1 Machines

1.1 The tool-building animal

It seems that one of humanity's most persistent dreams has been of artificial creatures, lifelike creations with the characteristics and powers of animals or humans: intelligent machines that are our servants, partners and even occasionally our enemies. Writing perhaps eight hundred years before the birth of Christ, the Greek bard Homer tells of how:

Huge god Hephaestus got up from the anvil block

with laboured breathing.

At once he was helped along

by female servants made of gold, who moved to him.

They look like living servant girls, possessing minds,

hearts with intelligence, vocal chords, and strength.

They learned to work from the immortal gods.

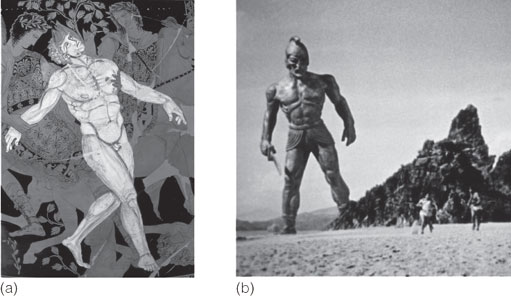

Hephaestus himself had built these beautiful robotic servants. He also created Talos (Figure 1), a gigantic mechanical man of bronze, the guardian of Crete, who ran round the entire coast of the island three times a day (this equates to a speed of 250 miles per hour!) and hurled great rocks at suspected intruders.

Nearly three thousand years later, Isaac Asimov imagined a world entirely run by benevolent, all-knowing machines in this dialogue between characters in his short story The Evitable Conflict':

'... Stephen, if I am right, it means that the machine is conducting our future for us ... How do we know what the ultimate good of humanity will entail? We haven't at our disposal the infinite factors that the Machine has at its! ... We don't know. Only the machines know and they are going there and taking us with them.'

'But are you telling me, Susan, that... humanity has lost its own say in its future?'

'It never had any really. It was always at the mercy of economic and sociological forces it did not understand ... Now the Machines understand them; and no one can stop them, since the Machines will deal with them ... having, as they do, the greatest of weapons at their disposal, the absolute control of our economy.'

'How horrible!'

'Perhaps how wonderful! Think, that for all time all conflicts are finally evitable. Only the Machines, from now on, are inevitable!'

Whether you find such visions sinister or benign, history, literature and myth are littered with tales of artificial men and animals: slaves, enemies or merely curiosities. It's worth taking a brief look at a few of these in order to make some serious points about this dream.

Exercise 1

Spend about twenty minutes searching the Web to find some other examples of artificial creatures down the ages – in reality, legend, myth or fiction. Think carefully about alternative search terms before starting your search.

Comment

It didn't take me long to come up with the following:

- The Golem. Jewish myths of the Golem became popular around the 10th century. In the best-known version, Rabbi Yehudah Levi ben Betzalel of Prague created an artificial man from river clay spread over a frame of tree branches and rags, to act as servant and protector of the city's Jewish poor. The Golem was brought alive by holy words chanted by the Rabbi. It could not speak, but understood and obeyed verbal commands written by the Rabbi on a piece of paper and placed in its mouth. The Golem developed a human personality, becoming proud and oppressive towards the very people it was supposed to protect. Eventually it had to be destroyed by its creator.

- Talking heads. In the 13th century, both the philosopher Albertus Magnus and the English scientist and monk Roger Bacon were rumoured to have created heads that could talk, dismissed as sacrilegious abominations by their contemporaries. By the late 16th and early 17th centuries, fake talking heads were appearing all over Europe. The novelist Miguel de Cervantes's hero Don Quixote and his squire Sancho Panza encounter one:

The last questioner was Sancho, and his questions were, 'Head, shall I by any chance have another government? Shall I ever escape from the hard life of a squire? Shall I get back to see my wife and children?' To which the answer came, Thou shalt govern in thy house; and if thou returnest to it thou shalt see thy wife and children; and on ceasing to serve thou shalt cease to be a squire.'

'Good, by God!' said Sancho Panza; 'I could have told myself that ..."

The effect is brought about by means of a tube down to the floor below. Talking machines are now commonplace, as anyone who has stepped into a lift recently can confirm.

Automata. Around 1495 Leonardo da Vinci constructed an automaton in the form of an armoured man, capable of moving its arms and head, sitting up, and simulating speech by opening and closing its mouth. However, the 18th century was the true golden age of automata, intricately built mechanical creatures, sometimes with amazing capabilities. The prince among automata builders was Jacques de Vaucanson (1709–1782), whose machines were displayed all over Europe, to kings and scientists, nobles and commoners. Voltaire described him as 'bold Vaucanson, rival to Prometheus', a man with the power to create life. Vaucanson built machines that played musical instruments with all the eloquence of a human player. His Automaton Flute Player, for example, was a life-sized wooden figure that could play twelve different melodies. Powered by three groups of three bellows, it had lips that opened and closed and moved backwards and forwards, and a movable tongue. Its seven levers, each encased in animal skin, simulated human fingers, giving the machine a human's soft touch.

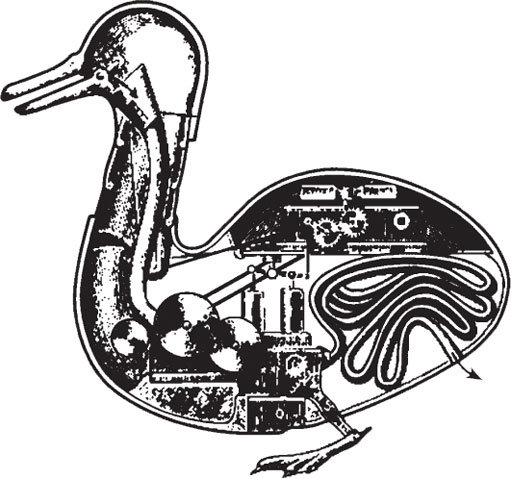

Most famous of all, however, was Vaucanson's Duck (Figure 2), a gold-plated copper automaton, which quacked and swam, rose on its legs and, astoundingly, ate food out of the exhibitor's hand, digested it and excreted it. Vaucanson devised an elaborate system of internal pipes to achieve this, complete with a chemical digestive plant in the place of the stomach. The duck made its last appearance in the Paris exhibition of 1844, long after Vaucanson's death in 1782.

Figure 2 Inside Vaucanson's Duck

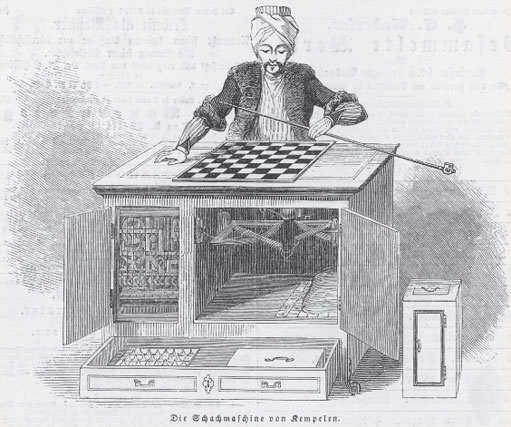

Figure 2 Inside Vaucanson's DuckGame-playing automata. Another favourite of the 18th and 19th century public were the machines apparently capable of playing board games, usually chess, against human opponents. The most famous of these, The Chess Automaton, better known as The Turk (Figure 3), was built by Baron Wolfgang Von Kempelen and toured Europe in the 1770s. The Turk was a wheeled wooden cabinet, with a chessboard and a life-sized wooden figure dressed in Turkish style mounted on its top. This machine offered to play chess against all comers, generally defeating them (its victims included Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin). As The Turk appeared to ponder, and then make, its move there would be an impressive mechanical clanking and a display of moving cogs. These, needless to say, had nothing to do with the machine's play: the cabinet concealed a human chess master. Such men had to be of small stature. Working by candlelight in conditions of appalling heat and cramp, playing the game and operating the mechanics of the robot arm, while covering up coughs and sneezes, not surprisingly many of them died early deaths from alcoholism or other illnesses. The chess genius and US Chess Champion, Harry Nelson Pillsbury, worked inside a later automaton, Ajeeb, for nearly ten years. He succumbed to syphilis in 1906 at the age of 34. Both The Turk and Ajeeb were eventually destroyed by fire.

Figure 3 The Turk

Figure 3 The TurkAll these contraptions were, of course, frauds. However, the 20th century has seen machines genuinely capable of beating human opponents at chess. In 1997, IBM's specialised computer Deep Blue beat the world chess champion Gary Kasparov in a six-game match. Since that epic struggle, Deep Blue's successors (Deep Junior, Deep Fritz and Hydra) have maintained a consistently good record against the highest-quality human opposition.

- Robots. Popular belief has it that the word 'robot' was coined by the Czech writer Karel Capek. In fact, the term was apparently invented by Capek's brother Josef; but the word did appear before the public for the first time in Karel Capek's 1920 play RUR: Rossum's Universal Robots. The literature of robots is immense, particularly in the 20th century, and there is no space to look at it here. The idea of machines in human form, stronger and maybe more intelligent than us, working with us as partners or slaves, seems to be endlessly fascinating.

Doubtless, you came up with several others.

Many of these contraptions might seem laughable – myths, dreams and deceptions of no relevance to a Computing course. But I think there are some serious points to be made here. These centre on three key questions:

- Why build such artificial entities?

- What sort of thing did people think these entities actually were?

- What has been the public attitude to the idea of artificial creatures?

Let's consider each of these questions in turn.