5.3 Statistical discrimination

5.3.1 Investment in education and training

Human capital theory has been used to show how investments in education and training lead to higher levels of earning. One reason why education and training are referred to as investments is because their benefits accrue over time and because training early in a career leads to higher earnings over the rest of an individual's working life. An important consideration, therefore, in the decision about whether to invest in additional human capital is the potential length of working life over which the benefits will be received. This would suggest that if certain groups of workers – most notably married women with family responsibilities – expect to have interruptions in their careers they will invest less time and energy in acquiring human capital. They thus face lower earnings as a result of having less training and lower skills. Because women themselves choose not to invest in skills and training, their lower earnings would not represent discrimination according to the definition used in this course. Of course, it could be argued that some women decide to focus on their family and domestic activities precisely because they perceive poor career prospects for women, prospects which are themselves a reflection of discrimination. This is an example of reverse causation.

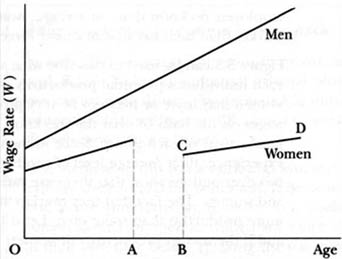

The impact that career interruptions can have on the earnings profile of women can be shown using Figure 3. We shall initially assume that men come to the labour market with a certain amount of human capital and this determines their initial earnings. Subsequent training and promotion then result in their earnings increasing each year which is reflected in an upward sloping age-earnings profile (this shows how an individual's or group of individuals' earnings change over time). On the other hand, we shall also initially assume that all women expect to drop out of the labour force because of family responsibilities and, as a result, undertake less education and training before entering the labour market.

Hence, their age-earnings profile is lower than that for men. For example, women may choose education and training courses, such as those providing clerical, secretarial or nursing skills, that enable them to enter occupations in which breaks from work incur the smallest penalty. Once they enter these occupations they receive less training than men because expected career interruptions reduce the returns from such investments and consequently their earnings profile rises at a lower rate than that for men. This is shown by the segment of the age-earnings profile up to age A. At age A, we assume that women drop out of the labour force and that when they enter the labour market again at age B, depreciation of their skills has resulted in a reduction in their potential earnings. In addition, the interruption has also resulted in a loss of seniority which has depressed their scope for earnings growth even further. This is shown by the segment CD.

Human capital theory therefore predicts that women will earn less than men because they do not expect to spend as long in the labour force. Intermittent work histories will also influence career choice. Fewer women will pursue skilled occupations and the professions, and more will be attracted to those jobs that enable them to more easily combine family responsibilities and labour market activity. Women are less likely to be promoted to higher level grades where these involve additional training since the monetary gains to the firm will, on average, be lower for women. The result is that promotions will be biased in favour of men.

We have, of course, made some very strong assumptions in painting the above picture of participation and occupational choice. Women now account for about half the total UK workforce (though women as a whole work shorter hours in employed labour and a larger proportion are part-time) and many women have as strong a commitment to their careers as men. The ability to combine family responsibilities and a career depends upon a number of different factors, not least of which will be the nature of the job and the availability and cost of such things as crèche and childcare facilities.