4 Debates on the development of Europe

Not unlike that of earlier conceptions, the new Europe of the early twenty-first century involves a somewhat loose idea of Europe as a geographical entity and a project of European development based on the pursuit and expansion of core values. Early Christian Europe had developed a self-awareness in terms of fundamental religious beliefs and pursued them within and beyond its original territorial base in a series of crusades and related initiatives; the more secular Europe that followed fostered a culture of multi-faceted superiority that transformed the face of the entire globe. The closely linked, though somewhat diverse, projects of post-1945 Europe have all involved the attempt to confront and transcend the tendencies of militarist nationalism that emerged in the nineteenth century. They differ from earlier visions in that they are primarily concerned with the nature of Europe itself and the inner dynamics of its future development. Modern ideas of Europe have increasingly been concerned with the development of conceptions of democratic coordination that will be both effective and sufficiently broad to encompass the wide range of national traditions and political preferences that are expressed in the countries involved.

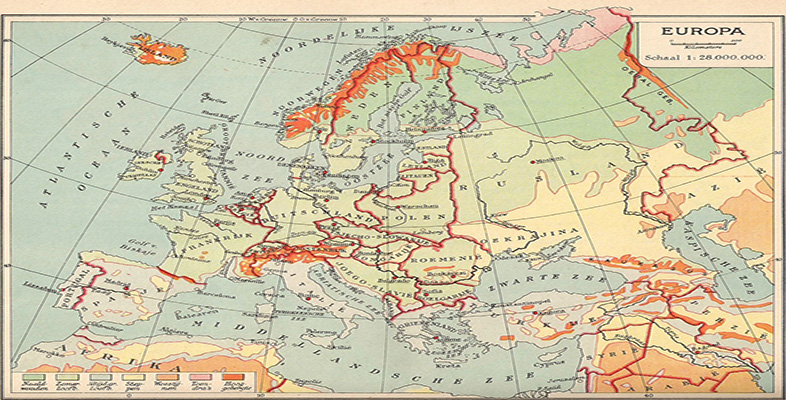

The considerable success that the EU achieved by the end of the 1980s in securing these objectives within its restricted western territory has now been followed by the challenge of defining and organising a broader, new Europe in which the post-communist countries of the east are again active members. The new global context and general dominance of liberal-democratic values represent a further dimension of this new European identity. The geographical dimensions of this new Europe have been in one way self-evident, in that the end of the Cold War division of the continent placed an older idea of Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals back on the agenda. But at the same time an even broader conception that took account of the realities of a more integrated world-system gained currency, in which a European system was understood to extend from Vancouver to Vladivostok (Story, 1993, p.509). It reflected the understanding that the civilization of North America stemmed directly from that of an older Europe, and had been carried forward in large part by people who had come directly from the old continent. Russia, too, reaffirmed a basic European identity as it embraced Western values and turned away from the communist mind-set that had placed it in direct opposition to the capitalist West.

Europe in this sense, defined once more with prime reference to its liberal and democratic values, could again be understood to embrace a large part of the entire globe – its two branches apparently meeting somewhere in the north Pacific. This, however, meant little more than the globalisation of European values and the spread of the respect for core human rights that had evolved over the centuries – a process by no means without severe setbacks – in the cultural centres of western civilization. A recognition of such values was already embodied in the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights issued soon after the UN's foundation. The end of communist rule in Europe and throughout the rest of the Soviet Union certainly extended the possibilities for political freedom in some European countries, but it hardly spelled the emergence of any new European civilization in a broader sense. As the problems of coordinating and developing the more traditional ‘regional’ Europe – now politically liberated but only partly democratised – have come to the surface and become more pressing, less is heard of this global Europe.

Continuing uncertainty within Europe as to what it stands for and who the institutions of the EU actually represent create major contemporary difficulties of definition. One of the fundamental problems in defining the contemporary new Europe has remained the lack of any shared identity, the absence of an agreed understanding of what Europe represents and what it exists for – in short, the weakness of Europe as a system of values. By the end of the 1990s few German, British or French people saw themselves as being primarily European, more (16 per cent) being found in France than in the other two countries. Substantial numbers in most countries saw themselves being European after a primary identification as citizens of the appropriate nation state. But a majority of Britons and Danes still did not acknowledge any European identity at all after twenty-six years’ formal membership of a European community. Satisfaction with EU membership, or its expectations, actually declined between 1973 and 1998 in the region as a whole, and fewer than half of all Britons and Italians believed that European integration had achieved much at all in the post-war period (Moïsi, 1999, pp.49–52).

Support for European integration and what were generally termed western values was, on the other hand, strong throughout former communist Europe and particularly in the more developed countries of east-central Europe that envisaged a rapid and relatively smooth passage into the EU. But commitment to such values began to decline in the post-communist area during the mid-1990s, too, as accession negotiations began to place major demands on the newly liberated countries. On the eastern margins of geographical Europe, Russia has traditionally been divided in its attitude to Europe between Westernisers and Slavophiles (Neumann, 1996, p.28). After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 this was reflected in an equivalent distinction between Atlanticist and Eurasianist perspectives. Opinion polls conducted in 1993 showed majority support in all groups making up the Russian elite for the Eurasianist perspective. As some analysts emphasised, this by no means represented a rejection of western perspectives (these were more firmly rooted in a ‘neo-anti-imperialist perspective’), but rather an eclectic outlook characteristic of an emerging centrist position (Zagorski, 1994, p.71). Nevertheless, they hardly indicated the flowering of any full European consciousness or the acceptance of overtly European values.

Views ‘from the Atlantic to the Urals’ tend to suggest, then, a widespread hesitancy and highly qualified commitment within the new Europe to anything that could be identified as a commonly agreed vision of Europe. This by no means erected any major obstacle to the pursuit of the project that has underpinned the new Europe of the 1990s:

-

a ‘deepening’ of the original west European Union in the pursuit of European Monetary Union; and

-

its ‘widening’ to include, in 2004, eight post-communist countries in east-central Europe, as well as Cyprus and Malta.

But the project remains subject to qualifications on both counts. Internal resistance to the extension of monetary union persists in the case of the UK and a few other countries, and there is no conviction that the structures of the EU can be extended to include the whole of geographical Europe in the foreseeable future.

The uncertainties that accompany the continuing pursuit of the project cannot be regarded with much surprise. The dismantling of the Iron Curtain and the end of a division of Europe enforced by global superpower rivalry could hardly have led in itself to the sudden emergence of any conceivable single or unified Europe in a meaningful sense. Indeed it has led to a delineation or resurgence of several traditional and diverse Europes in place of the increasingly unified western Europe that the Cold War division of the continent had allowed, to present itself as the modern variant of Europe tout court. In this sense the new Europe of the 1990s emerged less as one that is just one stage on from the modern, post-1945 capitalist democratic Europe of the west than a region that is more differentiated and reminiscent of earlier conceptions of coexisting and multiple Europes (Malia, 1997, p.10). It also harks back to the three historical regions of Europe – the west, east and an ‘intermediate’ eastern-central (see Szucs, 1988).