4.4 The 1990s revival

1997 was a big year for Mars exploration. NASA’s orbiter, Mars Global Surveyor, reached the planet and the Pathfinder lander, with its shoebox-sized Sojourner rover, arrived on the martian surface.

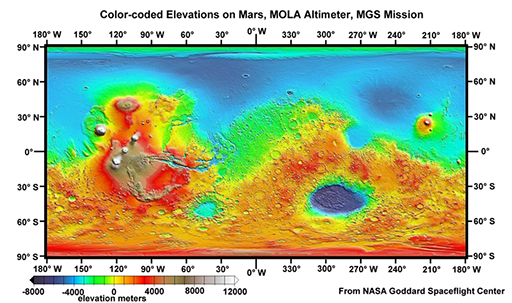

Mars Global Surveyor was equipped with instruments including a high-resolution camera (that captured images of what appeared to be gullies formed by flowing water) and a laser altimeter (to measure the shape and elevation of the surface in detail) (Figure 21). This topographical information has revolutionised our understanding of Mars’ geomorphology, and provided essential information for engineers designing spacecraft for missions to Mars.

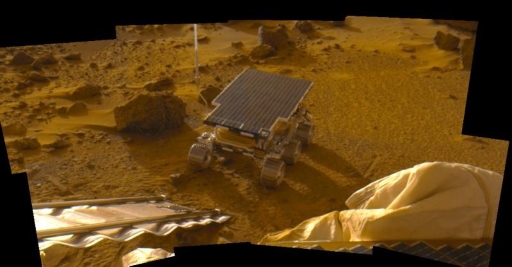

Despite the successes of Mars Global Surveyor, in the search for water at that time, the Pathfinder mission took centre stage. This was mainly because it carried the first martian rover – the Sojourner rover (Figure 22). Sojourner did not directly contribute to the investigation of water on Mars but was an important demonstrator of instruments that would be used on Mars in the future. The Pathfinder lander, however, made a number of important discoveries.

Pathfinder was fitted with an instrument with which to measure temperature variations at its landing site, Ares Vallis. Although it observed early morning water ice clouds in the lower atmosphere, even the warmest temperature it recorded was −8 °C, seemingly too cold for pure liquid water to exist on the surface. Two other clues, however, suggested this had not always been the case. Firstly, it detected that airborne dust was magnetic. This was speculated as being because it contained the mineral maghemite, a magnetic iron oxide. Importantly, maghemite forms from the weathering of iron in rocks.

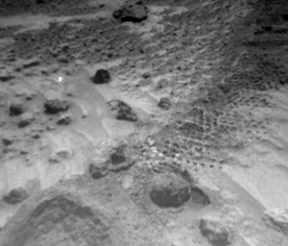

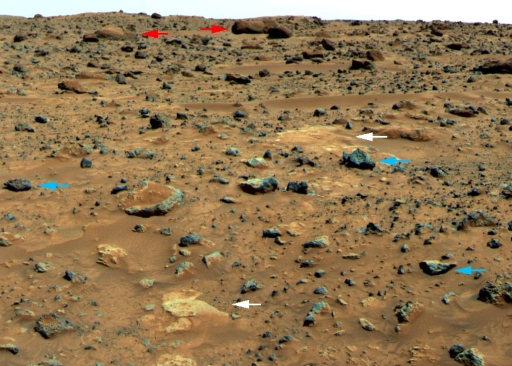

Secondly, you will see when looking at Figure 23, taken at the landing site that Pathfinder also found evidence of flowing water in Mars’ past. This evidence included rounded rocks (labelled with red arrows) that were likely to have been shaped by the forces of water, possibly during a flood. The pale areas on Figure 23, indicated by the white arrows, are also believed to be deposits left behind by evaporating water, or aggregates of material fused together by the action of water. In contrast, the blue arrows indicate rocks with sharp edges that were probably ejected by nearby impact craters and/or ancient volcanoes.

Although the presence of rounded pebbles (which you can see more closely in Figure 24) is good evidence that there was once water, the pebbles were found buried in loose sand, making it hard to clearly discern their relationships to each other. It was therefore not possible to absolutely confirm a watery origin and the search for compelling evidence of liquid water continued!