1.5 Design and needs

In the opening sections I raised the question of 'need' as a foundation for design activity. A dilemma came to light: although we might look for needs before generating design proposals, we recognise that some needs may only come to light as a result of getting involved in the generation and testing of various ideas. That is to say, although we attempt to specify our task, define the perimeters to our work, and impose guidelines for planning and direction, it is likely that in many situations we only really uncover detail about the needs when we become involved in designing. Many of the activities we might see in creative problem-solving in design, such as sketching, making models and prototypes and generating life-like computer images, actually have a very important role in problem-finding. Often the real problems can be uncovered only by generating models which provide feedback.

In some instances the feedback required is very particular. In the design of a gearbox, for example, the need might be explicitly stated and the models used in the generation and testing of the proposal can be quite abstract. They might exist only on computer and have no tangible form at all. On the other hand, the design of a new mobile phone might require extensive market testing using life-like models of several versions of the phone in order to elicit the impressions of the kind of people who might be future buyers of the product. Of course there will be many other types of models used to test other aspects of functionality. However, my point here is that vital information about the need might only emerge once a proposal has emerged. The phone manufacturer may find out that some designs do not convey the status expected: perhaps they are too big or too small; perhaps they just look wrong. The remedy might be straightforward, requiring only a few styling changes. Other user feedback might imply a more significant rethink of the whole project. There are two lessons here:

Designers have to formulate problems and needs as best they can at the outset of design activity, and yet sometimes they cannot completely define problems and needs before embarking on creative design activities.

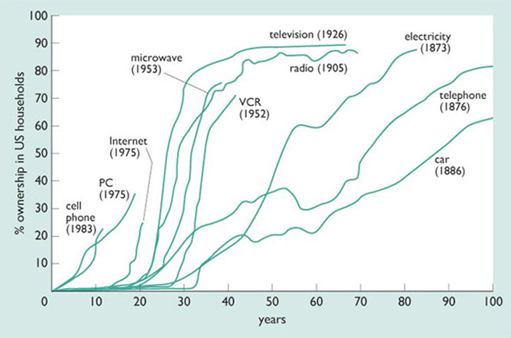

Designing means getting the correct type and quality of feedback at the correct time. It is vital that the types of models used at any particular stage in the design process be appropriate to the requirements of the design team. With pressures on manufacturers to reduce the time it takes for a new product to be developed and put on sale (Figure 8) then strategies for generating the appropriate feedback early in the design process are critical.

SAQ 3

If you were a professional designer needing to assess the performance, operation or appeal of the products listed below, what sort of models, physical or otherwise, might you use? (Hint: think about possibilities like scale drawings, mock-ups, computer simulations, etc.)

A new steel aerosol-spray can to re-market an existing deodorant.

A new family saloon car.

A swim suit.

An elevated section of road near to a town centre.

Answer

You might want to produce some images of what the new deodorant container might look like. This would provide general feedback about the visual qualities but if you required feedback on the feel and use of the steel package you would probably have to have full-size models made. Wooden models might be easiest to make but it would then be difficult to convey the cold feel of steel. There might also be the need to model the pressure inside the can, to ensure that the steel wall is thick enough.

Similarly with the car. If one only requires the initial impression of potential buyers then renderings or computer-generated images may be appropriate. Full size, highly realistic clay models are still used in the motor industry to facilitate feedback from potential users and for evaluation by the design team and senior management. If feedback on comfort is required then models using real seats, a dashboard, and a steering wheel might be used. Because such a model lacks the outer skin of the proposed car, it will look very different from the clay appearance-model.

The production of a swim suit is relatively low-cost. Some initial computer-based mapping of colours and textures onto a virtual human form may take place, but it is reasonable to make up a prototype and have it worn by a real person.

The elevated road is clearly too big and too complicated to model at full size. Even if you did make a full-sized model, what would it tell you? The information you actually require is likely to concern costs, material volumes, changes to traffic flow, changes to pollution etc. and these can be more successfully modelled via computer-based statistical techniques or specialist programs for civil engineering. You might also construct partial models to investigate, for example, the stress in a particular road section or support structure. A scale model of the design might be helpful in communicating the proposal to local residents. Increasingly, virtual reality can provide useful models for generating meaningful feedback about architecture and engineering.