3.4 Media and moral panics

The sociologist Stan Cohen published a widely used study (1972) of the social reaction to fights between Mods and Rockers (two rival youth subcultures) at English seaside towns during the 1960s. Cohen analysed the media’s reporting of these events and found them to be highly dramatised, turning rather banal events into sensational – and sensationalised – news. He pointed to the ways in which these groups of young people were demonised, and viewed as posing a major threat to the stability of social order in the UK. He called this process of demonisation the creation of ‘folk devils’ – invented figures onto whom a whole variety of problems, dangers and anxieties could be projected.

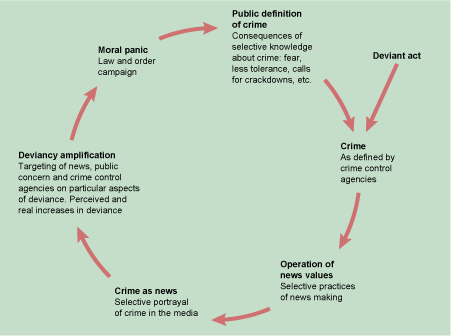

At the heart of this process was a relationship between the mass media and figures of authority (judges and magistrates, senior police officers, politicians and others whom Cohen described as ‘moral entrepreneurs’ who saw an opportunity to speak out about the ‘state of the nation’ and the dangers posed by such young people). The mass media – print journalism, radio and television – provided the forum in which figures of authority could pass judgement, issue dire warnings and demand strong action. Cohen described this process as the creation of a moral panic, which he described as taking place when a ‘condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests’ (1972, p. 9). The important point here is the idea of ‘become defined as’. Cohen’s study suggests that the fights between Mods and Rockers were treated disproportionately by the media and those in authority. In the process, they had other concerns and social anxieties projected onto them. The ‘definition of the situation’ turned the Mods and Rockers into a major threat to the future of the social order – and they were treated according to that definition (a combination of public condemnation, heavy policing and tough sentencing). Finally, Cohen suggests that the creation of folk devils and the development of moral panics – although certainly irrational and disproportionate – served some social interests. The Mods and Rockers gave a platform for ‘moral entrepreneurs’ to tell stories about the state of the nation and its young people; for judges and magistrates to ‘defend the public’ through tough sentencing; and for senior police officers to demand more resources in order to respond to this new threat to society. And, just as Becker suggested, the process of labelling had effects on those being labelled – such that Mods and Rockers tried to live up to their new public reputations: learning to perform their roles in the drama.

Cohen used the idea of a ‘deviancy amplification spiral’ in which the media’s dramatisation of particular events increased their visibility and the anxieties about them, such that campaigns by police, politicians, the judiciary and representatives of ‘concerned citizens’ increased the public focus on these actions and the ‘folk devils’ held responsible for them.

In the conclusion to the book, Cohen argued that this distinctive set of dynamics – identifying folk devils, dramatising them as other and dangerous, creating a moral panic about the threat that they pose to the social order, and amplifying the reaction to them (tougher policing, tougher sentences, and so on) – would recur:

More moral panics will be generated and other, as yet nameless, folk devils will be created … our society as presently structured will continue to generate problems for some of its members … and then condemn whatever solution these groups find.