1.1.2 Egyptian calculation

Box 1 A note on Egyptian scripts and numerals

The earliest Egyptian script was hieroglyphic, used from before 3000 BC until the early centuries AD. Initially an all-purpose script, it was eventually used only for monumental stone-carving and formal inscriptions. It had been superseded (by about 2000 BC) by a more fluid script called hieratic, used for more rapid writing on papyri. Later still, there developed a cursive, everyday script called demotic, that looks like a mad doctor's handwriting at the end of a bad day.

Most of the handful of extant mathematical papyri are written in hieratic. Because of the great variability of hieratic and demotic in the hands of different scribes, Egyptologists habitually transcribe all texts into the more legible and standardised hieroglyphic.

The representation of numerals in the different scripts shows an interesting development. Hieroglyphic numerals are formed on a straightforward decimal repetitive principle, each symbol for a power of ten being repeated as often as necessary. In hieratic, and even more so in demotic, new symbols were devised for each of two to nine, ten, twenty to ninety, and so on, so there was a great increase in the degree of cipherisation (having separate, concise, independent symbols for different numbers). Some historians have seen this as a significant step in the development of numeration.

Egyptian calculation was fundamentally additive. The most frequent operations were doubling (that is, adding a number to itself) and halving (that is, finding what number can be added to itself to make the number you started with). Here is a sample calculation for you to try (from the Rhind Papyrus problem 69); we start from the transcription into hieroglyphs so you can see the principles more readily.

Question 2

Given that in hieroglyphs | is 1, ![]() is 10,

is 10, ![]() is 100 and

is 100 and ![]() is 1000, transcribe this calculation into our numerals and try to work out what is being done, and how.

is 1000, transcribe this calculation into our numerals and try to work out what is being done, and how.

Discussion

The sum looks like a multiplication of eighty by fourteen; the scribe has considered the latter as ten and four, multiplied eighty by each (to give the lines marked by /) and added the results, to obtain 1120. Notice that to multiply 80 by 4, he first doubled SO and then doubled it again. Notice too, that multiplying by ten is very easy in hieroglyphs, simply by changing each symbol into the next one in the ordered sequence of symbols for powers of ten.

You can see from having tried this how it is possible to begin to make sense of Egyptian methods. Division turns out to be rather similar. The problem is seen in terms of discovering by what one number must be multiplied to make another. So, for instance, the calculation above could equally have stood for the division of 1120 by 80! One would scan down selected multiples of 80 to sec which would add up to 1120. This yields the answer 10 and 4 – that is, 14.

Of course, the answer to such an attempt at division may not always be exact if the calculation is restricted to whole numbers. Exploring what happens when a division does not yield a whole-number answer leads us to one of the most striking and influential features of Egyptian mathematics — their fractions.

Question 3

What has the scribe done to compute 19 divided by 8? (This is taken from Problem 24 of the Rhind Papyrus, transcribed into our numerals.)

Discussion

He is trying to find by what 8 must be multiplied to give 19. So he doubles 8, to give 16 which is 3 short of 19; so he must find what multiplies 8 to produce this remaining 3. He halves the 8 (obtaining 4, which is still too much), then halves that and halves it again. Notice that the quarter of 8 and the eighth of S together will make up the 3 he wants. So his answer, as indicated by the / marks, is the sum of 2 and 1/4 and 1/8.

This, for the Egyptian scribe, is the answer: 2 1/41/8. (Or, rather, the equivalent of that in hieratic.) One important thing to notice is that he did not, as we might do, add the fractions together to produce 23/8. In Egyptian mathematics, only what we would call unit fractions, that is, 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, and so on, are used, together with the fraction we would write as 2/3. Why there should have been what seems to us this strange restriction of Egyptian mathematics is an interesting question that we return to shortly.

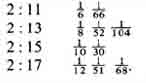

In view of the importance of the principle of doubling, as well as of the use of unit fractions, it was necessary to know what was the result of doubling fractions. Nearly a third of one side of the Rhind Papyrus (which is some 18 feet long by about 1 foot wide) is taken up with calculating the doubles of the odd fractions 1/3, 1/5, 1/7, …, 1/99, 1/101, expressed in the equivalent form of dividing 2 by the odd numbers from 3 to 101. We shall write these as 2 : 3, 2 : 5, and so on. For instance:

In modern notation, the first two results read:

We shall not pursue the details here of how these were calculated, but there is an example in Box 2 to illustrate the skill and ingenuity of Egyptian fraction-handling techniques.

Box 2 A note on how 2 : 17 was calculated

The instruction for this problem in the ancient Egyptian reads something like, ‘Get 2 by operating on 17’, which provides a clue to the guiding principle: do things to 17 until you arrive at 2.

The calculation is in two stages:

carry on halving 17 (starting from its two-thirds part) until some number under 2 is reached;

see what this leaves you with, to get back to 2 precisely.

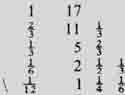

Step 1 of the calculation goes

Thus 1/12 will be part of the answer; what is the rest?

For step 2 the scribe wrote down the difference between the number reached (1 1/41/6) and 2.

Remainder 1/31/4

Question: How did the scribe know this?

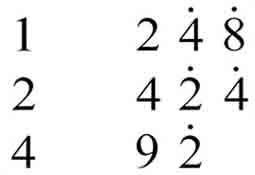

Then, as a subsidiary computation, the scribe worked out what needed to be done to 17 to get this remainder.

There seems to be a tight argument compressed into these figures; he has calculated that 3 times 17 is 51; and thus 1/51 times 17 is 1/3. Similarly 4 times 17 is 68; thus 1/68 of 17 is 1/4.

Since 1/31/4 is the remainder we needed, as parts of 17 these are 1/511/68.

The overall result, then is 2 : 17 = 1/121/511/68.

The one part of this calculation that is not explicitly written down is how the scribe arrived at the remainder, the difference between 2 and the number obtained at the end of the step (i) calculation, A method for doing this appears in other problems on the Rhind Papyrus, so we shall go through how it could have been done in this case.

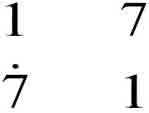

We had reached 1 1/41/6 and wanted to know how far short this was of 2. The method involves an auxiliary calculation, set up as follows. Express the fractions you have as multiples of some other convenient fraction, say 1/12. Then 1/4 is 3 times 1/12, and 1/6 is 2 times 1/12. The numbers 3 and 2 are written down (in red ink, on the papyrus, the rest being in black) and added: 5. Now, how far short of 12 are we? 7. So, the remainder we want is however many times 12 goes into 7:

So 1/31/4 is the remainder, as indeed the scribe wrote down.

Notice one thing, however, about the above results: what might seem to us the ‘obvious’ answer, for instance that 2 : 17 is 1/171/17, was never the one reached. The possibility of repeating the fraction in order to double it just did not count as an answer, it seems, for the Egyptian scribe. This observation gives us a clue concerning the question raised earlier above, of why in Egyptian mathematics we find only unit fractions (and 2/3).

The answer to this question is important and revealing, because thinking it through will inform us not only about Egyptian mathematics, but also about what studying history can involve. The question arose because it seemed to suggest itself from the source material, or from our efforts to understand it. We use fractions, the Egyptians also seemed to do so, yet only in a seemingly highly restricted way which drove them into subtle and complicated contrivances. Why did they not just use fractions as we do ? It would have saved them a lot of trouble! Now notice that the more the problem is spelled out, the more peculiar it begins to look. Imagine yourself asking the scribe, ‘Why do you only use unit fractions?’. His look of bewilderment will be explained if you go on to reflect that that question presupposes him to be making the deliberate choice of not using fractions in the way we do.

Expressed like that, it is surely an unreasonable presupposition. So how have we got into this problem, and how do we get out? The problem seems to have arisen partly conceptually and partly notationally. Conceptually, because the very use of the word fraction carries our set of expectations with it, whereas if we had used another word, such as reciprocal, say (for 1/7 can be thought of as ‘the reciprocal of 7’ as well as ‘one-seventh’), then no-one would have expected compound reciprocals. Notationally, the translation of the Egyptian symbol into ‘our’ fractions set up possibly unhelpful expectations. By looking again at the statement of Rhind Papyrus Problem 40 on the previous page, you will see that our ‘1/7’ was translating the hieroglyphic ![]() which in turn is equivalent to a hieratic squiggle with a dot on top. Translating these marks as

which in turn is equivalent to a hieratic squiggle with a dot on top. Translating these marks as ![]() , or by some people as

, or by some people as ![]() , helps preserve better the awareness that Egyptian fractions were conceptually different from ours.

, helps preserve better the awareness that Egyptian fractions were conceptually different from ours.

So the upshot of this argument is that our initial question, of why Egyptian fractional usage was ‘restricted’ to unit fractions, was badly posed. It need not arise if we reconsider the question as: what was the Egyptian concept for which we have hitherto used the word fraction? The Egyptian symbol for what we have been thinking of as 1/3, 1/4,… is better translated by the word part, as in the third part, the fourth part, and so on. The reason this is better is that to say one seventh or use the symbol 1/7 (say) invites the idea familiar to us of there being ‘two sevenths’ (2/7), ‘three sevenths’ (3/7) and so on, whereas the seventh part is unique. So this would explain why the result of doubling the eleventh part is not the eleventh and the eleventh; for there can be only one eleventh part. Or, to put it another way, to write 2 : 17 as 1/171/17 would simply be a restatement of the problem, not an answer to it.

The Egyptian concept of part is explained more fully in the box below.

Box 3 Sir Alan Gardiner on the Egyptian concept of part

The commonest method of expressing fractions in Egyptian was by the use of the word ![]() r ‘part’, below which (or partly below it in the case of the higher numbers) was written the number described in English as the denominator. Thus

r ‘part’, below which (or partly below it in the case of the higher numbers) was written the number described in English as the denominator. Thus ![]() , r-5 ‘part 5’ is equivalent to our 1/5,

, r-5 ‘part 5’ is equivalent to our 1/5, ![]() r-276 ‘part 276’ to our 1/276.

r-276 ‘part 276’ to our 1/276.

For the Egyptian the number following the word r had ordinal meaning; ![]() r-5 means ‘part 5’, i.e. ‘the fifth part’ which concludes a row of equal parts together constituting a single set of five. As being the part which completed the row into one series of the number indicated, the Egyptian r-fraction was necessarily a fraction with, as we should say, unity as the numerator. To the Egyptian mind it would have seemed nonsense and self-contradictory to write r-7 4 or the like for 4/7; in any series of seven, only one part could be the seventh, namely that which occupied the seventh place in the row of seven equal parts laid out for inspection. Nor would it have helped matters from the Egyptian point of view to have written

r-5 means ‘part 5’, i.e. ‘the fifth part’ which concludes a row of equal parts together constituting a single set of five. As being the part which completed the row into one series of the number indicated, the Egyptian r-fraction was necessarily a fraction with, as we should say, unity as the numerator. To the Egyptian mind it would have seemed nonsense and self-contradictory to write r-7 4 or the like for 4/7; in any series of seven, only one part could be the seventh, namely that which occupied the seventh place in the row of seven equal parts laid out for inspection. Nor would it have helped matters from the Egyptian point of view to have written ![]() r-7( + )r-7( + )r-7( + )r-7, a writing which would likewise have assumed that there could be more than one actual ‘seventh’. Consequently, the Egyptian was reduced to expressing (e.g.) 4/7 by 1/2( + )1/14 For more complex fractions even as many as five terms, all representing fractions with 1 as the numerator and with increasing denominators, might be needed; thus the Rhind mathematical papyrus, dating from the Hyksos period, gives as equivalent of our 2/61 the following complex writing:

r-7( + )r-7( + )r-7( + )r-7, a writing which would likewise have assumed that there could be more than one actual ‘seventh’. Consequently, the Egyptian was reduced to expressing (e.g.) 4/7 by 1/2( + )1/14 For more complex fractions even as many as five terms, all representing fractions with 1 as the numerator and with increasing denominators, might be needed; thus the Rhind mathematical papyrus, dating from the Hyksos period, gives as equivalent of our 2/61 the following complex writing: ![]() r-40 r-244 r-488 r-610 ‘1/40 + 1/244 + 1/488 + 1/610’. It is generally known that the same cumbrous methods of expression were in common use with the Greeks and Romans. It would seem also that a relic of them survives in the use of English ordinals in the names of our fractions, though we speak of ‘one-third’ and ‘three-fifths’ without any qualms. […]

r-40 r-244 r-488 r-610 ‘1/40 + 1/244 + 1/488 + 1/610’. It is generally known that the same cumbrous methods of expression were in common use with the Greeks and Romans. It would seem also that a relic of them survives in the use of English ordinals in the names of our fractions, though we speak of ‘one-third’ and ‘three-fifths’ without any qualms. […]

Though the Egyptians were unable to say ‘three-sevenths’ or ‘nine-sixteenths’, yet they made a restricted use of certain fractions which appear, at first sight, to stand on the same footing: a great rôle is played in Egyptian arithmetic by the fraction ![]() rwy 'the two parts’ (out of three), i.e. 2/3, and a very rare sign

rwy 'the two parts’ (out of three), i.e. 2/3, and a very rare sign ![]() r-3 (perhaps to be read

r-3 (perhaps to be read ![]() mt rw) can be quoted for ‘the three parts’ (out of four), i.e. 3/4. These ‘complementary fractions’ represent the parts remaining over when ‘the third’ or ‘the fourth’ is taken away from a set of three or four, and indeed their existence is practically postulated by the terms r-3, r-4. But we must be careful to note that in r-3=3/4 the numeral is a cardinal, not an ordinal, and that the expression means ‘the three parts’ and was not construed, as with ourselves, as meaning ‘three fourths’. In ordinary arithmetic the only complementary fraction used was 2/3. Compare in English ‘two parts full’, i.e. two-thirds full, doubtless a survival of the old Egyptian way of regarding the same fraction.

mt rw) can be quoted for ‘the three parts’ (out of four), i.e. 3/4. These ‘complementary fractions’ represent the parts remaining over when ‘the third’ or ‘the fourth’ is taken away from a set of three or four, and indeed their existence is practically postulated by the terms r-3, r-4. But we must be careful to note that in r-3=3/4 the numeral is a cardinal, not an ordinal, and that the expression means ‘the three parts’ and was not construed, as with ourselves, as meaning ‘three fourths’. In ordinary arithmetic the only complementary fraction used was 2/3. Compare in English ‘two parts full’, i.e. two-thirds full, doubtless a survival of the old Egyptian way of regarding the same fraction.

Thus equipped, we can more easily see how a calculational practice involving parts could form a coherent framework in itself, not needing the overtones of our concept of fractions. That it was a coherent framework is attested by its extraordinary longevity. Two millennia after the Rhind Papyrus, for instance, we find many of the results in Ptolemy's Almagest (c. AD 150), the greatest of Greek astronomical texts, presented in Egyptian fashion, as in this passage.

One [sighting] we made in the year 18 of Hadrian, Egyptianwise Pharmouthi 2–3, according to which the morning Venus was at its greatest elongation from the sun; and, sighted with the star called Antares, it was 11 + 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/12° within the Goat, while the mean sun was then 251/2° within the Water Bearer. And so the greatest morning elongation was 43 +1/2 + 1/12°.

Ptolemy, Almagest Book X, ch.3, translated by R. Catesby Taliaferro. The ‘plus’ signs have been inserted by the translator.

Indeed the use of parts can still be found in European writers of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries AD. Henceforth, we shall use ![]() for 1/7, and similarly for other parts.

for 1/7, and similarly for other parts.

Having absorbed, then, the idea that past mathematical procedures and concepts may actually be more difficult to understand unless we do our best to meet them on their own terms, let us turn back to Egyptian calculation methods. Here is an example of a procedure that was followed to solve a problem. We have chosen Rhind Papyrus Problem 24, as you have already studied one calculation from it (Question 3).

The problem is in Extract 1, so please study the extract briefly now before coming back to the offered explanation which follows.

The numbering of the problems, by the way, is that of a nineteenth-century German editor of the Rhind Papyrus — in the original, the problems are unnumbered.

The problem, ‘A quantity, 1/7 of it added to it, becomes it: 19’, can be seen to mean something like, ‘A quantity and the seventh part of it is nineteen. What is the quantity?’. The way this is solved is that the scribe produces the number 7, as a kind of trial guess perhaps, but one having the useful property that its seventh part is easy to determine:

So we can see that had the quantity been seven, it and its seventh part would make 8; but what we want is for it and its seventh part to make 19; so if we knew how many times 8 goes into 19, we would know how many times 7 goes into the quantity we want. This part of the calculation, dividing 19 by 8, is what you did in Question 3, and the answer was 2 ![]()

![]() . So all that remains is to multiply that by 7 to get the answer, which is done by doubling.

. So all that remains is to multiply that by 7 to get the answer, which is done by doubling.

The sum of these is 16 ![]()

![]() , which is therefore the desired quantity. But just to make sure, the scribe checks the result — ‘The doing as it occurs’. He adds to the quantity its seventh part (2

, which is therefore the desired quantity. But just to make sure, the scribe checks the result — ‘The doing as it occurs’. He adds to the quantity its seventh part (2 ![]()

![]() ), to show that their sum is indeed 19 as required.

), to show that their sum is indeed 19 as required.

The strategy followed in this problem, namely choosing any convenient number and working out the solution in respect to it, then multiplying by the ratio of your answer to the answer you want, is quite a common one in Egyptian mathematics. Indeed, if we generalise this description of the strategy, and call it a systematic method of'trial and error’, then this seems characteristic of the Egyptian style of arithmetic. For example, if you look again at the way division was described (Question 3, Comment) you will notice that it can be seen in terms of getting close to the desired result and then seeing what needs to be done to make up the remainder. The strategy used in Problem 24 is a solution method in common use up to quite recent times, appearing under various names such as the method of false position or the rule of false.

We now return to Problem 40, with which we started. It provides another example of this strategy.

Question 4

Re-read the suggested explanation of what Problem 40 is about, which was given in the paragraph after Question 1, and see if you can work out how the scribe has solved it, in the way that we approached Problem 24. Use the English translation in Extract 1 to work from (unless your hieratic or hieroglyphic skills are especially well developed). It will save you time if you have two further pieces of information: ![]() is the symbol we use to denote 2/3, and the scribe makes a guess or assumption about how many loaves the man who gets least receives, as well as about what the constant difference is.

is the symbol we use to denote 2/3, and the scribe makes a guess or assumption about how many loaves the man who gets least receives, as well as about what the constant difference is.

(Do not spend any longer on this than you feel you want to — go on to read the Comment when you are ready.)

Discussion

The scribe produces for the initial try a share difference of 51/2, and the assumption that the last man receives 1 loaf. So the previous man got 61/2, the one before him 12, then 171/2, then 23. (This comes from adding 51/2 each time.) Adding all of these together gives 60, so since it was actually 100 loaves to start with, another 40 (that is, the two-thirds part of 60) is needed. He says ‘Make thou the multiplication: 12/3’ and multiplies up each of his initial shares 23, 171/2, 12, 61/2 and 1 by 12/3, and finally checks that they do indeed total 100 by adding the results.

That is what appears on the papyrus. But in checking over what the scribe has done, and comparing it with the statement of the problem, it becomes clear that a substantive part of the solution has taken place off-stage, as it were. The shares do have the property they ought to, namely that the sum of the least two is one seventh of the sum of the largest three. But this is not something he shows, nor does he indicate how the initial ‘guesses’ were arrived at to ensure this. (Nor, indeed, does he explicitly give the answer to the question, ‘What is the difference of share?’.) We might conjecture that either something was left out during his copying the solution (at the start of the Rhind Papyrus the scribe says he is copying an earlier one), or else perhaps that it was only this application of the false position strategy he wanted lo show.

This discussion has raised the question of who or what the Rhind Papyrus was for, that is, what the scribe's intention was. His opening words were, in Chace's free translation, ‘Accurate reckoning. The entrance into the knowledge of all existing things and all obscure secrets’, which is interesting, but does not really clarify for us whether this kind of thing was taught to schoolchildren, or whether the Rhind Papyrus represented quite an advanced theoretical work by Egyptian standards. In trying to understand this ancient mathematical activity, it is natural for us to ask how it compares with later mathematics. It would be interesting to know whether it were simply a collection of empirical computational techniques, brought together for applying to everyday practical problems, or whether there are visible traces of, say, the more abstract theoretical tone that you will be seeing in Greek mathematics. Historians have differed in the judgements they have reached on this question. For instance:

The Rhind and Moscow papyri are handbooks for the scribe, giving model examples of how to do things which were a part of his everyday tasks.… The sheer difficulties of calculation with such a crude numeral system and primitive methods effectively prevented any advance or interest in developing the science for its own sake. It served the needs of everyday life …., and that was enough.

G. J. Toomer.

A careful study of the Rhind Papyrus convinced me several years ago that this work is not a mere selection of practical problems especially useful to determine land values, and that the Egyptians were not a nation of shopkeepers, interested only in that which they could use. Rather I believe that they studied mathematics and other subjects for their own sakes.

A. B. Chace.

Question 5

Which of these views do you feel more applicable to what you have seen of the Rhind Papyrus (namely, Problems 24 and 40)?

Discussion

There is something to be said for Toomer's view: the problem of dividing loaves among a group of men could certainly have been an everyday task for the overseers of large building works, for instance; and your experience of Egyptian calculation may well have inclined you to the view that ‘crude’ and ‘primitive’ are understandable epithets.

But there are features of the problems which are harder to fit with everyday life in quite so straightforward a way. For instance, the circumstances under which real loaves are to be divided among a group of people in arithmetical progression are hard to imagine. Again, the fact that Problem 24 is posed in terms of'a quantity’ (the Egyptian word can also be translated as 'heap' – something rather unspecific) does imply a certain level of abstraction, a recognition that the same techniques and rules apply to any of a range of real-world objects. So there is some recognisable mathematical activity ‘for its own sake’, which was Chace's claim.

However, this does not quite resolve the matter. If the Rhind Papyrus were primarily a teaching document, and if it were the calculation methods that one wanted to teach, then the fact that Problem 40 is quite unrealistic may be a tribute to the scribe's imaginative teaching style as much as to an exploration of mathematics for its own sake. Quite what significance should be attached to the formulation of Problem 24 is problematical. Some historians have seen in this an early technique foreshadowing the later development of algebra, insofar as that is concerned with operating on unknown quantities. On the other hand, the level of abstraction in this problem could be seen as no greater than that implicit in the very use of numbers. That one can have things-numbers-that apply indifferently to a range of real-world objects is quite a sophisticated concept, but one reached long before the Egyptian records to which we have access.

Let us reflect on the situation where historians reach apparently contradictory views. How is this possible, and how do we decide which, if any, we agree with? Question 5 implied a response to the latter question, that it is immediately helpful to check out the judgements against whatever relevant source material you are aware of. We did not reach any very firm conclusion, though, either because we have not yet looked at enough evidence, or perhaps because moving from the evidence to a judgement upon that evidence is more difficult than appears at first sight. So we should go on to investigate more fully what evidence, and what arguments from that evidence, these historians used to reach their conclusions. (Note that what we are doing at present has more general import. Our interest is not only in the pros and cons of this particular question, bul also in trying to work towards a method which can apply in other contexts in order to evaluate historical judgement.) The fuller passages from which the above views of Chace and Toomer are taken are dealt with on the next page. You will also learn more about the contents of the Rhind Papyrus from these extracts.