5.1.1 The long peace

For Vannais (2001, p. 138), the 1994 ceasefires by both Republican and Loyalist paramilitary groupings not only represented a new beginning, which would eventually culminate in the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, they also marked a new phase in mural painting. She argues that most Nationalist/Republican mural paintings seemed to anticipate the ceasefire signed by Republican paramilitaries on 31 August 1994, while most Unionist/Loyalist paintings seemed to struggle to acknowledge the ceasefire had taken place long after it had been signed on the 13 October 1994.

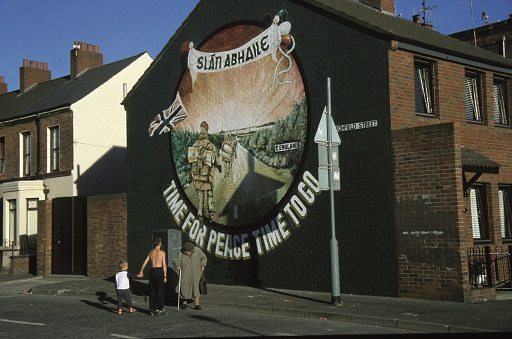

By 1994, British troops had been in Northern Ireland for twenty-five years. This anniversary was signalled by the appearance in Nationalist/Republican murals of a circular stencilled emblem which read ‘Time for Peace – Time to Go’ with the number 25 painted in the centre. Vannais (2001, p. 139) argues that this emblem, which became ubiquitous in Republican areas in the months leading up to the 1994 ceasefire, was a message directed not only at British troops but also at fellow Republicans. Vannais describes one Republican mural painted by Danny Devenny several months before the IRA ceasefire that appeared on gable walls throughout Belfast. The image is of a line of British soldiers marching down a road signposted to England. A banner above the soldiers, decorated with green, white and orange balloons, wishes the troops Slán Abhaile (‘safe home’ in Irish) and below this is the message: ‘Time for Peace, Time to Go’ (see Figure 9). Vannais (2001, p. 140) argues that what is remarkable about this image is how magnanimous the message is, given the levels of hostility against the British Army at that time.

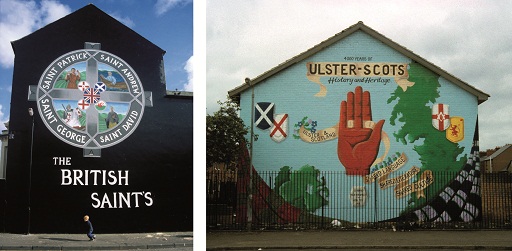

According to Vannais (2001, p. 142), the optimism and magnanimity that characterised the Republican/Nationalist murals in the period leading up to the 1994 ceasefire were not present in the Unionist/Loyalist paintings. As Nationalists and Republicans became increasingly assertive and confident in their public identity, Unionists and Loyalists were beset by uncertainty and a lack of confidence. Loyalist murals reflected this changing political landscape as the King Billy theme, which had predominated until the 1970s, began to be replaced by paramilitary themes (see Figure 10).

This uncertainty continued up until and after the 1994 ceasefires, when the message in loyalist murals became more militaristic and demonstrated none of the sense of impending change that could be found in the Nationalist/Republican paintings. It could be argued that this represents an example of zero-sum power, where gains by one side are perceived as losses by the other.

From the 1970s onwards, therefore, mural painting developed in each community in diametrically opposed ways. This trajectory continued through the ceasefires of 1994, into the political negotiations that followed and beyond the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which was the culmination of this process. Following the 1998 Agreement, Nationalist/Republican murals engaged with the process. Some were genuinely supportive of the new political structures put in place by the Good Friday Agreement, while others were critical of the way in which some aspects of the agreement were implemented (see Figure 11).

Loyalist paintings, on the other hand, were much more hesitant in engaging with the political process. This reflected the difficulties that the peace process posed for Unionists and Loyalists. Given that this community desired continued union with the UK, it is perhaps not surprising that the murals did not depict the same sense of change that the Nationalist/Republican murals did. On the contrary, they continued to depict Loyalist paramilitary gunmen, often with the slogan ‘No Surrender’. These militant murals served as a warning message both to Nationalists/Republicans and to their own politicians who were engaged in the negotiations. This is indicative of the ambivalence felt by many in the Unionist/Loyalist communities towards the peace process as well as the tensions between various paramilitary factions within the community.

These different developments in the murals of each community demonstrate the changing relationship of each to the state. They also express changes in the balance of power as murals are created or removed in attempts to demonstrate control over space and place. This case study of mural painting clearly reveals a distinctive and localised way in which disputes over ordering and legitimation claims manifest themselves and change over time, and the important role that symbols and images can play in such processes. As Republicans and Nationalists became more confident and secure in their relationship with the state, the murals began to demonstrate a more commemorative attitude, in much the same way that the early Unionist/Loyalist murals demonstrated their confidence through murals commemorating 12 July. Conversely, new murals by Loyalists and Unionists (see Figure 12) seek to move beyond paramilitary themes to depict new and broader cultural and historical themes, often borrowing icons used by Nationalist/Republican murals in much the same way that Nationalist/Republican murals sought legitimacy for their struggle when they began painting murals in the 1980s (Vannais, 2001, p. 156).

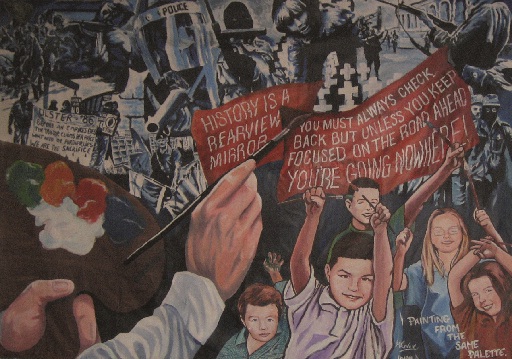

It is still too early to say how politics will develop in Northern Ireland as the power-sharing arrangements established by the Good Friday Agreement continue to evolve. Similarly, it is still too early to say what the fate of Northern Ireland’s murals will be, but there are indications that the tradition may evolve rather than disappear, not the least because they are an increasingly popular tourist attraction. In 2008, ten years after the implementation of the Good Friday Agreement and only one year after the historic power sharing in government that began in May 2007, a mural Painting from the Same Palette was unveiled at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the USA (Figure 13).

What was unusual about this mural was that it was painted by Danny Devenny, a former IRA prisoner and famous Republican muralist, and Mark Ervine, a famous Loyalist muralist. According to Danny Devenny: ‘During the war, the murals told the story of injustices we experienced. Now they show hope for the future’ (quoted in UMassAmherst College of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2008). Mark Ervine commented that while previous murals reflected the communities’ concerns about the conflict: ‘Now hopefully this is the beginning of ones that will reflect the peace’ (quoted in UMassAmherst College of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2008). The two artists have continued to work together, most recently on a series of murals depicting the Beatles to celebrate Liverpool’s term as Capital of Culture in 2008.

Summary

- There are two traditions of mural painting in Northern Ireland, which are indicative of two different relationships to the state.

- Mural painting is a visible way of claiming territory and affirming identity and a sense of belonging.

- Changes in mural paintings have denoted changes in each community’s relationship to the state as the peace process has progressed.

How do we know?

Looking for legitimacy

You have looked at a range of agents, institutions, practices and procedures through which states attempt to order aspects of our social lives. And you have seen that the idea of the state involves a constant work of claiming and receiving legitimacy. That is to say, you have been studying the state through its effects on our daily lives and through the routine, often taken-for-granted, ways in which it seeks to shape and regulate society.

You have also seen that the degree to which people acknowledge that state as legitimate is varied. In the examples of the citizenship ceremony and the ways in which different groups in Northern Ireland have sought to mark and claim public space, to represent their political identities in visual form, you have seen that the legitimacy of the state is contested, sometimes violently.

Here you have been ‘reading’ evidence about the legitimacy of the state through a study of its agents, institutions and practices as well as though the ways in which its subjects or citizens represent their vision of the state and their political identities. In particular, the murals of Northern Ireland can be seen as expressing ideas, views or orientations – and need to be ‘read’ as a source of evidence.