4.2 Violence within communities

Click here [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] to view Reading B

Reading

The long-standing conflict in Northern Ireland had many repercussions for children. The effects of the terrorist and counter-terrorist activities have been extensively studied by Ed Cairns, who, in Reading B (above), looks at how violence affected children during the 1970s and 1980s. This reading was published in 1987, and consequently provides an account of Northern Ireland at a particular time in history. Although the situation is different today, the reading gives a good sense of how children experience the everyday effects of living in a civil conflict. It also emphasizes that, even in a modern, wealthy society such as the UK, war affects children's lives. As you read through it, note the various forms of violence that children suffer, both physical and emotional.

Discussion

In this extract, Cairns looks at both the physical and the psychological effects of war on children. The majority of children in Northern Ireland may not have been subjected to actual physical assault or have witnessed it directly, but Cairns points to the stress and difficulties many children faced under these circumstances. Many families were forced to move when they experienced violence because of their religion or their organizational affiliation. War, even a ‘low level’ conflict such as Northern Ireland, disrupts the daily patterns of people's lives, making children's families and homes part of the conflict.

The Good Friday Agreement of 1999 was supposed to bring a formal end to much of the terrorist violence in Northern Ireland. However, several people have been killed since and sectarianism remains entrenched. Other social problems have also become more visible in Northern Ireland since 1999. Crime has risen, drugs have become more widely available and young people have continued to be caught up in violence. Older youths are subject to arbitrary justice from paramilitary squads who threaten and carry out beatings or knee-cappings as punishment for a range of antisocial offences such as joyriding and taking or supplying drugs. Many of the victims of these are young men under eighteen. In 1999–2000, 47 youths under eighteen were punished by Republican and Loyalist paramilitary groups, compared with 25 in 1997–98 (BBC Online, 2001). These groups claim to keep law and order in their respective communities, believing that these young people deserve their punishment and that, through such acts, order is kept. In other instances, being from the wrong part of the community in the wrong place is enough to be beaten up. Neville, aged seventeen, expresses this feeling of insecurity well.

They just want to know if you're a Protestant or a Catholic. And if you're in the wrong area, like, that's you hammered. You might as well book your hospital place now.

(Thomson, 2002, p. 16)

Once again, in a situation such as Northern Ireland, children cannot be labelled simply as the victims of violence. Some children have also been perpetrators, throwing stones at soldiers or calling abuse. Some were simply passive witnesses to violence, while others were more active colluders. Some have been very politicized, seeing the conflict as a struggle of ideologies, others were socialized into violence by their families or their communities at a very young age. As Ciaran, aged seventeen, told researchers about his own induction into violence.

Time I was sent out, by the father, out to the police, wi' bottle – to throw at them. I was only five or six. I knew, well I knew it was wrong but I thought it was right because that's what I was taught to do.

(Thomson, 2002, p. 16)

Activity 4 Children's induction into violence

Read the quotation below and make notes on the questions that follow it.

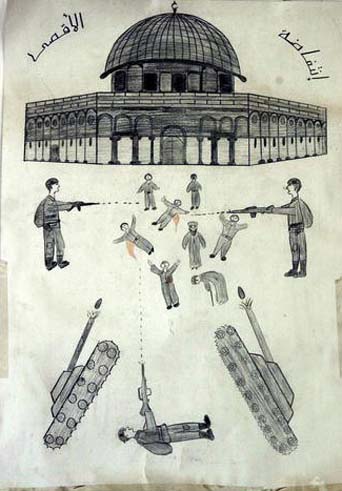

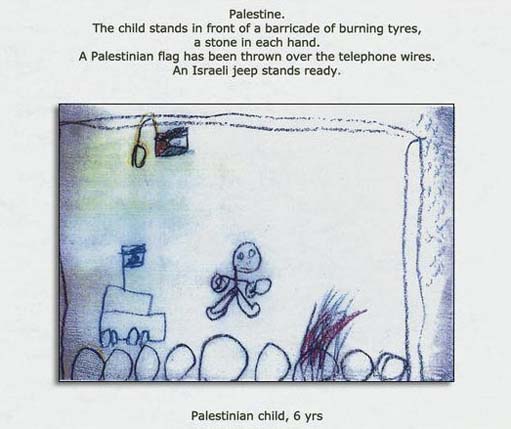

In Palestine rioting and stone throwing brought the local children to the attention of the world's media. However, far from being a childish behaviour … stone throwing amongst children in Palestine has been elevated to a military art with specific roles assigned to children of different ages. Those aged 7–10 years are given the job of rolling tyres into the middle of the road. These tyres are then set alight in order to disrupt traffic and attract Israeli soldiers. The next youngest age group (11–14 years) use slingshots to attack passing cars. These two groups are used to prepare the ground for … the ‘veteran stone throwers’. These young people use large rocks and inflict the worst damage on passing traffic and hence ‘they are the most sought after by the Israelis’. This command structure is coordinated by older youths who from the vantage points they occupy determine which cars to attack for example, or when to retreat when the soldiers advance.

(Cairns, 1996, pp. 112–13)

Do you see throwing stones at soldiers as ‘childish’ behaviour or is it an example of political violence among children?

Are these Palestinian children victims of violence or perpetrators of it? Should this affect the ways the Israelis treat them?

Discussion

These children have been raised in an atmosphere of violence and, to them, the Israelis are the enemy. They have suffered both direct violence in the form of family members killed or arrested and indirect violence in the form of prolonged curfews. Given this, it seems naive to dismiss their stone throwing as childish behaviour. The Israeli government, like the UK government, has found it very difficult to know how to react to young boys throwing stones at its soldiers. It is hard to know how politically aware and astute these children are, and therefore how knowingly violent, or whether they have been persuaded to take part by peer pressure or the chance to join in a group activity. It depends largely on your perception of children. If you believe that children are innocent, both of bad intent and of ideological motivation, then stone throwing is simply game playing. If, however, you believe that it is possible for children to be politically motivated and committed to a cause, then young people throwing stones are taking part in political violence.

There may also be another explanation for throwing stones at soldiers. In the absence of anything else to do, it may occur due to boredom. The children in Gaza and the West Bank have to cope with long curfews, while children in Northern Ireland also express a sense of frustration about their situation and their inability to change it.

Like something when we throw [things] cos you've nothing to do – the streets are boring … most of the tax money goes on helicopters and paying police. The money could be going on parks and theatres and football grounds and all that there. [I prefer] police out, parks, and all that stuff in.

(Luke, fourteen, quoted in Thomson, 2002, p. 16)

Children who are pictured throwing stones or rioting raise further questions about manipulation, not only by adults within their communities but also by the national and international media. Children may be encouraged to act up for the cameras or their political ideals may not be discussed, leaving their actions uncontexualized. The political beliefs of those who view the images will also alter how these children are seen – whether as nascent terrorists, freedom fighters or vulnerable children playing at war.