5.4 Inclusion and exclusion

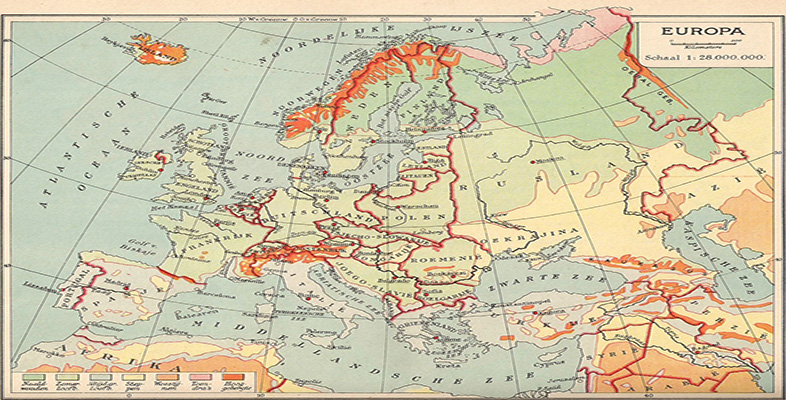

Contemporary Europe is, like that of earlier times, divided on several counts and reflects the continuing existence of several major identities. Individuals and groups invariably have several, overlapping or nested, identities at the same time. But there is also a hierarchy of different identities, with some groups having preferential access to particular European values and resources and others being partly or wholly excluded from them. Contemporary patterns of inclusion and exclusion refer partly to physical location, but elements of social ranking are also closely involved. Any geographical definition of Europe obviously excludes territories that lie outside its designated area. Africa and Asia have been distinguished from Europe since ancient times, but were ‘excluded’ only in the sense that they and their peoples belonged somewhere else. Geographical marginality with regard to contemporary Europe now has strong economic, political and social connotations as well. Ambiguities currently exist in this sense with particular regard to a number of Europe's border areas such as Turkey and north Africa, whose development in recent times has been closely bound up with that of the European continent and with whom economic and security links have been particularly strong. The inhabitants of such border-lands are also represented within Europe by major immigrant communities. Yet more have sought entry and residential rights and feel excluded when these are denied, although this is a status shared with many other potential immigrants from other parts of the globe. Turkey, in particular, has long sought admission to the EU and asserted a national claim to membership and European identity, and its refusal has provided a basis for growing sentiments of exclusion. In fact, decisions taken at the Helsinki EU Conference in December 1999 endorsed Turkey's long-term aims for membership and its application has been taken far more seriously in recent years.

But far more is involved here than the exclusion of border areas and the people who live in them by drawing boundaries around a geographical Europe. At issue is also the definition of a European identity by reference to certain values (in so far as they can be agreed upon), an area in which religious attitudes and racism often play a major part. Perhaps even more important is the question of who has access to Europe's diverse resources and the material advantages associated with its well-developed social and economic infrastructure. Lines of inclusion and exclusion also exist within Europe and may be drawn between different regions, national, ethnic and socio-economic groups – and on such bases often exclude numerous categories on all these counts at the same time. This has long been part of the European experience. The core Europe of the north-west of the continent has traditionally been distinct from a poorer south and east, which was subject to contrasting cultural influences and held a different religious faith or form of organisation. Distinct ethnic, socio-economic or class groups occupied different positions in this respect – as, indeed, they also did within the area of any ‘core Europe’ itself.

To this extent the idea of a fully inclusive Europe may be an illusion, in the sense that any game played to the end also involves both winners and losers. An emphasis on the different status of minority groups within a greater European whole may be a major mechanism that helps confirm the identity of the majority and strengthen the integration of Europe as the regional whole. Such examples range from the early persecution of Jews and Muslims in early modern Europe (at the same time as a distinctly European identity began to emerge) to the affirmation of distinctively ‘European’ values in the context of the NATO war on Serbia in association with the Kosovo crisis. But some developments also point to the possible emergence of a new situation in this sense. One important characteristic of the new situation with the end of the Cold War is that Europe as a whole is now more open to a stronger flow of internal influences and diverse forms of communication, and thus a stronger pull from an increasingly integrated EU core.

The more intensively governed EU, but one formally organised on inclusive rather than exclusive principles, is better suited for operating as a stable centre for the region. It may exercise an overall integrative pull and moderate, if not abolish, at least some aspects of exclusion. The further development of the EU's ‘cosmopolitan’ legal order may have distinct advantages in this respect over the nation-based provisions of established state legislation (Bideleux, 1999, p.33). Rather than developing as an exclusive European union, the EU also has the capacity to evolve as a Union of Europe, a prospect that may give more substance to the claim accepted and publicised by the Economist (23 October 1999) that it is no longer propagandist or even contentious ‘to speak of the European Union as synonymous with its continent’.

Summary

In this section we have reiterated and developed our main themes in relation to recent European developments:

-

unity and diversity

-

conflict and consensus

-

tradition and transformation

-

inclusion and exclusion.