6.2 Zoonoses

Eradication of a disease is a splendid aim, but although vaccines exist against some important zoonotic diseases (e.g. tuberculosis), this goal is extremely difficult or even impossible to achieve for zoonoses. The situation is well illustrated by the viral zoonoses such as yellow fever. An effective vaccine has been available against yellow fever virus for several decades, but the WHO estimates there are still at least 200,000 cases per year with 30,000 deaths (WHO, 2001). The virus is present in monkeys in equatorial Africa and South America and is transmitted from monkeys to humans principally by mosquito bite. It is clearly impossible to eradicate the virus, because there is a very large natural host population of monkeys in which it will persist. Also, the female mosquitoes can transmit the virus ‘vertically’ to their offspring in their eggs, maintaining its presence in the vector population.

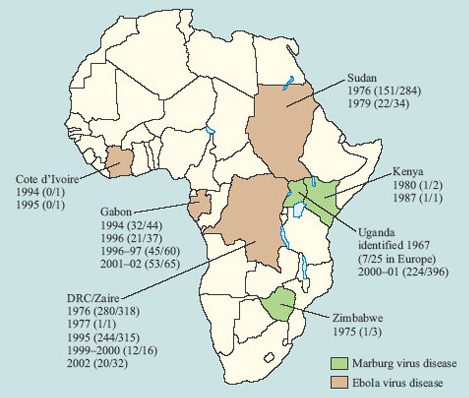

Over 200 viruses fall into the category of zoonotic infections (Taylor, 2001), including some of the most lethal human infections ever identified. They include Lassa fever, Hanta virus pulmonary syndrome, Ebola fever and Marburg disease. Fortunately, the incidence of human infection with these diseases is still very low and usually sporadic, but case fatality levels are typically 50–80 per cent (as Figure 9 illustrates). In epidemics, human-to-human transmission readily occurs among close contacts of the original case, but strict quarantine measures have (so far) contained the outbreaks, although complete control has sometimes taken over a year. Nevertheless, the episodic recurrence shown in Figure 9 demonstrates the potential dangers of a large pool of ‘animal’ viruses, either transmitting infection to humans directly or acting as a source for the development of new human viruses.

Although it would be desirable to have vaccines against high-fatality viral zoonoses, the animal reservoirs of infection will always be present. Moreover, there are a number of other factors which mean that vaccine development is of relatively low priority. Firstly, if the disease is very rare, the financial incentive for a company to develop a vaccine is lacking. Secondly, there are such a large number of zoonotic viruses that it is difficult to know where to start. An individual who is planning to travel in an area where the infections are found might have to be immunised against a wide range of viruses. Despite these factors, some vaccine development is underway for viral haemorrhagic diseases, since they would be of particular value to health care workers involved in controlling epidemics.