6.1 Government expenditure (1)

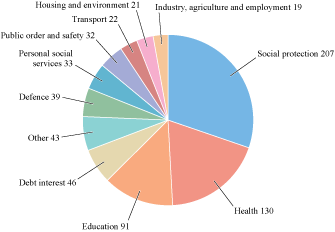

In modern capitalist economies, the public sector plays a key role. In the UK, total government expenditure was forecast to be £683 billion in the financial year 2012–13, which is 43.4% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (HM Treasury, 2012). Government activities range across all spheres of the economy, from the provision of social protection (such as benefits and pensions) to health, transport and defence. A breakdown of government spending is provided in Figure 13. Social protection is clearly the largest category, with health and education the next largest categories.

Social protection includes the provision of transfer payments, where there is a transfer from the government to individuals that is not made in return for any services. Old-age pensions and unemployment benefit are examples of transfer payments. If, for example, a refuse collector becomes unemployed and receives unemployment benefit, this benefit is a transfer payment, since he is providing no direct service. By contrast, if the refuse collector is in work and paid a wage by the government, that is government spending on the service of emptying bins.

As you will see in the analysis that follows, some economists and policymakers may regard government expenditure as unproductive and wasteful, a drain on the wealth-creating private sector, even when it takes the form of expenditure on goods and services. For Keynes, however, government expenditure represents a powerful lever for intervention when the private sector fails to generate sufficient demand.

Keynes formulated his ideas during the 1920s, making a number of attempts to persuade the UK government to increase its expenditure in order to boost aggregate demand. Although the wartime British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, had promised that there would be ‘jobs for the boys’ when soldiers came home after the First World War, this did not materialise. High unemployment in the 1920s led to the decline of the Liberal Party, of which Lloyd George was the leader, and its replacement by James Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour Party as the main alternative to the Conservatives – a position from which the Liberal Party (calling itself the Liberal Democrats at the time of writing) has never recovered.

In one final push, in the 1929 General Election, Lloyd George tried to regain his supremacy over the ‘spectre’ of socialism. Under his auspices, the Liberal Party published a pamphlet entitled ‘We can conquer unemployment’. He also marshalled the support of Keynes to develop his party’s manifesto. In his address to Liberal candidates on 1 March 1929, Lloyd George pledged: ‘If the nation entrusts the Liberal Party at the next General Election with the responsibilities of government, we are ready with schemes of work which we can put immediately into operation, work of a kind which is not merely useful in itself but essential to the well-being of the nation’ (Keynes, 1972, p. 88).

The Conservative-dominated press rubbished these claims as the fantasies of a Welsh windbag, being far too optimistic and not based on common sense. Keynes piled in, in a pamphlet entitled ‘Can Lloyd George do it?’, written with a politician, Hubert Henderson. This aimed to supplement and to answer criticisms of the Liberal Party pamphlet mentioned above. Keynes wrote:

The Liberal Policy is one of plain common sense. The Conservative belief that there is some law of nature which prevents men from being employed, that it is ‘rash’ to employ men, and that it is financially ‘sound’ to maintain a tenth of the population in idleness for an indefinite period, is crazily improbable – the sort of thing which no man could believe who had not had his head fuddled with nonsense for years and years.

In answer to the objections raised by the then Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, Keynes observed: ‘Mr Baldwin and his colleagues are not more capable of expounding the true economic science of the matter than they would be of explaining to you the latest propositions of Einstein’ (Keynes, 1972, p. 91).