2.3 Europe as a ‘non-other’

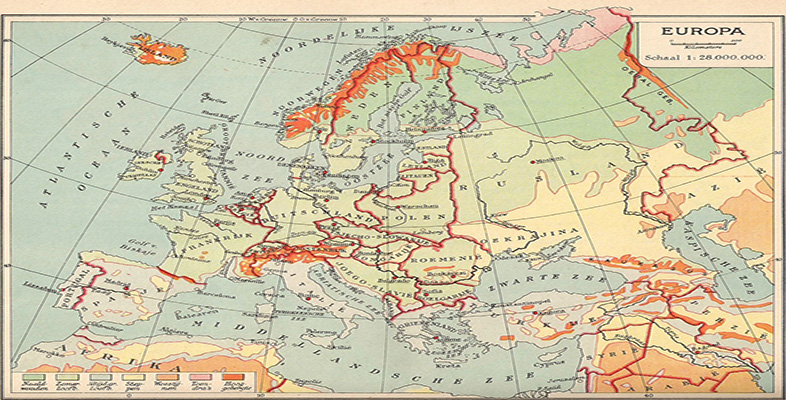

The idea of ‘otherness’ has always been a strong component in the formation of any European identity and it is a division that has, paradoxically, run as much through geographical Europe and its societies as it has demarcated Europe from supposedly alien, external civilizations. ‘Europeanness’, like other collective identities, has faced two kinds of others: those fully external to it and those located within. One of the problems surrounding the development of a modern European identity may be that the external other has often been distant and relatively weak, so directing attention to internal differences and encouraging tendencies to conflict within the European whole (Therborn, 1995, p.243). Definitions of Europe in terms of its system of values too, have rarely identified the same group of countries or geographical area. Peoples close to others on the continent, and even direct neighbours, have often been excluded from the European community because of an alien identity that has been projected on to them. Successive values have, indeed, been promoted as much to exclude certain regions, countries or powers – as well as certain groups within them – as to include others.

Early Europe as Christendom already contained significant religious minorities (Jews and Muslims) – and barely included the rural masses whose peasant status was closely linked with a ‘pagan’ (and thus non-Christian) outlook which presented a constant challenge to the consolidation of any regional Christian realm (Fletcher, 1998, Chapter 2). It could well be argued that the existence of such ‘others’ strengthened the emerging ‘European’ identity of an articulate elite and may well, indeed, have been a precondition for its development. The roots of modern sentiments of European superiority and colonial racism seem to lie deep in the early development of any common identity and were already linked at an early stage with the dealings of a Latin core with a greater European periphery (Bartlett, 1994, p.313). The strongly differentiated and historically rooted character of any European identity may well be one of its major features, and thus a prime source of the difficulties encountered in defining any contemporary system of European values. The fundamental nature of Europe over the long term may best be defined less by any commonality of values than by the persistence of division and conflict as sources of creative change (Malia, 1997, p.20).

The core area of European identity has also shifted over the centuries, and this has been linked with changing perceptions of who were the critical outsiders and major antagonists. For much of the early period the realm of Christian faith had been based on Constantinople and the eastern part of the Roman Empire rather than on the distant reaches of the west and north. The empire had already been divided into two parts for ease of administration in the third century AD as Goths and other ‘barbarians’ intensified their attacks. It was the eastern part, ruled from the capital founded by Emperor Constantine at the ancient settlement of Byzantium (and later transformed into modern Istanbul), that proved to be more stable and defensible than the portion ruled from Rome itself. But subsequent developments tended to identify the western variants of Catholicism and Protestantism as more authentically ‘European’ than the Orthodox faiths of the east and south.

The heartland of Latin Christendom was certainly more ‘European’ in its dynamism and capacity for sustained material and cultural development (Malia, 1997, pp.6–8). Russia in particular, although a Christian power for most of its five-hundred year existence as a state, has been distinguished for its persistent ‘otherness’ from a more authentic Europe. Russia was invariably portrayed as just having been tamed and civilized, and almost (yet never completely) ready for full participation in the European project. This has been the case once again since the collapse of communism and the end of the Soviet Union in 1991 (Neumann, 1999, p. 110). Similar tendencies were present in the values of the European civilization of the eighteenth century, as the nations of the developed west increasingly premised their superiority on the backwardness of other regions and ‘invented’ a barbaric eastern Europe to substantiate their claims (Wolff, 1994). In more recent times, after the Second World War, the Europe of the west (although strongly underwritten by the USA) was clearly regarded as more ‘European’ than the Soviet-dominated east, a view that supported the special role played by the EU and its predecessors in the region as a whole. Its economic success, sustained democracy and overall stability all strengthened the conception.

It is a view that clearly prevails in post-communist Europe and is one reason why, following the removal of the Iron Curtain, it still remains difficult to conceive of a broader-based European identity or a set of values that might sustain it. ‘Europe’ has become identified with the affluent stability of the western community, and the long-established traditions of violence and instability now seem distinctly un-European. It is a dimension of the new Europe of the 1990s that has been strongly reinforced by the successive conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. In the context of the 1999 Kosovo conflict, a new definition of Europe as ‘the place where tragedies don't take place’ was pertinently advanced by Susan Sontag (Observer, 16 May 1999). Developments in more than one of the former communist countries of eastern Europe constituted a major practical problem for EU leaders, as well as posing a challenge to any definition of Europe in terms of a coherent system of values (the problems involved in governing diversity are the subject of Module 4). Relations within Europe as a whole and between its constituent parts continue to create new fields of conflict as well as forging constructive links. War could be waged on Serbia precisely because ‘European values’ were being infringed in Europe itself, but it was also the importation of values of nationalism and ethnic collectivism into the Balkan peninsula and the very recent encouragement of national separatism throughout the former Yugoslavia in the name of democracy (a policy surely discredited enough by developments throughout Europe in the inter-war decades) that created the conditions under which such abuses could flourish.

Measures designed to achieve monetary union were, moreover, simultaneously being pushed through in the ‘core Europe’ of the EU precisely to strengthen the internal cohesion of the centre and protect it from surrounding instabilities. Non-EU countries were, of course, not part of this development, and the Balkans and large parts of post-Soviet Europe continue to remain both within and outside ‘Europe’. Such divisions and the particular uses made of formally ‘European’ values place further doubts on the idea of Europe as an inclusive value system of any sort. It has, therefore, been argued that any new Europe has to be imagined afresh in the context of the particular problems and challenges it faces at any one time, and constructed as a conscious plan of action rather than deduced from existing values. The idea of such ‘projects for Europe’ is not a new one, and similar proposals have been prominent in discussions about the future of the region since the shattering of so many European illusions in the First World War.

Summary

-

‘Europe’ clearly refers to a definite geographical area (although with some uncertainty around the edges), but as a broader idea Europe has also meant considerably more than this.

-

Uncertainties about the precise parameters of geographical Europe have been closely linked with important cultural contrasts and differences in social values.

-

A European identity emerged on the basis of the relatively unified Christendom of the late Middle Ages, and this became more explicitly ‘European’ as Christianity itself became more diverse.

-

An increasingly secular structure of values associated with civilization and various conceptions of progress became more differentiated in the nineteenth century; they gave rise to powerful nationalist currents and increasing rivalry between Europe's nation states.

-

The destructive outcome of nationalism in Europe and the increasingly violent political movements it engendered left doubts about the existence of any authentically European values.

-

As it has throughout history, modern European identity continues to be defined to a large extent by reference to non-European others, either internal or external, and the contemporary formation of a unified homogeneous ‘idea of Europe’ continues to emerge as a problematic process.