3 Settling islands

3.1 Voyages of discovery and settlement

In Section 2, we saw that there are momentous new and recently transformed flows that are impacting on island territories. Some flows have important precedents, and others may not be quite as novel as they first appear. In this section, we look more closely at some of the flows that have helped make, remake and sometimes unmake islands.

This takes us away from the flows that have captured recent attention, such as movement of goods or human-induced changes in climate, drawing us into the longer-term process of the formation of island territories. Beginning with the journeys that have taken human explorers and colonists to oceanic islands, we move on to other acts of settlement that are no less wondrous and impressive.

The people of Tuvalu, as we have seen from Readings A–D, are contemplating leaving their islands and shifting permanently to higher and drier ground elsewhere in the Pacific. Consequently, some islanders have already left for New Zealand. Migration, at least in this context, is a kind of flow which occurs as a response to a territory felt to be under threat or pressure. If some of the predictions presented by Conisbee and Simms (2003) in Reading 1B turn out to be accurate, the flow of migrants triggered by climate change and other forms of environmental degradation will dramatically increase over coming decades. Even without additional movements propelled by environmental causes, current rates of migration are already often referred to as ‘floods’ by people in receiving countries. Nevertheless, while there may be many new pathways and intensities of movement in the contemporary world, migration is far from being a novel form of flow.

Activity 5

While you have been reading the story of the threatened existence of the Tuvaluans, have you stopped to wonder how they came to be living on these islands in the first place?

How did the Tuvaluans come to be hundreds of kilometres from any other land, out in the wide open waters of the western Pacific?

Did the Tuvaluans’ ancestors once discover these islands? And, if so, where did they come from?

Europeans often talk about having ‘discovered’ many oceanic islands during an era of maritime exploration between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, when voyagers like Ferdinand Magellan and James Cook and their crews sailed through the Pacific. However, this is rather misleading for, as anthropologist Greg Dening (1992) reminds us, by this time the Pacific had already been thoroughly explored. As he tells the story:

There are more than 25,000 islands in the Pacific. Yet any one of them can be lost in an immense ocean that covers a third of the globe. Remarkably, in the central Pacific where a canoe or a ship could sail for months or for 5,000 miles and never make a landfall, every mountaintop that had pushed from the ocean bed, every coral reef that had grown above the ocean surface had been discovered before the European strangers had had the courage or the knowledge or the technology to discover the sea.

(Dening, 1992, p. 307)

Evidence suggests that the people who first populated the Pacific, whom anthropologists refer to as ‘Austronesians’, departed from eastern-most Asia and the islands off Southeast Asia. As geographer Patrick Nunn points out, leaving the mainland, or islands that are densely-packed and often visible one from another, and heading out into the open ocean where islands are hundreds or thousands of kilometres apart, would have presented an enormous challenge (Nunn, 2003). Moreover, as he reminds us, such voyages would have commenced in the context of a very different geographical imagination than the one many of us share today. As Nunn puts it: ‘It is difficult today to imagine ourselves without our knowledge of the world. We know the geography of the earth's surface, we have only to flick open an atlas to know instantly the bounds of the Pacific Basin, but the first islanders did not’ (Nunn, 2003, p. 222).

It is now believed that Austronesian peoples were the first in human history to master long-distance ocean sailing, and that they began to colonise the islands of the western Pacific some 3000–4000 years ago. Those who later continued to journey eastwards into the Pacific settled the islands of Polynesia. Known today as ‘Polynesians’, these people continued their way eastwards across the Pacific as far as South America and southwards as far as New Zealand (Aotearoa). Other Austronesians headed westwards across the Indian Ocean, eventually settling in Madagascar, off the coast of Africa (see Figure 7).

For a long time, Western anthropologists and historians toyed with the idea that most islands were discovered and settled accidentally, by sailors swept away from familiar waters. However, the fact that enough men and women arrived on newly discovered islands to create viable populations, and that there is evidence that they usually arrived with a whole range of plants and animals which they relied upon for food and other needs, suggests a much more organised pattern of settlement (Hau'ofa, 1993, p. 9).

Flying over the Pacific, I have looked out of the aeroplane window, trying to spot small islands. It seems like you can fly for hours without seeing even the tiniest speck of land, which makes you wonder how those early navigators ever found their islands or, having left, ever found them again. This is especially intriguing in the case of Tuvalu and other atolls which are, in the most part, no more than a few metres above sea level.

Those who have studied traditional Pacific navigation give accounts of seafarers gradually building up, over thousands of years, knowledge of swell patterns, wave refraction, currents, prevailing winds and the position of stars. Seafarers were also familiar with more ephemeral signs – phosphorescence, the colour or shape of clouds, the presence of certain fish or birds. By reading such signs, traditional navigators could precisely locate a speck of land in a vast ocean – a practice known in nautical terms as ‘dead reckoning’. Moreover, they could still sail home in this way in cases where their vessels were storm-blown hundreds of kilometres off course (Lewis, 1994).

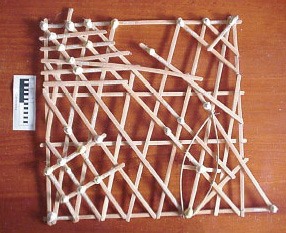

Marshall Islands stick ‘charts’, such as the one in Figure 8, are used for teaching about wave refraction around islands. Unlike most modern Western charts or maps that attempt to give a one-to-one correspondence with the area they represent, the stick chart is not intended to be in proportion to actual oceans and islands, and it does not necessarily refer to any specific area. Instead, it depicts the processes or dynamics by which swells hitting an island are refracted back into the ocean. It is for learning purposes only and is not taken to sea. It is said that traditional Marshallese seafarers could lie in the bottom of their canoes and navigate using the feel of waves and the current on the hull. This suggests that they relied less on visual recognition and cues than do most modern Western mariners.

Amid all the contemporary talk of accelerating long-distance migration, tourism and other flows of people around the world, it is easy to overlook how far and how frequently people travelled hundreds or even thousands of years ago. In the late eighteenth century, Captain Cook noted that Polynesian ocean-going canoes could sail far faster than his own ships, and he judged that they could ‘with ease sail 40 Leagues [120 miles] a day or more’ (cited in Lewis, 1994, p. 70). More recent evidence supports Cook's estimates, pointing not only to long-distance journeys around the Indian Ocean and across the Pacific, but also to very frequent trips between neighbouring island groups.

Pacific scholar Epeli Hau'ofa speaks of Pacific islanders, prior to European contact, engaging in a constant movement of ideas, goods and people which linked distinct island groups or territories. As he explains: ‘Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Niue, Rotuma, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Fatuna and Uvea formed a large exchange community in which wealth and people with their skills and arts circulated endlessly’ (Hau'ofa, 1993, p. 9). After much of the Pacific was colonised by Europeans, colonial administrators tried to restrict inter-island voyaging in an attempt to pin down and firm up the boundaries of various island territories. Hau'ofa tells of an earlier time: ‘the days when boundaries were not imaginary lines in the ocean, but rather points of entry that were constantly negotiated’ (Hau'ofa, 1993, p. 9).

Hau'ofa seems to be saying that islands, though they may be bounded in some respects, were certainly not closed or isolated. These were territories that were permeated by flows. Therefore, centuries and, in some cases, millennia before Europeans made their way across the world's oceans, Pacific navigators were already reworking sea and islands into a space in which human beings ‘flowed’. Although it is unlikely that they would have been able to imagine the world to be a single place – in the way it is now possible to think of the globe in its entirety – Austronesian and Polynesian voyagers succeeded in forging connections that spanned more than half of the planet's surface. In fact, with hindsight, it has been argued that these seafaring peoples made greater leaps towards globalising the world than any others, before or since (Gould, 1992, p. 109).

Looking at this long history of oceanic journeying helps to give a sense of the way human beings have been generating new flows – sometimes over very long distances – for thousands of years. These flows have been vital in establishing new territories by opening up lands for settlement. Nonetheless, it is important to see that the settling of new islands has not been achieved by humans alone. As was suggested above, Polynesian settlers travelled with a ‘portmanteau’ of useful animals and plants. Along with seedlings of the plants they needed for food and clothing, island colonists across much of the Pacific also introduced their traditional ‘feasting’ animals – pigs, dogs and chickens – to their new homes (Dening, 1992, pp. 307–8). In the case of Tuvalu, such staple foodstuffs as breadfruit, taro and banana would probably have been brought to the islands on board the canoes of inter-island voyagers.

It is worth considering more closely the dynamic relationship between territories and flows in the case of oceanic islands. We have seen in Section 2.3 how the concept of territory helps us to conceive of islands as a weave of many different strands. Like other territories, islands are inconceivable without the input and throughput of flows and, as with the notion of territory, one of the advantages of thinking through the concept of flow is that it can be inclusive of both human and non-human elements. Thus, when we consider the ways in which territory and flow are interrelated, it is possible to address the human and the non-human together, and to recognise that they often share similar dynamics.

Considering the interaction of territory and flow encourages a view of islands as having been made, rather than simply discovered or awaiting discovery. This making is ongoing: islands remain open to the possibility of being unmade or remade. However bounteous and balmy tropical islands may sometimes appear, we should not forget that making islands is difficult and often dangerous work. Every new arrival to an island – either human or non-human – has to find some way of weaving itself into the existing fabric of island life if it is to make itself at home. On smaller islands especially, newcomers may struggle to find enough of the things they need to sustain them, while the existing pattern of island life may be deeply disturbed by even a few impetuous new arrivals. In many cases, not only have new groups of human settlers caused much damage to the islands on which they have settled, but so too have the rats, pigs, cats and other predatory species that have accompanied such humans on their oceanic voyaging (Quammen, 1996).

Yet is it enough to think of human beings, working together with their companion species, as the producers of viable island territories? Human colonists did not settle barren rocks or bare coral in the middle of the ocean. They, and the useful species they brought with them, could never have settled themselves were the islands they found not already a rich weave of living and non-living things. If the story of how the earliest oceanic voyagers established new flows between distant lands is an awe-inspiring one, no less epic are the achievements of all the other life forms which had already made themselves at home on even the most isolated oceanic islands.