6.3 Shopping with ‘vouchers’

Activity 5

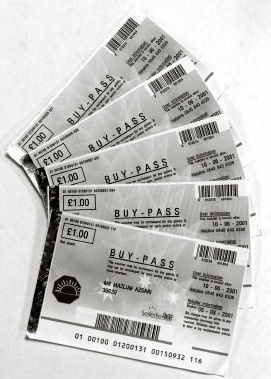

The advice given to young asylum seekers, reproduced here as Extract 4, describes how the system of vouchers (see Figure 4) operated before it was discontinued in 2002 (other details of the scheme are given in Table 1). How might this have shaped their personal lives?

Extract 4: ‘How do I buy food and other everyday items?’

If you are being supported by NASS, you will receive vouchers so that you can buy food and essential everyday items. These vouchers are issued by a company called Sodexho. You will probably receive emergency vouchers when you first arrive, but later you will have to collect them each week from a Crown (main) post office near to where you are living.

You can use the vouchers only at selected shops. Your landlord can tell you the names and addresses of these shops in your area. Alternatively, look for shops displaying the Sodexho BUY-PASS symbol in their window. You will also receive £10 cash each week that you can use for travel costs and for purchases from any shop.

Shops will not be able to give you change from a voucher so make sure you get enough low value vouchers (they are available in amounts down to 50 pence) and try to spend up to the full amount.

Discussion

The advice did not explain that the total value of the vouchers was set at 70 per cent of income support, nor that vouchers, unlike other social security benefits, did not entitle people to other benefits or services such as reduced admission charges.

While shopping, an activity that most of us carry out automatically, asylum seekers were constructed as ‘other’:

I feel we are marked in red because everyone knows we are refugees when we do our shopping by voucher. We feel humiliated at the checkout because when we give our vouchers, the cashier's attitude is usually really bad. Usually, when they tell us the total, they won't let us go back to pick up something for the change … Other customers who are in the queue behind us … often look at us in a very bad way, like: ‘Look at this asylum seeker, they are here, they are buying things with vouchers and they are holding us up.’ We try to be very fast and sometimes we end up making mistakes at the cash desk.

(Fatma, quoted by Gillan, 2001, p. 41)

This is a graphic illustration of the idea within Foucauldian post-structuralism that power resides not only in the state, but is dispersed throughout society through a range of human interactions and sets of relationships. In this instance, the ‘power to humiliate sits behind the till’ (Gillan, 2001, p. 41).

The policy was criticised by all organisations involved with asylum seekers, by many trade unions and the British Medical Association, and in an Audit Commission Report (2000), for being inhumane and stigmatising as well as bureaucratic and inefficient. In October 2001 the government agreed to phase out the scheme, but refused to return to providing cash benefits. Instead, asylum seekers would be housed in new reception and detention centres as these became available.

The 2002 Act further limited the access of asylum seekers to welfare, with even this limited support ending when they gained refugee status. Under Section 55, support was only available for those who applied for asylum ‘as soon as reasonably practicable’ after arrival in the UK, even though 65 per cent of people who received positive decisions had made so-called ‘in-country’ claims (Refugee Council press release, 19 February 2003). Refugee, human rights and homelessness organisations warned that it would leave ‘in-country’ asylum applicants literally destitute of the right to food or shelter. In contrast, the Home Office believed that ‘if they have been staying off the streets and managing for the weeks, months or years before they claimed asylum, then there's no reason why they should not continue to do so’ (Prasad, 2003, p. 2). The way the policy was administered resulted in ‘people … being refused support despite applying within days, sometimes minutes, of arriving in Scotland. Refugees ended up having to sleep rough and go hungry simply because they were traumatised, did not know the procedures or spoke no English’ (Scottish Refugee Council, 2003, p. 1).

Here we have an example of the way in which such policies and practices are contested, in this case by voluntary organisations. In March 2003, following legal action taken by the Refugee Council and other organisations, the Appeal Court ruled that the implementation of Section 55 was unreasonable (Refugee Council, 2003a). Nevertheless, one newspaper reported that ‘huddles of asylum seekers have begun visibly sleeping rough in central and south London … They have had letters from the government denying them support, in effect leaving them on the street, where they have been setting up permanent “homes” – gathering cardboard boxes’ (The Guardian, 18 August 2003, p. 7).

The 2002 Act also introduced the development of a new type of large accommodation centre, which because of its size (housing 750 people), was to be sited in rural areas, in contrast to the original dispersal ‘cluster areas’. Asylum seekers would only receive a small cash allowance, forcing them to stay at the centre for food and lodging, thus denying them such everyday practices as shopping and cooking. For the first time children were to be removed from mainstream schooling and educated within the centres.

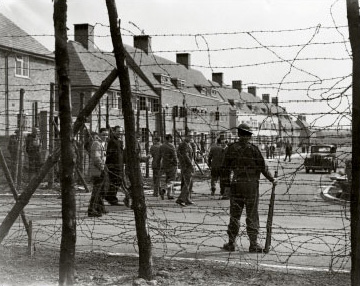

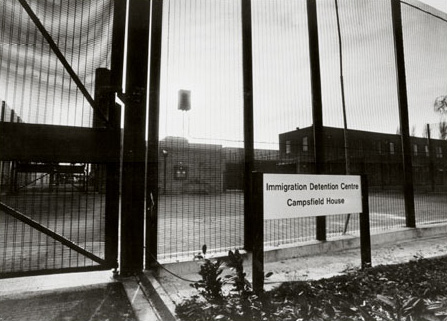

Refugee organisations argued that the Act sought to maintain high levels of monitoring and surveillance of asylum seekers, through a system of induction, accommodation and detention centres. They feared that accommodation centres could easily become locked detention centres (see Figures 7 and 8 for a historical comparison), and that they would ‘extend social division by ensuring that asylum seekers are effectively segregated from mainstream society’ and ‘become inevitable targets for racist attacks with barbed wire and security guards becoming a feature of these centres’ (Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, 2002, p. 4). Many local communities campaigned against such centres in their areas, ‘gripped by what … [the] residents admit is “a fear of the unknown” … They envisage men wandering their streets, skulking. They talk of threats to their children, of locking their doors, of terrorists. They admit they have no evidence for any of this’ (The Guardian, 6 February 2003, p. 11). Despite this opposition from refugee organisations and local communities, the Home Secretary was determined to press ahead with the centres, as they would ‘ensure the application process is speeded up … he also insists that the centres will ensure applicants do not drift away’ (The Guardian, 20 August 2003, p. 9).