3.2 Work, worklessness and poverty

This section outlines the relationship between the Welsh economy and patterns of work and work experience in Wales. Regrettably, one of the more negative outcomes of the Welsh economy is the existence of high levels of poverty. In recent years this has been measured largely in relation to child poverty [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] :

‘The child poverty rate in Wales is 32 per cent, currently the highest in the UK where the average is 31 per cent. In comparison, Scotland and Northern Ireland have child poverty rates of 25 per cent’.

Subsequent research puts the figure at 29% and about constant over the past decade (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2013)

There are two ways in which the pattern of economic activity influences the level of poverty in Wales. The first of these is the way in which low wages depress family incomes. To be employed in Wales is no guarantee against poverty. In 2010, 23 per cent of men and 19 per cent of women in full-time work in Wales earned less than £7 per hour, leading to the conclusion that ‘Wales remains a low-pay economy’ (Kenway et al., 2007, p. 4). There are also spatial patterns associated with the distribution of low wages, with rural areas experiencing a higher incidence of low-wage occupations. The second influence the economy has on the extent of poverty is through the consequences of high levels of economic inactivity.

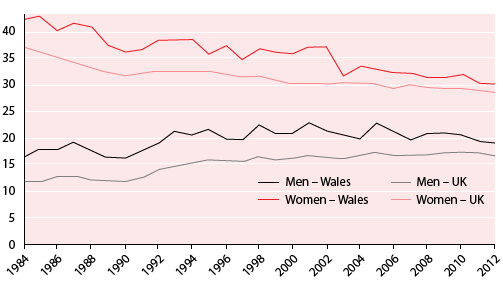

In this respect Wales reflects a wider experience of worklessness in areas previously dominated by mining, steel production and heavy industry. The period of collapse of the industrial base in Wales in the early 1980s was marked by rapidly rising levels of unemployment and economic inactivity. This latter term is more useful to employ as it includes many more categories of worklessness than simple unemployment. For example, it covers all those of working age who are not in work, including people with long-term sickness and disability and those who have retired prematurely as well as those who are currently seeking work. A clear pattern that emerged in the 1980s was the large number of people who were assigned to either Incapacity Benefit or Severe Disability Allowance. Figure 5 shows the rates of economic inactivity in Wales since 1984 and the contradictory gradual rise for men and fall for women. This is in part explained by increasing employment opportunities for women as employment in retail and services (traditionally employing more women than men) has increased in significance in Wales. However, the large numbers of Incapacity Benefit claimants in Wales is a major cause for concern and an increasing focus of government policy.

Activity 7

Examine Figure 5, which is drawn from a Welsh Government. statistical bulletin about economic activity. As you do so:

- Compare the rates of activity for men and women.

- Remember some of the processes you have read about in this section and note why the rate of economic inactivity continues to fall for women.

Discussion

This graph shows the simple numerical measurement of economic inactivity. You will have noticed that the rate of inactivity for men continues to rise, while for women there is a gradual fall in inactivity rates. This is a consequence of the feminisation of work. While it is important to understand statistically the levels of economic inactivity, it is also important to understand the social impact of high levels of long-term worklessness. In many communities in Wales three generations of economically inactive individuals can be found within single families.

Critically, worklessness and low wages can become concentrated in particular communities and families. The consequences for the individual, the family and community can be considerable. Additionally, in localities where low wages and economic inactivity are the dominant experience, a major cultural shift can occur which disconnects the community from the wider cultural values that underpin a commitment to work. Low levels of economic opportunity can create a fatalistic attitude which accepts a future of worklessness as the norm. Moreover, economic inactivity can become a rational choice in circumstances where low wages are coupled with precarious patterns of employment and a predominance of part-time and casual work. In such areas young people in the education system often lose motivation and a culture can emerge which rejects the academic values of the school and undermines educational performance. Peer pressures to conform to worklessness can develop and a general collapse of aspiration and confidence can dominate the local social experience.

These social and psychological adjustments to worklessness and low wages overlie the structural causes of underemployment in such localities. Intractable barriers to employment include geographical distance and isolation from places of work, poor transport links and, fundamentally, the low skills base of the population. To this can be added individual and communal values which reject travelling to places of work and which develop an acceptance of a lifestyle of poverty as normal and even satisfactory.

Just as the world of work has influenced Welsh culture in the past, the world of worklessness exerts a corrosive influence on engagement and participation in the wider community. Communities characterised by worklessness can become isolated and culturally marginalised, a process usually referred to as social exclusion. The social horizons of people living in such communities can become confined to the immediate area and the boundaries of the estate or community become the furthest social horizon for residents. Local cultural experience can become compressed and whole communities can lose their social and cultural links to the economy and the world of work.