1.1 The foundations of equity

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in our philosophy.

Following this famous quote from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, it can be argued that the plurality theory of equity turns on what can ever truly be known or understood about the nature of equity as such. Furthermore, it maintains that there are irreconcilable contradictions between different forms and ideas of equity. One of the most trenchant is between equity as a contemporary body of law and the far older and arguably more idealistic conceptions of equity that Aristotle outlined in the Nicomachean Ethics as ‘better than one kind of justice’ (Aristotle, 5.10).

Activity 1 Aristotle’s epieikeia

While Aristotle’s ideas of equity (or epieikeia) have evolved over time – having been constantly re-imagined and reinterpreted by philosophers, ecclesiastics, jurists, political theorists and economists to name but a few – they nevertheless remain a touchstone and help to remind us of equity’s enduring philosophical foundations.

Research how Aristotle defines and discusses equity, either online or in a local library. If you can find them, look for one of the following sections of his work:

- Section V ‘Litigation’ in Rhetoric (also known as The Art of Rhetoric)

- Book V in Nicomachean Ethics.

Don't worry if you aren't able to track these down – you can move straight on to the discussion below.

Discussion

While Aristotle defined equity in accordance with a very particular set of political conditions that applied during his lifetime, namely those that concerned city states in Ancient Greece (the polis), the enduring nature of his outline reveals that it touches upon fundamental truths concerning equity, law and legal reasoning. Even though equity as a ‘better form of justice’ appears to be a fairly abstract idea, it does not mean such ideas are without practical or real-world effects that we ought to take seriously. Equity, in that sense, has much in common with other powerful ideas or ideologies that describe particular indexes of human nature and conduct, such as the rule of law, democracy, capitalism or liberalism, for example. Each of these enfolds or contains a number of ideas or virtues that, should they be stripped away, would likely have profound social consequences. The same applies to equity, especially as it enfolds what are arguably two of the most important dimensions of social life: fairness and justice.

Aristotle addresses discrepancies between theoretical and practical forms of equity by suggesting that equity’s inherent purpose or nature is to fill gaps found elsewhere in the law. Gaps exist, Aristotle maintains, due to law’s innate generality or universality – that is, a universality that comes from the inability of the legislator, and other legal stakeholders such as judges and lawyers, to find solutions to each novel situation or problem that life presents. Equity exists therefore to serve a very singular purpose; one that draws on both theoretical and practical considerations in order to ensure that a better form of justice is achieved than that which the law alone can achieve. This ‘partnership’ with law is one of the main ways in which Aristotle situates equity in the general legal landscape (Majeske, 2014, p. 41). And via Maitland’s notion of equity as a ‘gloss’ or ‘supplement’ to the common law (1909, p. 18), it has proven a popular view among jurists.

However, despite the potency of the partnership or supplementary view of equity, it still assumes rather than satisfactorily explains any connection between equity and justice. After all, equity does not simply appear and disappear as justice requires; and equity is not justice as such. Therefore the two are not infinitely interchangeable, and equity cannot fully explain or describe what justice is and vice versa. Looking at how equity and law work together in order to produce forms of justice can arguably help to explain their relationship, at least to some extent.

If you would like to know more about Aristotle and his ideas, see the Very short introductions [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] collection. You might find it helpful to look at this resource when considering other thinkers and concepts in the course.

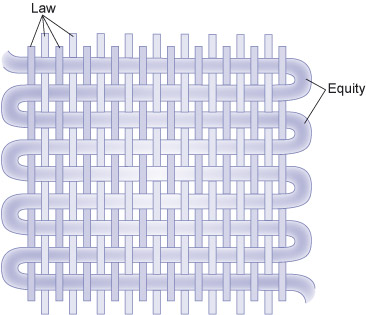

In Laws, Plato, like Aristotle, relies upon metaphors in order to explain how equity and law work together in order to achieve a better form of justice. In other words, Plato views equity in deliberately fictive terms in order that it may, as Terry Eagleton suggests more generally in relation to metaphor, ‘betray its own fictive and arbitrary nature at just those points where it is offering to be most intensively persuasive’ (1996, p. 126). And where Plato (who predated Aristotle) wants us to see equity at its most intensively persuasive is as a compliment to and corrective of the law. One of Plato’s more notable metaphors relates to fabric and weaving, and what is referred to specifically as the complementarity that exists in the interweaving between the ‘warp’ and the ‘woof’, where the warp, representing the law, ‘must be of a superior type of material (strong and firm in character)’, while the woof, representing equity, ‘is softer and suitably workable’ (Laws).

Both Aristotle’s and Plato’s accounts of equity remind us that there is nothing organic or natural about equity or the ways in which it contributes to and creates law. Rather, equity’s various meanings and how these translate into how it functions in the real world are conjured and controlled by the ‘reason’ of stakeholders who demand it exists in a particular way. A clear example of this relates to the fact that equity was and to some extent still is closely allied with many different religious doctrines and embodied in transcendent concepts such as the ‘Golden Rule’ (Wattles, 1997). Because of this the meaning of equity has often been shaped by religious bias and reshaped by secular backlash. This has seen equity, much like the concept of natural law, directly attributed during significant periods of its history to the will of God. The reality, of course, is that equity, like law generally, reflects or embodies a complex of human reasons, desires and needs, and this remains very much the case in the contemporary capitalist context.