of the pathogen, or one of its component antigens, to induce immunity without producing disease. We look at modern methods of vaccine production in Section 4.