5.1.2 Classlessness

This seems like a direct contradiction of the first image of class in Wales, but perhaps it is not as flatly opposed to it when we consider it more deeply. Seeing Wales as essentially working-class means starting our analysis with the ordinary people and stressing what they have in common. By contrast, in England people often refer to the class system as being a central feature. By this they generally mean that some people are born with major advantages and they hold onto them through going to the right school and mixing with people who have power and money – acquiring social and cultural capital. Class often, in this case, means snobbery and it starts our story at the top of society. When we say Wales is classless we mean that people have many values and attitudes in common, and come from similar kinds of small communities. We see Wales as ‘a community of communities’. In some ways it is another way of saying that we are all working-class.

Activity 12

Read the following passage.

What does it claim to be the nature of Welsh society, and what makes this different from English society?

It had often been remarked that class divisions between those living in Wales are less marked than in parts of England – in terms of the origin of income (most of the owners of land and capital are resident outside Wales), the distribution of income, and the differences of life-style. There is also a stress on locality – where one comes from – which masks status differences between wage workers and the few professional and managerial families in the ‘urban villages’. ... Even in towns as big as Swansea who you are (i.e. your place in the kin network) is often as important as what you are. In local affairs this leads to (what outsiders regard as) nepotism and a preference for locals.

Discussion

Part of what is being said here is that there are relatively few rich people in Wales; Wales is controlled by people who live in England, so Wales can be relatively classless and have a history of social conflict. The ‘enemy’ of the ‘classless’ Welsh is seen as living outside Wales. Nepotism (‘jobs for the boys’ – and it usually was boys) is based on kin and locality rather than institutions (‘the old school tie’).

But this argument of classlessness is most often used about the rural areas of Wales, rather than the industrial ones. An influential account of the Aberporth area after the Second World War argues that local people did not think in terms of upper, middle and lower classes but of ‘people of the chapel’ and ‘people of the pub’:

The distinctive characteristics of each group are its buchedd. ... The Welsh term buchedd (plural bucheddau) denotes behaviour, either actual or ideal, and thus corresponds broadly to the English term ‘way of life’. The same overall pattern of social life is found within each buchedd group. ... The two groups have a great deal in common ... The significance of the family and kindred is the same for both groups; ... Many members of both groups have the same occupations, the same working conditions, the same wages, leaving their houses at the same time in the morning and returning at the same time in the evening.

David Jenkins’s point is that local understanding of the society is based on moral criteria and lifestyle and has little or nothing to do with people’s occupation and income. Respectability is the key. However, this argument is not supported by the evidence of his own survey or of other studies of Welsh society (Day and Fitton, 1975). The respected people, the leaders of the chapel and the community in general, tended to be the better-off and more established residents. Indeed, one reason for the decline in religious observance in twentieth-century Wales was that the middle classes took such positions of power and prestige and were seen as forming an exclusive group.

The idea that the rural areas were classless probably arises from the fact that Nonconformity was once a mass religion and the basis of politics. The social distinctions within the countryside were overlain with a widespread adherence to the Liberal Party, and subsequently in many cases to Labour. The owners of large estates, from which farmers rented their land, stood outside this. They were identified as English in culture, Anglicans in religion and Conservatives in politics. There was an alliance of the other classes against them and for many people what they had in common seemed more important than what divided them. But there were still differences in income, farmers employed labourers, and there was a middle class of teachers and professional people.

There are other ways of assessing classlessness. One measure of class is income. There are very large differences in incomes between the best-off and the worst-off in Wales – it is far from classless. Differences of income on this scale mean that some people are able to afford very lavish lifestyles, often involving forms of conspicuous consumption (the display of wealth and standing through material goods). Their culture is bound to be different from that of people on the lower levels of income, who will often struggle to afford necessities and for whom all that is conspicuous about their consumption is the lack of it.

However, the scale of income inequality is a little less in Wales than it is in the rest of Britain. The poorest tenth of the population has, between it, around 1½% of Wales' total income; by contrast, the richest tenth have 25-30% of Wales’ income. The overall distribution of income has not changed much in the past decade, bar the recent sharp rise in the proportion of total income going to the richest tenth of the population (Department of Work and Pensions, 2011). The gap is very large, and we would surely notice the differences of income, culture and status if we saw the two groups side by side. As you will see, we don’t observe the differences as we don’t often see the two together.

Why is the share of income of the richest groups in Wales less than that of their equivalents in England? The answer is related to the class structure of Wales – that is, the numbers of people in the various social groups into which people are divided by census takers and sociologists. In Wales there tends to be a smaller proportion of the population in the better-off groups than is the case in England, and a higher proportion in the less well-off groups. This has been so for some time, at least going back to the 1960s.

Activity 13

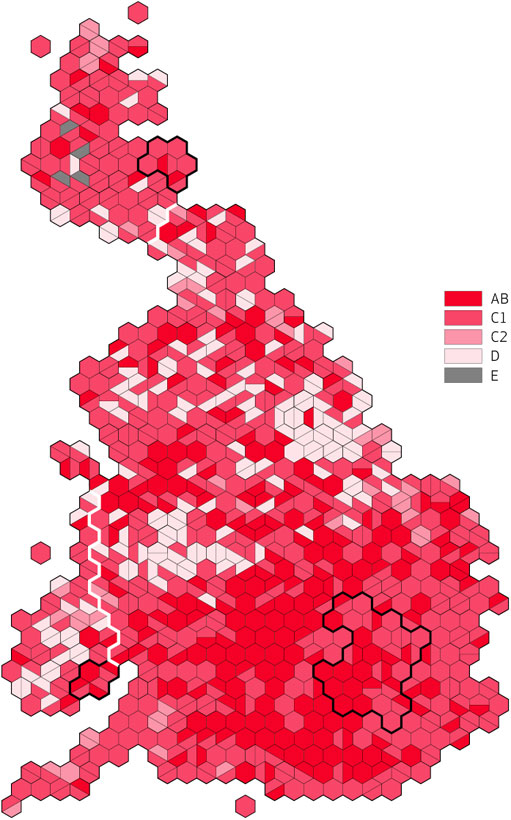

Figure 10 is a cartogram. A cartogram is a map on which statistical information is presented in diagrammatic form. Although this cartogram has roughly the same proportions of Great Britain as a map would, it’s really just a geometrical design to visualize the distribution of social classes in Britain: population differences distort the geographical shape, but you can still recognise the three distinct countries and their capitals. As each hexagon represents 100,000 people, no one area will be entirely one social class – but in each area one social class is in the majority. The numbers in the key refer to the social classes used in the census to categorise people. Earlier letters in the alphabet and lower numbers mean higher social classes.

- What does this tell us about the structure of classes in Wales in comparison with the rest of Britain?

Discussion

Figure 10 shows how small the concentrations of people in the higher social classes are in Wales – especially when we compare the situation in the south-east of England. There are also significant differences between areas of England. Some areas, like the north-east, are quite similar to parts of Wales. It might be misleading to compare England as a whole with Wales. We may need to think more about the divisions within England.

But there are very significant differences between social classes in Wales. So far we have concentrated on the average of Welsh society. What do we know about the small, well-off and powerful groups? The next two sections address these issues.