Debates on the development of Europe (continued)

Activity 5

Alongside the evident diversity in contemporary Europe itself there are clearly different views expressed on how Europe is developing and the kind of Europe we can expect to see emerging in coming years. The pieces by Dominique Moïsi, ‘Dreaming of Europe’ (Reading G), and Tony Judt, ‘Goodbye to all that?’ (Reading H), reflect such contrasting views of European development. Evidence from a recent Eurobarometer survey (Reading I) throws further light on some of the topics they discuss.

Now click here [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] to read the three pieces. Try to identify the main points they make. What are the three ‘fundamental challenges’ that Moïsi identifies, how does he see relations between the major states developing – and what sense do you make of his judgement? What are the more sceptical conclusions reached by Judt, and what precisely do you think Europe might or might not be saying goodbye to?

What do more recent survey results contribute to an understanding of the issues they raise? You can use the Eurobarometer material to develop your skills in understanding and analysing statistical, graphic and tabular data to test the generalisations and suggestions made by Moïsi and Judt in the light of recent EU developments. See if you can find evidence, for example:

-

to support the contention of Moïsi that a spectacular change in British attitudes to Europe was taking place during Tony Blair's tenure as prime minister;

-

to see if the UK population has developed any marked appreciation of British membership of the EU or enthusiasm for the proposed Constitution in comparative terms;

-

to evaluate the developing nature of the Franco-German relationship in terms of defence and security preferences and their support for common EU initiatives.

The fundamental challenges identified by Moïsi (1999) for the Europe of the 1990's are those of sovereignty, space and identity. Traditional notions of sovereignty have remained ambiguous in the wake of the Kosovo war, in that the sense of European ‘space’ is still problematic with the traditional questions about Russia and Turkey now raised in contemporary terms, while the idea of a common European identity seems to make some progress despite undoubted obstacles. Whether the ‘dream of Europe’ presents a convincing vision is, and will remain, debatable. To my mind, it seems to involve some questionable assumptions. Clearly some important changes have occurred, but it becomes increasingly difficult to share the view that a ‘spectacular change in attitudes and policy toward Europe has taken place in Tony Blair's Great Britain’ in the way suggested by Moïsi. Evidence presented in the article itself in terms of opinion surveys shows that the development of a European identity in Britain has been very limited. Furthermore, from the evidence gathered in 2004, the changes in British perceptions of the EU appear to be quite minimal. If 37 per cent of Britons thought that EU membership was a good thing in 1998, the percentage had risen by just one point to 38 in 2004 (European Commission, 2004). The British also perceived few benefits from EU membership, were mistrustful of its core institutions and showed scant enthusiasm for its proposed Constitution, coming just about last on all these scales.

Judt (1996) directs attention to the particular importance of the consequences of the end of communist rule in eastern Europe and the critical evolution in Franco-German relations that has taken place. He sees 1989 as bringing to an end a unique period in France's diplomatic history and facing Germany with rather too many problems in terms of European enlargement. Problems of economic growth, unemployment, immigration and a weakening welfare state all raise – in Judt's view – major problems for concerted European development and the growth of any broader European identity. ‘Europe’, he suggests, remains too large and too nebulous a concept to forge much of a convincing human community, and the traditional prominence of the European nation state in fact shows little sign of diminishing. It is time, in this view, to say goodbye to the strong idea of ‘Europe’ as a unified entity, which was able to take root and develop between 1945 and 1989 due to the conjunction of a particular set of conditions.

But here, too, recent developments might suggest a rather different perspective. If Moïsi may be over-optimistic about British sentiments for Europe, Judt may see too many problems inherent in the changing Franco-German relationship. With the launch of the euro in 1999, it can certainly be argued that relations between France and Germany have strengthened and a growing consensus seems to be emerging between their leaders about the future of the developing European framework. The common position taken by the two countries on the Iraq war has also strengthened their alliance within the EU. Public sentiments have also undergone a radical shift, and in a rather different direction from that seen in the UK. In 1992, just after the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty, only 45 per cent of a French sample declared themselves in favour of rapid European integration; in 2000 as many as 70 per cent opted for an equivalent policy, and 59 per cent were enthusiastic or favourable to further EU development compared with 41 per cent opposed to it or sceptical (Liberation, 26 June 2000). Support for a common defence and security policy has been quite high, at 78 per cent, within the EU as a whole, but it is particularly high in Germany (87 per cent in 2004) and 81 per cent in France, in contrast to 60 per cent in the UK (European Commission, 2004).

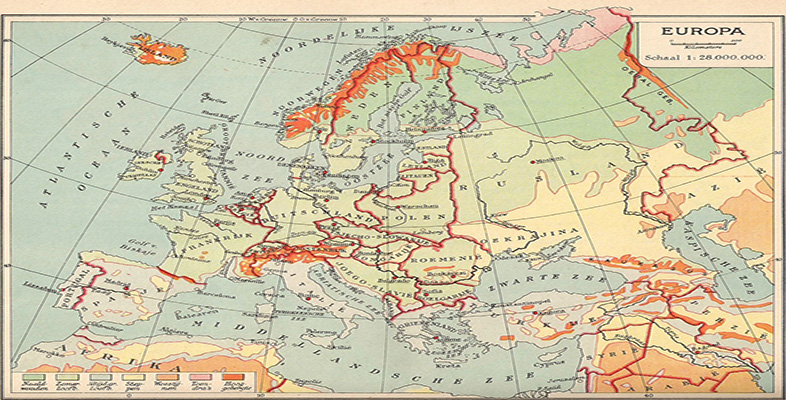

Precisely how Europe is best defined at the beginning of the twentieth-first century, and what prospects it has for further development, must therefore remain the subject of considerable debate. Traditional uncertainties about the geographical extent of Europe, the core values it may be understood to embody, and doubts about the commitment of many of the individuals, groups and nations that live there to any shared identity, remain. As the various European Communities founded in the 1950s developed and expanded to form a broader European Union in the 1990s, they have increasingly echoed these traditional uncertainties about what and where Europe is. This course will provide you with extensive material to explore these issues further and help you develop and clarify your own opinions.

We can nevertheless at least begin with certain observations about post-1945 Europe and the major developments that have occurred. Clear residues of the new project for Europe evolved in the middle of the twentieth century have remained, and certain achievements have held firm. There is still little dissension from the original post-1945 project for a Europe no longer led into war by Franco-German enmity or more general national rivalries.

Activity 6

It is now time to study ‘Europe in the Twenty-First Century’. The contributors are:

-

Robert Bideleux, Reader in Politics, University of Swansea

-

Mark Pittaway, Lecturer in European Studies, Open University

-

Hugh Starkey, Staff Tutor for Languages, Open University.

The programme is designed to explore three different areas:

-

questions of European identity;

-

ideas of what Europe currently is and what it might become; and

-

the relationship of different ideas of Europe to the evolving EU.

Spend some time considering (or reconsidering) these issues yourself, and jot down some answers to the questions they raise. Then listen to the discussion by clicking on the links below.

Transcript: Audio 1

Transcript: Audio 2

Transcript: Audio 3

Transcript: Audio 4

Transcript: Audio 5

I introduce the discussion by asking contributors to give their own answer to the question posed by Seton-Watson and discussed at the beginning of this course: What is Europe? Where is Europe? You may like to use this opportunity to confirm and consolidate your understanding of the material you have studied in this course so far by constructing your own answer to these fundamental questions. Now compare your answer with those of the contributors on the audio files. How do their answers differ? How do they compare with your views on the nature of twenty-first century Europe? The contributors go on to raise questions about the conditions for European unity and current prospects for the ‘European project’ as originally conceived in the years immediately following 1945.

At least part of any project for Europe at the beginning of the twenty-first century will be to manage the conflicts and diversity of modern Europe in ways that are equally successful in avoiding general warfare. Although significantly differentiated, much of the new Europe is also involved in a broad project of integration for which the main points of reference are to be found in the process of EU enlargement, as well as the changing framework and processes of evolution within the EU itself. A whole range of perspectives and opinions have been brought to bear on these processes. This leaves the new Europe of the early twenty-first century defined as much by what differentiates it, as by any principle of integration. But it does at least suggest some perspective of coordinated development that maintains the principle of peaceful evolution on which the growing community of Europe has been based since 1945.

Summary

-

Earlier forms of European identity were characterised by sets of values and projects which involved their promotion beyond the European homeland.

-

The focus of developments in contemporary Europe is more inner-directed and places greater emphasis on relations between its constituent parts.

-

The new Europe of the early twenty-first century is less sure of any shared identity and requires greater acceptance of a more differentiated region committed to the avoidance of military and other forms of violent conflict.