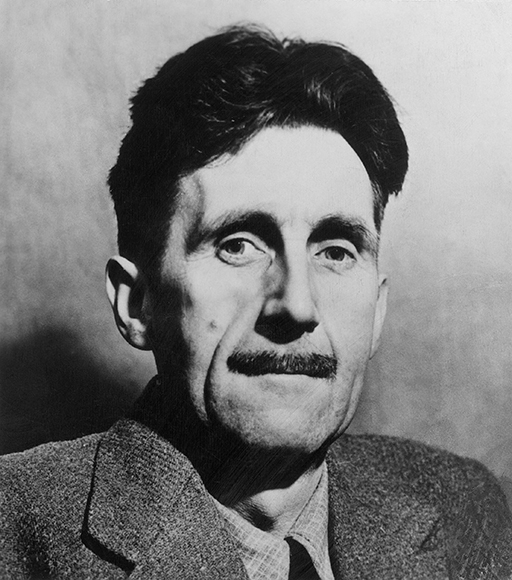

2.1 Orwell and socialism

What lay behind Orwell’s socialism? Orwell’s ‘conversion’ to (democratic) socialism dated from the mid-1930s and was prompted, in large part, by his investigation into the poverty and living conditions of the northern working class (a commissioned work of reportage published, in 1936, as The Road to Wigan Pier). Britain, in Orwell’s view, was a country governed by the rich and ridden with outdated class privileges. He likened Britain to ‘a family with the wrong members in control’ (Orwell, 1941, p.35). For Orwell, socialism was about addressing social and economic injustices and improving the lives of ordinary people. Orwell had little (if any) interest in political theory itself. He was suspicious of ideology, which in the wrong hands could become what he famously called ‘smelly little orthodoxies’. Orwell, then, was no ideologue.

For Orwell, socialism was first and foremost about ‘common decency’ (a phrase he used often). His views on the Soviet Union set him apart from the left-wing ‘establishment’ at the time. Unlike many other writers and public intellectuals in the 1930s, Orwell was neither beguiled by the Soviet Union (as a ‘pioneer’ socialist state) nor a (pragmatic) apologist for Stalin. He never believed that the ‘ends’ justified the ‘means’. His suspicions of the British Communist Party as mere ‘dupes’ of Moscow were confirmed in August 1939 when, after loudly demanding that Britain stand up to Hitler, the Party was, on instructions from Moscow, forced into an embarrassing volte face after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop (Nazi-Soviet) pact. The Party refused to support Britain’s declaration of war in September 1939 on the grounds it was an ‘imperialist’ war – a line it maintained until Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941.

Orwell’s outspoken criticisms of communist factionalism and abuses of power that he had witnessed in Spain had already alienated much of the British left (gathered as it was around the New Statesman magazine and Victor Gollancz’s Left Book Club). Orwell’s critics accused him of attempting to undermine the credibility of the Republican popular front. Later, in 1944, Orwell was surprised and angered when Gollancz (who had published Orwell’s work in the early 1930s and had gone on to commission The Road to Wigan Pier) declined the manuscript of Orwell’s satirical ‘fairy tale’ of the Russian Revolution, Animal Farm, because it was critical of Soviet-style communism. Other publishers also refused the manuscript on the grounds that the war against Germany was not yet won, and the Soviet Union remained a vital ally.

Orwell and Englishness

Orwell’s sense of ‘Englishness’ informed much of his writing. He had admired the ‘quiet’ patriotism he’d found within working class communities. In The Lion and the Unicorn (written in London in 1941 when Blitz was at its height), Orwell was adamant about the need for political change. However, he had more faith in the patriotic decency of the ‘common people’ than in the ‘Europeanised’ English intelligentsia who, Orwell claimed, ‘took their cookery from Paris and their opinions from Moscow’ (Orwell, 1941, p. 48). Owell set out an agenda for a very ‘English’ political revolution.

Writing in 1941 (when the end of the Second World War was still four years away), Orwell believed that the working classes would continue to make the necessary sacrifices just so long as they believed that they and their children could look forward to a better life when the war ended. The sort of socialist revolution that Orwell hoped to see (and which he believed would be necessary to build a just post-war society) would not be led by communists and it would not involve the hoisting of red flags or street fighting. Instead, it would require a fundamental shift of power – achieved through democratic means.

In 1941, Orwell did not believe that communism exerted any sort of popular appeal in Britain, but he was concerned that the appeal of fascism might be greater – as it had proved to be in civilised countries such as Germany and Italy. Orwell believed that a democratic socialist movement, which could win the support of the mass of working people, was the best guarantee against fascism taking hold in Britain.