4 Violence within armed conflicts

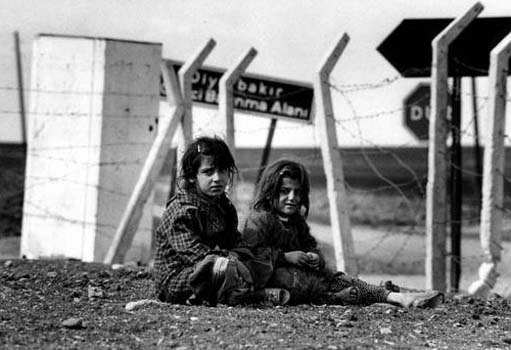

4.1 The effects of armed conflict on children

The final area of violence examined in this course involves children caught up in armed conflict, as victims, perpetrators or witnesses in violence affecting whole communities. It is important to emphasize that the three sites of conflict discussed in this course – family, schools and the community – are in no way exclusive. It is also important to stress that, in some parts of the world, criminal violence and repressive law enforcement measures (including harsh prison regimes) affect children's daily experiences of violence. Furthermore, gun violence against children is not limited to armed conflict. In some cities in the USA, children are as likely to be affected by violent death from guns as children living in a war zone. Psychologist James Garbarino refers to these as ‘war-zone neighbourhoods’, where

almost every fourteen-year-old has been to the funeral of a playmate who was killed, where two-thirds of the kids have witnessed a shooting, and where young children play a game they call ‘funeral’ with the toy blocks in their preschool classroom.

(Garbarino, 1999, pp. 17–18)

This section, however, will concentrate on the effects of armed conflict on children. These go far beyond injury and death to children and cause suffering to many children who are not directly involved. For example, during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, researchers found that children living in Kuwait suffered from anxiety and sleeplessness, loss of appetite, unexplained crying, bed wetting and unexplained physical symptoms such as headaches and stomach problems, even when they had not directly witnessed acts of violence. There were also rises in social problems such as truancy, poor academic performance and verbal and physical conflicts with teachers and other adults (King, 1999). At the end of the Gulf War, concern shifted away from Kuwaiti and on to Iraqi children, both those in the Kurdish and Shia communities of Iraq, who opposed Saddam Hussein and suffered persecution from state sources, and those who suffered as a result of the lack of food and medical care in the country, caused by the embargo on Iraq. These children too may be seen as casualties of war.