3.1 The shape of the martian surface

You learned in the introduction about the early efforts to map the surface of Mars and the tantalising suggestions of the presence of water based on the features seen on the planet’s surface. This approach, of studying the planet’s geomorphology (surface features), is still key to finding water on Mars. On Earth, rivers, lakes and ice carve out characteristic shapes in the landscape by erosion. These shapes can be used to identify where water might have once been.

Key indicators that water has been present include:

- vast river networks of deep valleys and channels

- large lake basins and channels caused by floods

- rounded pebbles found in dry riverbeds, indicating the flow of water was strong enough to tumble and round the pebbles over time.

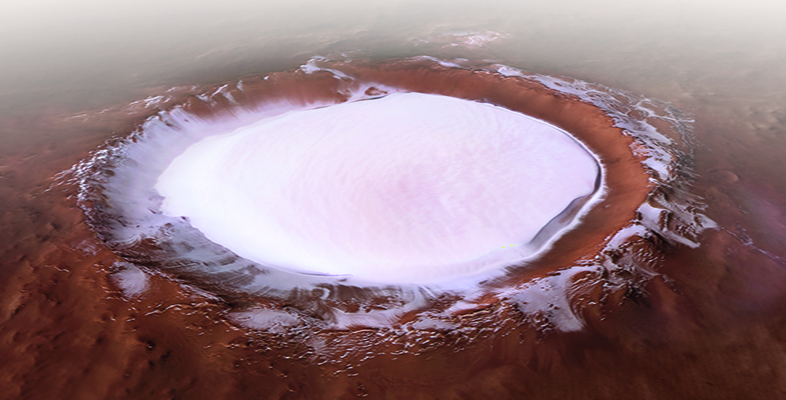

Mars’ surface also shows evidence of circular features called craters, formed when an object from space has impacted on the martian surface, ejecting material. Although they don’t indicate the presence of water, they do help to determine the relative timing of events in Mars’ history. On Earth, some ancient craters show evidence that the energy generated on impact resulted in the heating of groundwater, generating hydrothermal systems that could have been habitable places where life may flourish.

These features can all be identified from images taken of the martian surface by orbiting spacecraft, which you will hear about shortly. However, what if those features are no longer visible on the surface because they occurred much further back in Mars’ history?

For this, it’s important to look in the martian geological record. Evidence for water in the past (on Earth or Mars) is recorded in rocks in several different ways.

Water can carry rocks of many different sizes and shapes, and then deposit these in beds, one on top of another. Sometimes these beds show a repeating pattern, suggesting seasonal fluctuations. Sometimes the beds are inclined against one another, known as cross bedding. Water can also erode existing beds so they might appear to be truncated – this break is known as a discontinuity. Rocks that show these features include some sandstones and mudstones, most of which form in flowing water or large bodies of water. However, water also evaporates, and when it does it can deposit minerals such as clay minerals or salts.

To find details such as these on the martian surface requires much higher resolution images than those available on orbiting spacecraft, which typically cannot resolve anything below 20 cm in size. For this, cameras on landers and rovers are important, for example the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) on NASA’s Curiosity rover is able to resolve features less than a millimetre in size. However, identifying the presence of minerals requires more sophisticated techniques, as you will learn now.