Discovering disorder: young people and delinquency

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 2:10 AM

Discovering disorder: young people and delinquency

Introduction

This course will introduce two approaches to understanding juvenile delinquency. The psychological approach focuses on examining what makes some individuals, but not others, behave badly. The sociological approaches looks at why some individuals and some behaviours, but not others, are defined as disorderly. Much of this course is based on the chapter ‘Discovering disorder: young people and delinquency’ by Catriona Havard and John Clarke (2014).

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course DD102 Introducing the social sciences.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

compare and contrast two different approaches to studying juvenile delinquency

understand psychological approaches to studying juvenile delinquency such as Eysenck’s personality theory and the Cambridge Study of Delinquent Development behaviour which focus on explaining why some individuals commit crimes yet others do not

understand sociological approaches to studying juvenile delinquency, such as those by Howard Becker, Stanley Cohen, and Stuart Hall and his colleagues, which focus on explaining why some individuals and some behaviours are labelled as deviant while others are not.

1 Discovering disorder: young people and delinquency

The problems of social order and disorder appear in many forms – from rudeness to violence; from bullying to civil war. The history of the UK is full of threats and dire warnings that the social order is breaking down – from people stealing the king’s firewood to internet abuse. Order appears to be haunted by the threat of disorder.

In this course, we are going to examine one very visible aspect of the relationship between order and disorder by exploring how social scientists have addressed disorderly behaviour by young people. Of course, social scientists’ interest in youthful misbehaviour reflects anxieties and concerns of the wider society, which as the quotations in Activity 1 suggest, is a recurring concern.

Activity 1

As you read the quotations below, can you tell when and where they were written?

Socrates, the Athenian philosopher, writing around 400 BC

The young people of today … have bad manners, they scoff at authority and lack respect for their elders. Children nowadays are real tyrants … they contradict their parents … they tyrannise their teachers

The Daily Post on 29 May 2013

Yobs destroy children’s scarecrows in ‘mindless wrecking rampage’

Sir Keith Joseph Member of Parliament (MP) in 1977

For the first time since … Robert Peel set up the Metropolitan police, areas of our cities are becoming unsafe for peaceful citizens by night, and some even by day

The Daily Graphic, 25 August 1898

A gang of roughs, who were parading along the roadway, shouting obscene language … and pushing respectable people down

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 4 items in each list.

Socrates, the Athenian philosopher, writing around 400 BC

The Daily Post on 29 May 2013

Sir Keith Joseph Member of Parliament (MP) in 1977

The Daily Graphic, 25 August 1898

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Yobs destroy children’s scarecrows in ‘mindless wrecking rampage’

b.The young people of today … have bad manners, they scoff at authority and lack respect for their elders. Children nowadays are real tyrants … they contradict their parents … they tyrannise their teachers

c.A gang of roughs, who were parading along the roadway, shouting obscene language … and pushing respectable people down

d.For the first time since … Robert Peel set up the Metropolitan police, areas of our cities are becoming unsafe for peaceful citizens by night, and some even by day

- 1 = b,

- 2 = a,

- 3 = d,

- 4 = c

Discussion

The first quotation is usually attributed to Socrates, the Athenian philosopher writing around 400 BC. The second quotation is contemporary, from the Daily Post on 29 May 2013 (Williams, 2013). The third quotation is from Sir Keith Joseph Member of Parliament (MP) in 1977 and the fourth quotation is from The Daily Graphic, 25 August 1898 (both are quoted in Pearson, 1983, pp. 4–5). Together they suggest that some of the same concerns about youthful behaviour are evident from the time of the Ancient Greeks to today.

1.1 Crime and deviance

Social scientists study many forms of criminal and deviant behaviour: criminal behaviour is behaviour that breaks the criminal laws of the country; deviant behaviour may include crimes, but refers more widely to those behaviours that break established social expectations or norms.

Activity 2

Can you think of any criminal behaviours that are not deviant? Can you think of any deviant behaviours that are not crimes? Write your thoughts in the box below.

Discussion

We can think of a number of criminal behaviours that are not seen as deviant. For example, much white-collar crime (in businesses and offices) has long been viewed as normal, and rarely results in prosecution. Such crimes may range from stealing office stationery (often viewed as a ‘“perk” of the job’) or ‘fiddling expenses’ through financial fraud to acts of organisational neglect, omission and carelessness that result in deaths or injuries to workers and/or customers (for examples, see Slapper, 2009; Tombs and Whyte, 2010).

There are also many forms of deviant behaviour that are not crimes (that is, offences that can be prosecuted under the current criminal law). For example, a variety of behaviours that are called ‘disorders’ (eating disorders, psychological disorders such as hyperactivity) are deviant without being criminal. But it is important to remember that this is not a clear-cut distinction. Laws change over time and vary between countries, so that what may be a crime in one place or at one time may not be so at another. But it is also the case that whether some behaviour gets treated as a crime or even viewed as deviant may depend on more contextual factors: Who did it? Where did they do it? We will come back to these problems later in the course.

For social scientists, both crime and deviance can be viewed as forms of social disorder. However, there is a very strong focus of attention on juvenile or youthful misbehaviour: often referred to as juvenile delinquency. At the core of this is criminal behaviour (behaviour that breaks the current laws of the country), but juvenile delinquency also includes what might be called status offences (behaviour that is illegal only for this particular age group such as under-age smoking or drinking, or truanting from school). However, juvenile delinquency may involve behaviour that is judged to be deviant (breaking social norms or expectations) such as young people ‘hanging about’ on street corners, or congregating in loud or aggressive groups. In these ways, ‘juvenile delinquency’ is far from being a clear or simple concept, and it is important to keep this in mind as you read further.

In this course, we are going to follow this focus on disorderly behaviour by young people. We will trace two main lines of approach within the study of youthful misbehaviour:

- The first of these focuses on the search for the causes of delinquency: what makes young people (or some young people) behave badly? This is probably where you would expect most of the effort of social scientists to be expended – isn’t explaining why things happen or why people behave as they do the business of the social sciences?

- The second part of the course takes a different – and perhaps less expected – approach to studying delinquency. Here, the focus is on the processes and agencies of control, starting from rather different questions: not, why did this person do X, but why is this behaviour viewed as delinquent? Why do these people get arrested for it? Why is that group of people or that behaviour ignored or treated as normal?

Both approaches are centrally concerned with disorder, but take very different routes to understanding it. We hope that by the end of this course you will have a good appreciation of what each approach has to offer and why the differences between them are significant.

2 Studying the causes of juvenile delinquency

Social scientists have used a number of approaches to try and explain why young people misbehave. Some researchers have focused on the individual’s personality, while other researchers have looked at different factors that might influence individuals to commit crime, such as their family background. The theories that focus on why some individuals may be more likely than others to commit crimes are called micro theories. Approaches that examine the immediate family or social context are called meso-level theories, while those that examine larger social or structural conditions are called macro-level theories. The social sciences often distinguish between these different levels of analysing things.

The following sections will focus on the work of psychologists who developed theories to try and understand why some people behave in deviant ways, and even commit crimes, as compared to those who do not. Sections 2.1 to 2.3 look at early research that focused specifically on the individual’s personality, without exploring other factors that may influence a person to behave in a deviant or antisocial manner. The next section explores not only personality factors, but also other influences that may affect whether a person will become a delinquent and commit crimes, such as family circumstances and living conditions.

2.1 Personality/family factors

Hans Eysenck was a psychologist who was interested in studying what made people different from one another, such as personality.

Activity 3

What is personality? Think of five words that describe you (not your appearance). For example, are you talkative, shy, and so on? Do you think you could have used those words to describe yourself ten years ago, or in ten years’ time?

Now think of a family member or close friend and think of five words that describe them. Do you have any characteristics in common or are they all different?

Discussion

Personality has been described as a set of fairly stable characteristics that makes a person unique, but also allows for comparison with other individuals. Social scientists have been interested in the study of personality for many years, and numerous personality theories have been developed to try and explain why people behave in a certain way.

Many people frequently make judgements about other people’s personalities, for example when telling a story, a person may be described as ‘outgoing’, ‘reserved’ or ‘argumentative’. Sometimes a person’s personality and how they react to a situation can be the driving force of an interesting tale. Therefore, maybe it is not unreasonable to suggest that some people’s personality may make them more likely to behave in a deviant way, or commit crimes, as compared to other people.

Eysenck was one of the first researchers to develop a theory linking personality to deviant or criminal behaviour. In Eysenck’s (1947) theory, he suggested that personality could be reduced to two dimensions, sometimes simply referred to as ‘E’ and ‘N’:

- extraversion (E)

- neuroticism (N).

These factors could be measured using a self-report questionnaire that required people to simply answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a series of questions contained in the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) (Eysenck and Eysenck, 1968). People who scored high on the E scale were classed as extravert and were lively, sociable, thrill seeking and impulsive. Those who scored low on the E scale were classified as introvert, and were quiet, retiring and may like books more than people. On the N scale, those who score more highly may be anxious, depressed and preoccupied that things may go wrong. Those who had low scores on the N scale were relaxed, recovered quickly after an emotional upset and were generally unworried.

2.1.1 The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire

In a later version of his theory, Eysenck added another component, psychoticism, also referred to as ‘P’. People who scored highly on the P scale were aggressive, lacking in feeling and antisocial, while those with a low P score were warm, caring and non-aggressive. Eysenck updated the personality scale to include the P dimension in the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ) (Eysenck and Eysenck, 1975).

This figure depicts the different dimensions of Eysenck’s theory of personality.

The first row shows the dimension for ‘Extraversion’ or ‘E’ with a double-headed arrow. ‘Low’ extraversion is on the right and underneath is ‘unsociable, cautious’. ‘High’ extraversion is on the left, with ‘sociable’ and ‘sensation seeking’ below.

The second dimension is ‘Neuroticism’ or ‘N’ with a double-headed arrow below. On the right is ‘low’ neuroticism with ‘calm, relaxed’ underneath. On the left is ‘high’ neuroticism with ‘tense, anxious, irrational’ underneath.

The third dimension shows ‘Psychoticism’ or ‘P’ with a double-headed arrow below. On the right is ‘low’ psychoticism, with ‘non-aggressive, warm, aware of others’. On the left is ‘high’ psychoticism, with ‘aggressiveness, selfish, lacking in feeling’.

Eysenck thought that most people would score in the middle of the E and N scales, but at the lower end of the P scale. However, criminals would score at the higher end of each of the scales. Eysenck believed that there was a biological basis for personality and that extraversion and neuroticism related to arousal from the nervous system (biological approach). People who scored highly on the E scale (extraverts) had low arousal levels, therefore they would seek arousal from their environment, such as socialising and thrill-seeking activities. Whereas those who had low scores on the E scale (introverts) already had an over-aroused nervous system and therefore would seek out situations that minimised or reduced their arousal, such as reading a book. People who scored highly on the N scale had a nervous system that was more easily aroused or reacted more strongly to stressful situations (Eysenck, 1964).

Eysenck suggested that the link between personality and antisocial or criminal behaviour was due to differences in learning during childhood. According to the theory, as children grow up they learn right and wrong behaviours by developing a conscience. A conscience develops through conditioning, where unapproved or wrong behaviours receive punishment or disapproval. Therefore, children learn to avoid behaviours that will lead to punishment or disapproval and control their impulses. Children who were higher on the E and N scales would find it more difficult to learn during childhood, as they were harder to condition. As a result, those with higher E and N scores may not develop a conscience, or correctly learn right from wrong, and may have problems with controlling their impulsive behaviour. Then in later life, those who had not developed a conscience, and had a tendency towards impulsive behaviour, may be more likely to act in antisocial ways and commit crime. Eysenck suggested that according to his theory, offenders would score more highly on each of the three scales of the EPQ, as compared to non-offenders.

Activity 4

Questionnaires are a good research method to use when you want to collect data from a large number of people. Many questionnaires can be given out for people to complete and return, or respondents can be emailed a link to an online survey.

- Can you think of any problems in using a questionnaire to research an issue?

- What if you didn’t want someone to know how you really felt about an issue, or behaved in a particular situation, because you were embarrassed or ashamed?

- Do you think you would answer all the questions truthfully?

Discussion

One of the problems with using a questionnaire to collect data is that people may not tell the truth, as they want to be seen in a good light and favourably by others. This is the social desirability effect, whereby good behaviour is over-reported and bad behaviour is under-reported. This can really influence the findings from research, as it may not reflect the true frequency of behaviour.

To try and determine whether respondents were telling the truth when completing the EPQ, Eysenck included a Lie (L) scale. In the L scale, there are items that try to determine whether the respondent is giving the socially desired response or telling the truth. For example, a question on the L scale could be something like ‘I always try not to be rude to people’. A high score on the L scale is thought to indicate that the respondent is giving the socially desired response; a low score may indicate indifference to social expectations, as the respondent is not thinking about responses that are socially desirable. Therefore, those who have a propensity towards antisocial and criminal behaviour may have low scores on the L scale, as they do not think about what is socially desirable behaviour (Eysenck and Gudjonsson, 1989).

2.2 Evidence for Eysenck’s theory

Over the years, Eysenck’s theory of personality has received support from some psychologists, but has also received criticisms from others. Eysenck’s theory has been praised for combining the biological (arousal from the nervous system) and social (learning throughout childhood) elements to try and understand why people’s personalities differ, and why some people may commit criminal acts. However, it has also been criticised that there is little evidence that extraverts are more difficult to condition than introverts (Gross, 1996). This is an important aspect of the theory as it points to the biological basis for personality; however, if there is no research evidence to support it, then it weakens the theory that extraverts do not learn to develop a conscience through conditioning.

A number of studies have used Eysenck’s personality questionnaires to determine whether there really is a difference between those who act in antisocial or deviant ways, compared to those who do not. Center and Kemp (2002) compared the results of 60 studies with children and adolescents who were grouped as exhibiting ‘antisocial behaviour’ or ‘normal behaviour’, and were asked to complete an EPQ. When all the results were compared, they found that those who were labelled as exhibiting antisocial behaviour were more likely to score highly on the P scale compared to those who were labelled as normal. Those who were labelled as exhibiting antisocial behaviour were also more likely to have a low L score, giving further support to the theory that those who exhibit antisocial behaviour do not think about whether their actions are perceived as socially desirable. However, there were few differences between groups on the E and N scales, which do not support Eysenck’s theory.

There are several studies that have used adult participants to determine whether offenders in prisons differ in their personality according to Eysenck’s dimensions, as compared to non-offenders. Bourke et al. (2013) surveyed prisoners and found that those who were re-offenders (who have offended more than once) scored more highly on the P scale and were lower on the E and N scale compared to those who were first-time offenders. Boduszek et al. (2013) found that violent offenders scored more highly on the P scale. These studies seem to suggest there is some evidence that offenders can score differently to non-offenders on Eysenck’s personality questionnaire; however, offenders are more likely to score highly on the P scale and either no differently or even lower than ‘normal’ participants on the E or N scales.

Activity 5

- Now you have read about Eysenck’s theory of personality, do you agree with his dimensions of personality, or do you think that there are characteristics not covered in his theory?

- Do you think there could be other factors apart from a person’s personality that might influence them to behave in a deviant or antisocial manner and maybe even commit crime?

Discussion

The next section goes further than Eysenck’s theory, and although it does accept that personality may be a factor that affects how people behave in certain situations, it also suggests that there are additional factors that may influence a person’s behaviour and their propensity to commit crime.

2.3 The Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development

One method that social scientists use to investigate the causes of antisocial and criminal behaviour is to study a large group of children over a long period of time, and see if any of them commit crimes. Differences between the group can then be explored, for example personality, home life, economic circumstances and so on, to try and determine why some go on to commit crime, as compared to others who do not. This type of research is called a ‘longitudinal study’, as it follows people over a long period to see if their behaviour changes or develops over time.

The Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development was a longitudinal study that began in the 1960s by the criminologist Donald West, although David Farrington, a forensic psychologist, took over the long-term running of the project. The study followed a group of 411 males from the age of 8 years (in 1961), up to the age of 48 years. All the boys were from working-class backgrounds and living in a deprived area of south London. The aim was to investigate the development of delinquent and criminal behaviour in inner-city males, and whether it was persistent over time. The study was not designed to test any one theory of delinquency, but to try and investigate:

- why delinquency began

- whether it could be predicted in advance

- if it continued into adult life.

The boys who took part in the study were interviewed and tested nine times throughout the study. The tests measured individual characteristics, such as personality and intelligence. The interviews investigated issues such as living circumstances, employment, relationships, leisure activities and offending behaviour. When the boys were at school, their teachers also filled out questionnaires about their behaviour and school attainment; and their peers were asked about issues such as popularity, risk-taking behaviour and honesty.

When the males reached 32 years of age, criminal record checks were conducted to determine how many had commited criminal offences and what type of offences they were. The study found a number of predictors at 8–10 years of age, which were thought to be related to later delinquency and offending. These fell into six categories (Farrington, 1995; Farrington et al., 2006):

- Antisocial behaviour, including being troublesome in school, dishonesty and aggressiveness.

- Hyperactivity, attention deficit disorder, daring, risk-taking and poor concentration.

- Low intelligence and poor school attainment.

- Family criminality, convicted parents, older siblings and siblings with behavioural problems.

- Family poverty, large family size and poor housing.

- Poor parental child-rearing behaviour, including harsh and inconsistent discipline, poor supervision, neglect and parental conflict.

The study also found that when the men were aged 32, just over a third (37 per cent) had been convicted of a criminal offence. This rose to only 41 per cent when the men were surveyed at 48 years. The most frequent number of offences were committed when the men were aged 17−20 years of age, suggesting that if males were at risk of becoming criminals, then this was the age at which they were most likely to offend. Farrington et al. (1986) found that the men in the study were more likely to commit offences while they were unemployed, as compared to being employed. When the types of offences were examined, it was found that the increase in offences when unemployed centred on offences that involved material gain, such as theft, robbery and fraud, and not offences that involved violence. This suggests that a shortage of money during unemployment may have been an increasing risk factor that led to crime.

The findings from the Cambridge study show that personality is an important factor in whether someone commits crime, for example those who are impulsive and like to take risks are more likely to commit crime. However, the findings from the study also showed that there were other factors in addition to personality that may influence young people to act in antisocial ways or commit criminal acts. The additional risk factors thought to be associated with future criminal behaviour included a family history of offending, child-rearing practices and family poverty. However, which risk factors were considered to be the most important or how they interacted with each other were not discussed in the findings from this study.

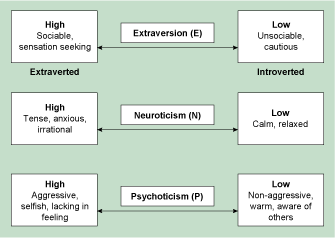

2.4 Integrated Cognitive Antisocial Potential theory

Using the findings from the Cambridge study, Farrington alone (1995; 2003; 2005) and in collaboration with colleagues (2006) was able to develop a theoretical model looking at the risk factors for crime called the Integrated Cognitive Antisocial Potential (ICAP) theory. The ICAP theory was designed to try and explain the offending behaviour of males from working-class families. The main concept is a person’s antisocial potential (AP), which is their potential to commit antisocial acts and their decisions to turn that potential into the reality of committing crime. Whether the AP is turned into antisocial behaviour depends on the person’s cognitive processes that consider opportunities and victims.

According to the ICAP theory, individuals can be placed on a continuum, from ‘low’ to ‘high’ AP, and although few people have a high AP, those who do are more likely to commit crimes. The primary factors that influence high AP are:

- desires for material gain

- status among peers

- excitement and sexual satisfaction.

However, whether these issues influence behaviour will depend on whether the individual can use legitimate means to satisfy them. For example, people from low incomes, the unemployed and those who are not successful at school may be more likely to engage in antisocial behaviour. This theory therefore suggests that males from low-income families with low school attainment and who are unemployed are more likely to commit crimes to achieve material gain (for example, the latest mobile phone), as compared to others from different backgrounds.

This figure depicts the factors that can influence a person’s potential to commit crime. There are a number of factors with arrows pointing towards the factors they may influence. The first factor is desires and material gain, the second is low family income’, the third is low school achievement and the fourth is sensation seeking. All of these factors point to ‘long-term antisocial potential (AP)’.

An arrow points from long-term antisocial potential (AP) to short-term antisocial potential (AP). Two further boxes on either side are joined by arrows, showing the influences on short-term antisocial potential. One is drugs and alcohol and the other is boredom and frustration. A further arrow points down from short-term antisocial potential (AP) to cognitive processes. Another arrow points from cognitive processes to delinquent behaviours and crime. The final arrow points to reinforcement, for example punishment and reward.

The ICAP theory also suggests that there are long-term and short-term factors for AP. Individuals with long-term AP tend to come from poorer families, be poorly socialised, impulsive, sensation seeking and have a lower IQ. For example, children who are neglected or receive little warmth from their parents may care less about parental punishment and therefore do not learn to avoid behaving in antisocial ways. Individuals with short-term AP may not necessarily have been affected by these issues, but may temporarily increase their AP by situational factors, such as frustration, anger, boredom or alcohol. These situational factors may influence a person to make decisions about their behaviour that they may not make in other situations. Furthermore, short-term AP can develop into long-term AP depending on the consequences of antisocial behaviour or offending. If the consequence for offending is material gain, status and approval from peers, it is likely to be repeated. However, it may be a different matter if the behaviour leads to disapproval or imprisonment.

The ICAP theory also looks at factors that might prevent an individual from offending, and these can be social and individual reasons. For example, as a person gets older they tend to become less frustrated and impulsive. There may be important life events that reduce AP, such as marriage, steady employment or moving to a new area, which can shift interaction with peers to girlfriends, wives and children. Farrington (2003) suggests that these life events can have a number of influences to reduce AP. They can:

- decrease offending opportunities, by shifting routine activities such as drinking with male peers

- increase informal controls of family and work responsibilities – spending time with family or working may become more important than socialising with peers

- change decision making by reducing the subjective rewards of offending because the risks of being caught are higher than they previously were, for example disapproval from partner, threat of incarceration and leaving the family.

Farrington (2003) believed that as this theory established a number of risk factors for offending, it would be possible to develop some interventions to prevent those identified as most at risk from offending. For example, cognitive–behavioural skill training to help reduce impulsive behaviour, and parental education to help promote good child-rearing practices and improve parental supervision.

2.4.1 Strengths and weaknesses of the ICAP theory

One of the strengths of this theory is that it identifies different factors that may influence future criminal and antisocial behaviour, and how criminal behaviour may have short-term or long-term risk factors. As a result of their focus on risk factors associated with offending, the ICAP theory, along with findings from the Cambridge study, have been very influential in the development of programmes to try and reduce offending.

The ICAP theory focuses on risk factors of those who go on to commit crimes; however, there is research that has shown that many people can have these risk factors, but do not later go on to be offenders (Webster et al., 2006). The ICAP theory has also been criticised for only focusing on risk factors related to family, parenting and peer groups, while neglecting wider issues, such as the role of the neighbourhood (Webster et al., 2006).

- Now that you have read about the Cambridge study and the ICAP theory, do you think that they adequately explain why some people may be more likely to commit deviant acts, or crime, as compared to other people who do not?

- Most of Farrington’s research and his theory focuses on males from working-class backgrounds – can you see any problems with focusing on this specific group?

- Do you think that this research and the ICAP theory could be used to explain why other groups in society such as females and those from middle or upper classes, or even rural areas, may commit deviant acts and go on to become offenders?

2.5 Activity: Exploring delinquent behaviour

You will now listen to an interview with Professor John Muncie, a criminologist at The Open University, in which he discusses the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development and its attempts to predict which individuals may become offenders later on in life.

Activity 6

Click on the audio player beneath each question to hear Professor John Muncie’s response to that question and note his answer in the box provided. To do this, you don’t necessarily have to write in full sentences: bullet points, lists or brief notes are all acceptable as long as they work for you.

1. In your own words, jot down what John Muncie says about the features and aims of the study.

Transcript: Delinquent development 1

Discussion

- This was a longitudinal study which means it was carried out over a long period of time during which the young people being studied were contacted nine times from their childhood into adulthood.

- The sample, although consisting of 411 children, was mainly male, white and working class.

- The study aimed to discover the factors to explain why some children became delinquents.

2. Summarise, in your own words, the findings of the study.

Transcript: Delinquent development 2

Discussion

The main findings were:

- A fifth of the sample had been convicted of criminal offences as juveniles.

- A third had been convicted by the time they were thirty-two.

- Six per cent of the sample was labelled chronic offenders who shared some common childhood characteristics.

3. Jot down, in your own words, the individual, family and environmental risk factors the study identifies.

Transcript: Delinquent development 3

Discussion

- Individual risk factors were low intelligence, personality and impulsiveness.

- Family factors were criminal and anti-social parents, poor parenting and a disruptive family life.

- Environmental factors were associating with similar friends, living in poor areas and attending schools with high delinquency rates.

4. What weaknesses does Professor Muncie highlight with using these risk factors to identify potential young offenders?

Transcript: Delinquent development 4

Discussion

- Professor Muncie argues that out of this list of risk factors it is impossible to know which are the most important and we don’t know how these factors influence each other.

- Most significantly, although this research shows links between certain risk factors and juvenile delinquency, it doesn’t explain what causes juvenile delinquency.

5. What weaknesses of the Cambridge Study have been identified by further research?

Transcript: Delinquent development 5

Discussion

- A study in the north-east of England based on interviews showed that risk factors couldn’t explain why some children, who had many of these risk factors, did not offend.

- Another study in Pittsburgh highlighted the economic status of neighbourhoods as a more important risk factor than individual personality or family background.

2.6 Summary

The previous sections explored the micro theories of criminal behaviour that focus on individuals, and why some people commit crimes and others do not.

- Psychological theories look at the risk factors for individuals to commit crime, not society more widely or why certain groups of people may commit crime.

- Eysenck’s theory looked at the link between biology, personality and crime, and suggested that people who commit crimes score more highly on the three scales of extraversion (E), neuroticism (N) and psychoticism (P).

- Eysenck’s theory has been praised for combining the biological and social processes to try and understand why some people commit crimes and others do not. Yet, research using Eysenck’s personality measures, the EPI and the EPQ, has failed to find support for Eysenck’s claim that offenders score more highly on the three scales, as compared to non-offenders.

- Farrington’s ICAP theory and the Cambridge study looked at risk factors that could potentially lead a person to commit crime. Personality is one risk factor for crime; other factors include size of family, poverty, child-rearing practices, school attainment and employment.

- The ICAP theory also examines situational factors that may influence a person to behave in a deviant way, for example alcohol, drugs, and feelings of boredom and frustration.

- The ICAP theory has been praised for its emphasis on short-term and long-term risk factors that may lead to crime, and has been influential in implementing programmes to try to reduce offending. However, the ICAP theory has been criticised for not taking into account the influence of the neighbourhood on offending.

3 Studying the control of disorder

You are now going to look at sociological approaches to disorderly behaviour. In contrast to the psychological approaches that you have just examined, which study juvenile delinquency to find out why some individuals commit crimes while others do not, sociologists start with an entirely different question: not, why did this person commit this crime, but why is this behaviour and this person viewed as disorderly?

3.1 Howard Becker and the turn to control

In 1963, the American sociologist Howard Becker published Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance, which laid the foundations for a very different approach to studying deviant, criminal and delinquent behaviour. Becker’s work started from a rather mundane observation: not everyone who breaks the law is caught and prosecuted. This fact falls into the ‘everybody knows’ category of knowledge, but Becker turned it from a rather dull observation into a different way of thinking about deviant behaviour. He drew four related arguments from it:

- Most studies of delinquents/criminals that seek to explain the causes of crime are methodologically flawed. They tend to assume a reliable distinction between a normal group and a deviant group, and search for the factor(s) that make the difference between the two. Do deviants have the wrong chromosomes, the wrong parenting, the wrong friends, the wrong environment, and so on? But, for Becker, the only reliable difference between the two groups was that one group had been identified – labelled – as deviant/criminal. The others – the normals – might have done exactly the same things, but had not been detected, processed and labelled as deviant (see Table 1). It might also be the case that among the ‘deviants’ were people who had been falsely accused and labelled – people who had not committed the criminal or deviant act. So the search for the X factor (that made the difference) was fundamentally flawed.

| Detected and labelled | Not detected or labelled | |

|---|---|---|

| Committed the act | Positive (Deviant) | False negative |

| Did not commit the act | False positive | Negative (Normal) |

- Becker argued that social scientists should therefore pay much more attention to the processes involved in identifying some acts – and some people – as criminal or deviant. Why are some behaviours and some types of people the focus of attention? What processes of selection are involved in these processes of social control? Are they merely random (some people are just unlucky to be caught and prosecuted) or do they have social biases or logic? Becker asserted that this meant breaking the fundamental assumption that treats deviance as the:

... infraction of some agreed-upon rule: such an assumption seems to me to ignore the central fact about deviance: it is created by society. I do not mean this in the way that it is ordinarily understood, in which the causes of deviance are located in the social situation of the deviant or in ‘social factors’ which prompt his [sic] action. I mean, rather, that social groups create deviance by making the rules whose infraction constitutes deviance, and by applying those rules to particular people and labelling them as outsiders. From this point of view deviance is not a quality of the act the person commits, but rather a consequence of the application by others of rules and sanctions to an ‘offender’. The deviant is one to whom that label has been successfully applied; deviant behaviour is behaviour that people so label.

- It is important to note that Becker makes a distinction between the behaviour and the person. Societies decide which behaviours are ‘deviant’ (and they make some of them illegal – crimes). Societies do not necessarily share the same judgements about what should be judged as deviant or criminal. For example, not all societies judge ‘hate crimes’ (attacks motivated by hatred of a person’s ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion) as crimes or even deviant , although the UK now recognises such actions as criminal. Killing people is usually thought to be both deviant and criminal, but societies vary in the exemptions they permit (it may depend on who commits the act: agents of the government often have some immunity – think about soldiers in wartime or deaths in police custody; deaths that result from corporate action rarely result in murder charges). Indeed specific societies may change their judgements over time (for over a century, the UK treated homosexual acts between consenting male adults as crimes, but ‘de-criminalised’ them in 1967). Second, though, some people performing those behaviours are identified and labelled as deviant (or criminal), but perhaps not everyone who acts in these ways is identified and labelled.

- Becker also argued that labels could have powerful consequences. Drawing on the social interactionist approach in social psychology (from the work of George Herbert Mead, 1863–1931), Becker suggested that how others define us may well shape how we act: if we are labelled as ‘bad’ or ‘criminal’, we might start to live up to the label. Equally, the label may shape how others treat us – once labelled, people identified as criminals or deviants may face extra scrutiny, suspicion or even discrimination. A powerful label changes the situation – for the person so labelled and for others. For Becker, the arrival of a label created the conditions of people moving into a ‘deviant career’: the label shapes the possible future directions of both identity and action.

3.2 Labelling and deviance

Activity 7

Can you think of any other examples of labels that might re-shape the conditions of a person’s future possibilities?

Discussion

What about medical or psychiatric diagnoses; being identified as a ‘citizen’ or an ‘alien’; being described as a ‘scrounger’; being called a ‘job seeker’ rather than an ‘unemployed person’; becoming homeless; becoming a mother?

Becker’s work has been influential in sociological approaches to the study of delinquency, deviance and social control. In fact, he put the processes of social control into a more dramatically visible position, exposing their role in ‘defining the situation’. We will now trace some of the issues that emerged from Becker’s focus on ‘labelling’.

One issue that emerges is the selection of what sorts of behaviour are to be defined as criminal or deviant. Remember that criminal behaviour is defined as that which breaks the criminal law; while deviant behaviour is that which breaks established social rules or norms of conduct. But this very general definition conceals a more important question for social scientists about how both the criminal law (in a particular society) and social norms change over time. If we take the criminal law in England and Wales (Scotland and Northern Ireland have different legal systems, even if many of the offences overlap), then it has changed in important ways. New offences are sometimes added: over 3500 during the Labour governments between 1997 and 2010 (see, for example, Slack (2010) or Morris (2008)). Sometimes, established offences are deleted or downgraded: it is no longer possible to be executed, imprisoned or transported for stealing timber, turf or peat from the King’s Forests (see E.P. Thompson’s study (1977) of the Black Act of 1723, which created 50 new criminal offences). Similarly, the content of social norms changes – reflecting shifting views of what is normal, right, proper or reasonable.

It is important to remember that neither the law nor social codes are permanent and unchanging. They change over time and are different from country to country (or from one legal jurisdiction to another).

3.3 Agencies of control: being selective

It is equally important to remember that rules may be applied selectively. In democratic societies subject to the Rule of Law, the principle of ‘equality before the law’ is an important political value. However, investigations of how the criminal law is applied suggest that forms of social difference and inequality may have a significant impact on who gets ‘labelled’. There are numerous examples of distinctions being made between similar behaviour that is judged differently depending on the social identities of the actors. For instance, rowdy, noisy behaviour involving forms of criminal damage to property may be viewed as criminal or delinquent behaviour if done by young working-class men, but treated as ‘high jinks’ or ‘youthful high spirits’ if perpetrated by middle- or upper-class young men.

Activity 8

Read the following extract about the ideas of criminal damage in the aftermath of the English riots of 2011 and reflect on whether the comparison at stake is between types of behaviour or types of people.

‘An excessive sense of entitlement’ was what the mayor of London ascribed to those looting their way across our sceptred isle – but he could have been referring to himself. In the mid-to-late 80s, Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson – not to mention David Cameron and his now chancellor George Osborne – were members of the notorious Bullingdon Club, the Oxford University ‘dining’ clique that smashed their way through restaurant crockery, car windscreens and antique violins all over the city of knowledge.

Not unlike a certain section of today’s youth, the ‘Bullers’ have little regard for property. Prospective members often have their rooms trashed by their new-found friends, while the club has a reputation for ritualistic plate smashing at unsuspecting country pubs. It has been banned from several establishments, while contemporary Bullers are said to chant, at all hours: ‘Buller, Buller, Buller! Buller, Buller, Buller! We are the famous Bullingdon Club, and we don’t give a f***!’

We can see some of these differentiating social dynamics at work in the definition and control of juvenile delinquency. It is understood as a male problem: most concern about delinquency – and most arrests and prosecutions of young people – concentrate on young men. Young women have historically been the focus of rather different anxieties – fears about moral or sexual delinquency have dominated. More recently, however, are worries that young women are behaving like young men – sometimes calling them ‘ladettes’ or ‘yobettes’, as in the Daily Mail headline ‘Yobette generation is plaguing our streets’ (Wharton, 2007). John Muncie, writing about the difference between male and female juvenile offending, noted that:

Fuelled by media-driven panics about a ‘new breed’ of girl gangs, the numbers of girls convicted of indictable offences rose, the use of diversionary measures (cautions, reprimands and warnings) decreased and the number sentenced to immediate custody increased dramatically (by 365 percent between 1993 and 2002) (Gelsthorpe and Sharpe, 2006).

3.3.1 Official statistics and self-report studies

We will return to Muncie’s observation about ‘media-driven panics’ in the following section, but here we want to consider other patterns of social difference in relation to the control of juvenile delinquency. Using two different types of evidence, sociologists have pointed to a systematic difference between who breaks the law and who is officially labelled as law-breaking. On the one hand, official statistics about crime – data collected by the criminal justice system that records arrests, prosecutions, sentences, and so on – identifies delinquency and criminality as a behaviour associated with young working-class men. On the other hand, self-report studies – in which people report their own law-breaking activities anonymously – tend to contradict this apparent distribution. Muncie summarises the situation as follows:

… the major contribution of self-report studies has been to seriously question widely held beliefs about the correlations of class position, ‘race’ and gender to criminality. Both Anderson et al. (1994) and Graham and Bowling (1995) found that middle-class children were just as likely to be involved in crime as working-class children. Indeed a survey by the British Household Panel in 2001 based on interviews with 1,000 13−15 year olds found that those from higher income families were more likely to commit vandalism, play truant and take illegal drugs (Guardian, 25 February, 2001) … This suggests strongly that official statistics reflect not patterns of offending but patterns of policing. As a result, the relative criminality of certain groups of young people has been exaggerated. For example, inner-city working-class youths face a greater risk of arrest than middle-class youths engaged in similar activities but in areas where the police presence is lower. Ethnic minority youths are statistically more likely to be stopped and searched by the police (Burke, 1996), but self-report studies show that those of Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin have significantly lower rates of offending and that for African-Caribbeans the rate is no higher than for whites.

There are two important points to draw out of this discussion. The first concerns the problem of evidence in relation to delinquency and criminality. Two types of data – official statistics and self-report studies – produce very different pictures of the social distribution of law-breaking behaviour. Each of them has problems. As Muncie suggests, official statistics tend to report police activity rather than law-breaking. Self-report studies also have potential flaws, as people may be selective about what they admit to; or may even over-dramatise their law breaking when hidden behind anonymity. Such studies tend to be conducted through questionnaires with relatively low response rates; and tend to focus on a limited set of crime behaviours (leaving out a range of possible crimes – from large-scale financial fraud to child abuse). Evidence in the social sciences is rarely perfect, but here it is the comparison between the two sorts of data that is the point of interest.

The second important point concerns the shift of attention to the processes of social control, and their critical role in defining and acting on what – and who – counts as deviant. This concern with ‘defining the situation’ inspired a wide range of investigations into crime, deviance and social problems more generally. For example, Bacchi’s work (1999) builds this starting point into an analysis of social policies and their relationship to gender divisions, arguing that the power or capacity to define ‘what the problem is’ is central to the policy-making process. This issue is also central to other work on youthful disorder.

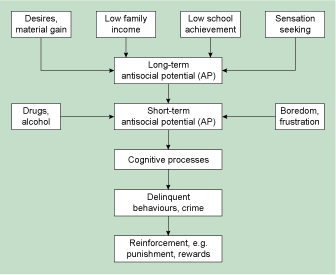

3.4 Media and moral panics

The sociologist Stan Cohen published a widely used study (1972) of the social reaction to fights between Mods and Rockers (two rival youth subcultures) at English seaside towns during the 1960s. Cohen analysed the media’s reporting of these events and found them to be highly dramatised, turning rather banal events into sensational – and sensationalised – news. He pointed to the ways in which these groups of young people were demonised, and viewed as posing a major threat to the stability of social order in the UK. He called this process of demonisation the creation of ‘folk devils’ – invented figures onto whom a whole variety of problems, dangers and anxieties could be projected.

At the heart of this process was a relationship between the mass media and figures of authority (judges and magistrates, senior police officers, politicians and others whom Cohen described as ‘moral entrepreneurs’ who saw an opportunity to speak out about the ‘state of the nation’ and the dangers posed by such young people). The mass media – print journalism, radio and television – provided the forum in which figures of authority could pass judgement, issue dire warnings and demand strong action. Cohen described this process as the creation of a moral panic, which he described as taking place when a ‘condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests’ (1972, p. 9). The important point here is the idea of ‘become defined as’. Cohen’s study suggests that the fights between Mods and Rockers were treated disproportionately by the media and those in authority. In the process, they had other concerns and social anxieties projected onto them. The ‘definition of the situation’ turned the Mods and Rockers into a major threat to the future of the social order – and they were treated according to that definition (a combination of public condemnation, heavy policing and tough sentencing). Finally, Cohen suggests that the creation of folk devils and the development of moral panics – although certainly irrational and disproportionate – served some social interests. The Mods and Rockers gave a platform for ‘moral entrepreneurs’ to tell stories about the state of the nation and its young people; for judges and magistrates to ‘defend the public’ through tough sentencing; and for senior police officers to demand more resources in order to respond to this new threat to society. And, just as Becker suggested, the process of labelling had effects on those being labelled – such that Mods and Rockers tried to live up to their new public reputations: learning to perform their roles in the drama.

Cohen used the idea of a ‘deviancy amplification spiral’ in which the media’s dramatisation of particular events increased their visibility and the anxieties about them, such that campaigns by police, politicians, the judiciary and representatives of ‘concerned citizens’ increased the public focus on these actions and the ‘folk devils’ held responsible for them.

This figure depicts a circular figure with paragraphs of text connected in a circle by arrows. The top centre text says ‘public definition of crime’ as the title. The text underneath says ‘consequences of selective knowledge about crime: fear, less tolerance, calls for crackdowns, etc. …’ This text is joined by an arrow to the right that says ‘crime’ as the title. Then the text underneath says ‘as defined by crime control agencies’. There is another arrow coming down from the top right from this text, which says ‘deviant act’. From ‘crime’, another arrow goes down into the title ‘operation of news values’. The text underneath says ‘selective practices of news making’. This text is then joined by an arrow now going to the left to the following text, ‘crime as news’ with ‘selective portrayal of crime in the media’ below. This text has an arrow now going up to the left towards the title of ‘deviancy amplification’. The text underneath this says ‘targeting of news, public concern and crime control agencies on particular aspects of deviance. Perceived and real increases in deviance’. From this text is another arrow pointed upward and left to ‘moral panic’ with ‘law and order campaign’ below it. The final arrow closes the circle back to ‘public definition of crime’.

In the conclusion to the book, Cohen argued that this distinctive set of dynamics – identifying folk devils, dramatising them as other and dangerous, creating a moral panic about the threat that they pose to the social order, and amplifying the reaction to them (tougher policing, tougher sentences, and so on) – would recur:

More moral panics will be generated and other, as yet nameless, folk devils will be created … our society as presently structured will continue to generate problems for some of its members … and then condemn whatever solution these groups find.

3.4.1 The ‘yob culture’

Many studies have borrowed the ideas of folk devils and moral panics from Cohen, exploring the tendency of societies to enter into this cycle of discovering dangers, projecting fears and anxieties onto them, and demanding harsh responses to ‘protect society’ (see the discussions by Critcher, 2003 and 2008; Garland, 2001; Jewkes, 2004). Young people seem to be particularly vulnerable to being portrayed as ‘folk devils’ in this way. For example, Coward (1994) has reflected on the way in which ‘yobs’ and ‘yob culture’ came to be powerful images of social crisis and disorder during the 1990s:

‘YOB’, once a slang insult, is now a descriptive category used by tabloid and quality newspapers alike. Incorporating other breeds, like the lager louts, football hooligans and joyriders, yob is a species of young, white, working-class male which, if the British media is to be believed, is more common than ever before. The yob is foul-mouthed, irresponsible, probably unemployed and violent. The yob hangs around council estates where he terrorises the local inhabitants, possibly in the company of his pit-bull terrier. He fathers children rather than cares for them. He is often drunk, probably uses drugs and is likely to be involved in crime, including domestic violence. He is the ultimate expression of macho values: mad, bad, and dangerous to know.

The yob is the bogey of the Nineties, hated and feared with a startling intensity by the British middle class … Individual men disappear in this language into a faceless mob, or appear only as thuggish stereotypes.

Can you identify any current ‘folk devils’?

3.5 ‘Society must be protected’: crises and control

One important study that drew on and extended Cohen’s work was by Stuart Hall and his colleagues (1978), which examined the construction of a moral panic about ‘mugging’ (street robbery) in Britain during the early 1970s. A term that had not been used since the nineteenth century was suddenly discussed in the mass media as a ‘frightening new strain of crime’, possibly arriving from what the British perceived as the violent, dangerous and racially divided USA. ‘Muggers’ became a new type of folk devil, identified as a threat to stability and social order, and requiring tough measures to protect society. Hall et al. argued that this invention of ‘mugging’ needed to be understood as part of wider social and political dynamics.

They explored the different sorts of disorder that shaped British society at the beginning of the 1970s: a deepening economic crisis and a stagnant economy; growing political conflict; a variety of social divisions that were becoming more severe; and a loss of public confidence in the nation’s political leaders. Describing a time in which a relatively consensual society in the 20-year period following the Second World War was becoming increasingly characterised by economic, social and political conflicts, they claimed that the figure of the ‘mugger’ was placed in the middle of this crisis. He (muggers were usually imagined as men – young, black men to be more precise) became the focus of social and political anxiety – the ‘mugger’ was seen to represent the breakdown of law and order. As a result, the mass media were full of denunciations, dire warnings and demands for tough action to be taken to save the country from this appalling threat.

3.5.1 Police powers

For Hall et al., this invention was a way of displacing genuine social and political tensions onto a folk devil. Attention could be deflected from the deepening crises. Society would be protected – not by overcoming divisions – but by ‘cracking down’ on young black men on the nation’s streets. Getting tough on mugging created new police powers, brought about ‘exemplary’ sentences for those found guilty of robbery (mugging was never a crime in a legal definition), and exposed young black men to a programme of systematic harassment by police officers (under what became known as the ‘sus’ law: the right of police officers to stop anyone that they suspected might have committed a crime or be intending to commit a crime). The ‘suspicious person’ powers derived from Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act 1824 and became a major point of conflict between the police and the black community in Britain (especially in London: see Whitfield, 2004). It was eventually abolished in the early 1980s (following the Scarman Report’s recommendation of the need for more integrative ‘community policing’) but re-emerged in a new guise as the power to ‘stop and search’. The new power continued to be deployed in an ethnically discriminatory way (what in the USA is known – and condemned – as ‘racial profiling’). Whitfield indicates that:

Ministry of Justice figures published in October 2007 reveal that black and Asian people are more likely to be stopped and searched than their white counterparts. This is especially the case in London where, in 2005/06, black people were more than seven times more likely to be searched than whites. Outside London, they are 4.8 per cent more likely to be searched.

For Hall et al., ‘mugging’ helped the politically dominant groups in Britain to move attention from social divisions and political conflict onto a group of folk devils, and to argue that society needed to be protected through tougher policing and a generally stronger state. In ‘cracking down’ on crime and violence, particularly among young black men, the state (seen by Hall et al. to be representing the most powerful groups and interests in society) became a ‘primary definer’ of disorder. The media then took their cue from government, police and judges – for instance, in the use of the term ‘mugging’ – and extended the primary definitions further, giving them a popular ring. In this view, the deep-seated causes of social conflict, chiefly inequality, were obscured and the issue was turned into a legal and moral struggle against what was defined as ‘mindless violence’. Hall and his colleagues described this as the creation of a ‘law and order society’ in which those defined as the enemies of the nation would be rooted out and subjected to increasingly harsh treatment. The analysis they presented has proved to be both very powerful (the book was reissued on its thirty-fifth anniversary in 2013) and very controversial. Debates about it continue that address its account of the British political situation, the relationship between institutions of social control and the mass media, and its view of the situation of young black men in Britain (see, for example, Jewkes (2004) and the special issue of the journal Crime, Media, Culture published in April 2008 (Clarke, 2008)).

Perhaps the most interesting question that emerges from the Hall et al. study is whether we are still ‘policing the crisis’: deflecting attention away from economic crises, social divisions and political conflict by focusing too much on the deviant behaviour of young people and the need to impose a ‘law and order society’ (Clarke, 2008). Following the English riots of August 2011, it was possible to trace very different views: between those who denounced the ‘pure criminality’ of the rioters; those who sought to explain rioting in terms of the social and economic conditions facing young people (young men, in particular); and those who suggested that the reaction to the riots was also a displacement of larger social, economic and political crises onto a problem of crime. For this last group, policing the crisis remained an important point of reference.

3.6 Activity: Mugging and the media

In 1978 Stuart Hall and his co-writers (Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke and Brian Roberts) published Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order, in which they argued that the growth in media coverage of crime in Britain in the early 1970s contributed to a widespread belief that there was a crisis in society, in particular to do with the sudden rise of the ‘mugger’ or street robber. The video with Professor Stuart Hall which you are now going to watch is introduced by one of Hall’s co-authors, Professor John Clarke.

Activity 9

As you watch the video, jot down, in your own words, some brief notes in response to the questions below. It might be helpful to watch the video all the way through once and to then watch each section in turn, pausing to make notes in response to the questions.

Transcript: The media and social disorder

1. In the first section of the clip, according to Stuart Hall why do the media use labels ?

Discussion

According to Stuart Hall, the media uses labels to:

- simplify things in order to make sense of complex phenomena

- focus people’s attention on something

- mobilise strong feelings

- cluster stories together even if they don’t really belong together

- create a news spiral – coverage is increased by clustering stories together

2. In the second section, ‘Crime statistics and news values’, why does Stuart Hall question the claim that crime statistics are hard facts?

Discussion

Stuart Hall casts doubt on the claim that statistics are hard facts by showing how the ways in which crime statistics are defined and interpreted can alter the data. For example, there is no published figure for muggings until 1972, although the figures for muggings are then projected back to 1968. The 1968 figure, however, represents crimes which were not previously defined as muggings and probably included crimes previously included under other robbery categories. According to Hall, this shows how the label of ‘mugging’, which is not even a crime in law, has served to cluster together crimes which may not really belong together.

3. In the third section, ‘From definers to the media’, how does Stuart Hall define an ‘amplification spiral’ and what is the role of the media within it?

Discussion

Stuart Hall describes the amplification spiral in the following way:

- Images in the media sensitise the public to mugging.

- The public becomes anxious and might express their fears through writing letters to the media.

- Judges refer to this public anxiety, which is then reflected in longer sentences.

- Longer sentences in turn become a news story which feeds public anxiety further.

The media, according to Hall, are not outside this amplification spiral but form an important part of it, because the media are the link between the primary definers (judges, police, politicians), the public and the news.

4. Finally, why does John Clarke argue that the work of Stuart Hall on ‘policing the crisis’ is still relevant today?

Discussion

John Clarke argues that the media and the primary definers play similar roles today as they did in the 1970s. The labels might change – benefit scroungers or rioters rather than muggers – but the processes of social control remain.

3.7 Summary

This section has explored how sociologists have studied the social reactions to disorderly behaviour, beginning from Becker’s view that ‘deviance’ is not an intrinsic property of an act, but a label applied to it. This view enables the study of how:

- some behaviours (and some types of people) come to be defined and labelled as deviant

- the media play a role in defining deviance and creating social anxiety or moral panics about some types of behaviour (and some types of people)

- agencies of social control (the police and the criminal justice system) may act in ways that concentrate on some types of people rather than others

- crime and the fear of crime may play a significant role in politics, including as a displacement of other problems and crises.

4 Similarities and differences between the approaches

The differences between the psychological approach and the sociological approach are very significant. But the two approaches also share some important things in common.

Activity 10

Can you think of any similarities between these two approaches?

Discussion

We have identified these common features of the approaches:

- They share a basic social science approach in which evidence (of different sorts) is assessed and analysed.

- They share a commitment to treating social phenomena as capable of being analysed and explained systematically.

- They both involve the use of theories (structured explanations) and concepts (key explanatory ideas) in the construction of an analysis and argument.

- They understand that presenting an analysis is also to be engaged in an argument (with other approaches and explanations).

- They share a concern with the problem of understanding contemporary social issues that are seen as being of considerable public importance. In particular, they view delinquency/deviance/disorder as posing vital questions for social science study.

- Both approaches more often focus on the behaviour of men, rather than women.

- Both approaches construct analyses using evidence (even if the evidence they use is very different).

Activity 11

Given the way the course is structured, it is probably easier to draw out points of difference between the two approaches. Can you think of any differences?

Discussion

The differences between the psychological approach and the sociological approach might include:

- They start from different questions (explaining delinquency versus explaining social control).

- Psychological approaches see deviancy as originating from the individual, whereas social control theorists see deviancy as originating from social control processes and the creation of rules that classify certain behaviours (and certain people) as being deviant.

- The psychological approach investigates risk factors for delinquency, such as personality, family background and poverty. By contrast, social control theorists focus on the processes involved for those labelled as being deviant, whether they live up to the label and follow a deviant career.

- Psychologists assume there are sets of behaviour that are deviant or classified as crimes, and people may have long-term or short-term risk factors to commit crimes. However, social control theorists are interested in how the definition of deviancy may change over time, as societal norms change. Studying control provides an understanding of social order, its rules and norms.

- The psychological approach assumes that there is a group of people who are deviant or commit crimes, compared to a ‘normal’ group. In contrast, social control analysts suggest that it is not the people who are deviant, rather they have been labelled as deviant, and make a distinction between those labelled as committing deviant behaviour or those who are labelled as being in ‘high spirits’.

- The majority of psychological research has tended to focus on white, working-class males and to develop theories from their findings. In contrast, the social control approach suggests that children from higher income families may be as likely to commit deviancy or crime (from vandalism, truancy and drug use through to corporate crime), although working-class youth and those from minority ethnic groups may be more likely to be arrested or stopped and searched.

- According to the ICAP theory, if some people are more at risk of committing crime, then programmes can be developed to try and minimise them and prevent deviancy or crime. In social control studies, we learn about social order by studying the process of making and applying rules. Such studies tell us how society works – especially in how it views and tries to control disorder.

- They tend to use different methods, and as a result, use different sorts of evidence.

- The approaches make use of and develop different theories, and perhaps have different views of the uses of social science.

Let us just return to the first point of difference here – that they start from different questions – because many of the other differences flow from this starting point.

4.1 The psychological approach

For those studying the causes of crime, the organising question is: how can delinquent/deviant behaviour be explained? This leads to a search for explanatory factors: conditions, characteristics, processes or relationships. It orients such work towards some types of evidence: questionnaire data; statistical comparisons (between a deviant group and a normal or ‘control’ group); longitudinal studies (following a set of individuals over a long period). It also leads to certain types of theory: theories that develop causal explanations between the critical factor(s) and the delinquent/deviant behaviour. Such theories might be pitched at different levels of analysis: the micro-level of individual personality and circumstance; the meso-level of immediate conditions and relationships: the family, the neighbourhood, the group; and the macro-level of the wider social, economic and political structures.

4.2 The sociological approach

In contrast, the social control approach starts from very different questions:

- How does some behaviour come to be defined as deviant?

- How do some people come to be labelled as deviant?

- What do such processes tell us about social order and the way it is made and remade?

This leads to a search for explanatory factors:

- Who gets to define what is normal and deviant?

- What explains why some people are labelled and not others?

- What social purposes are at stake in the processes of social control?

- Why are societies prone to moments of ‘moral panic’?

This search orients social control studies to some types of evidence: historical studies of law making; statistical studies of legal processing (for example, stop and search processes, prosecution decisions); the social biases of social control agencies; analyses of media content; studies of the relationship between politics and social control. But here, too, social scientists work at different levels of analysis: at the micro-level they may study interactions between police officers and ‘suspects’; at the meso-level, they may investigate how organisations make social order – looking at police culture, for example; and at the macro-level, they investigate why some things are turned into crimes; or why some sorts of behaviour (or people) become a problem at a specific place and time. But the starting points – the questions that begin the process of inquiry – really do make a major difference. We hope this course has revealed why this matters – and how both the approaches contribute something distinctive to an understanding of social order – and disorder.

5 Conclusion

In this course, you studied the issue of juvenile delinquency and how this youthful misbehaviour can be studied. The authors focused on two main approaches, each of which starts with a different question: one approach tries to identify the causes of delinquency to answer the question of what makes some individuals but not others behave badly; the other approach changes the question to focus on why and how some behaviours but not others become defined as delinquent. Answer the following questions in Activity 12 to develop your understanding of different aspects of this course.

Activity 12

a.

Behaviour that breaks the current laws of the country

b.

Status offences such as underage drinking or truanting from school

c.

Behaviour that breaks social norms or expectations

The correct answers are a, b and c.

Discussion

Juvenile delinquency can include all of those aspects listed above. It is a complex term: it is not static but can change over time in response to changing expectations of what is acceptable. Who gets to define what counts as delinquency is also important to consider.

a.

There are three personality dimensions: extroversion, neuroticism and psychoticism.

b.

Personality has a biological basis.

c.

Criminals score at the higher end of each of Eysencks’s scales in comparison to non-offenders.

d.

Certain risk factors, such as family background or low intelligence, can be identified which are associated with the potential for criminal or deviant behaviour.

e.

The link between personality and deviant or criminal behaviour was due to differences in learning during childhood.

The correct answers are a, b, c and e.

Discussion

- All of the above claims are part of Eysenck’s theory apart from the claim that it is possible to identify certain risk factors associated with the potential for criminal or deviant behaviour. This claim, by contrast, is associated with the Cambridge Study of Delinquent Development and Farrington’s Cognitive Antisocial Potential Theory.

- Eysenck began by identifying two personality dimensions – extraversion and neuroticism – but later added a third dimension, psychoticism.

- He claimed there was a biological basis for personality and people’s score on the different scales related to levels of arousal from the nervous system.

- He argued that criminals would score at the higher end of each of the scales in comparison to offenders. Those who scored higher found it more difficult to learn right and wrong behaviours during childhood thereby demonstrating a link between personality and deviant or criminal behaviour.

3. Which of the following concepts did each of the authors below use in their theories?

Moral panics

Stanley Cohen

Labelling

Howard Becker

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 2 items in each list.

Moral panics

Labelling

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Stanley Cohen

b.Howard Becker

- 1 = a,

- 2 = b

Discussion

Cohen used the concept ‘moral panic’ to show how certain behaviours or groups of people become defined as a threat to society by the mass media and figures of authority such as judges, police offices and politicians. A moral panic is a press campaign, driven by the media and authority figures, which labels negatively a section of society.

Howard Becker used the concept of labelling to show that:

- The only difference between a ‘normal’ group and a ‘deviant’ group was that the latter had been ‘labelled’ as deviant/criminal. This meant that some in the normal group might have done exactly the same things but had simply not been labelled as deviant while some in the deviant group might have been wrongly labelled.