7.1.2 The Labour tradition in the 1980s and 1990s

The conditions which had helped mould the Labour tradition in Wales in the 1920s and 1930s almost disappeared in the last three decades of the twentieth century. The old Welsh industries which had helped sustain that tradition started to disappear. In the north, the slate industry fell into terminal decline in the late 1960s, devastating many local communities. In the south, coal mines and steel mills closed down with equally catastrophic social and economic consequences in the 1970s and 1980s. Unemployment in Wales reached 10 per cent in 1989 and peaked at 14 per cent in 1986. Of course, these are averages, with the picture much worse in many towns. Clearly, major political events in the 1980s – notably the 1984–1985 miners’ strike – had a devastating impact on ‘Labour’ communities but, ironically, these were not the constituencies that deserted Labour in the early 1980s.

Steel and mining areas, as we have seen, were symbols of Labour strength and values. The occupations which once supported the Labour Party in vast numbers all but vanished. Economic change was matched by challenges to old ideas and social structures and by the appearance of new injustices and inequalities, as well as new expectations. In many parts of Wales, the Labour tradition was threatened by competition from a cultural and political nationalism and from a popular brand of conservatism. At British level, the party was torn apart by bitter disagreements over policy.

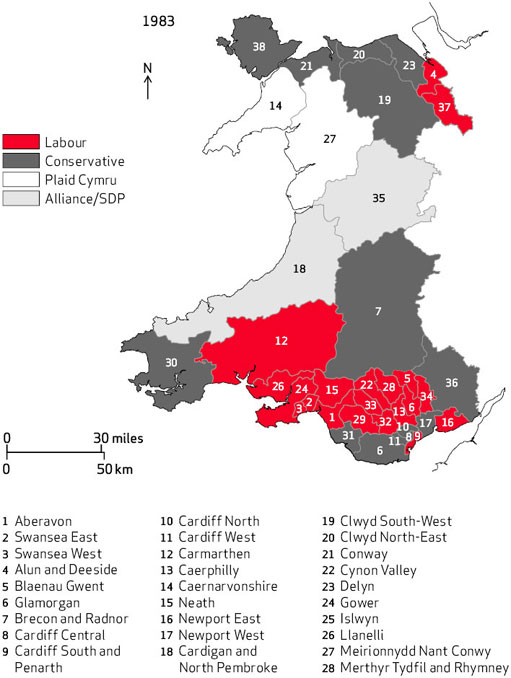

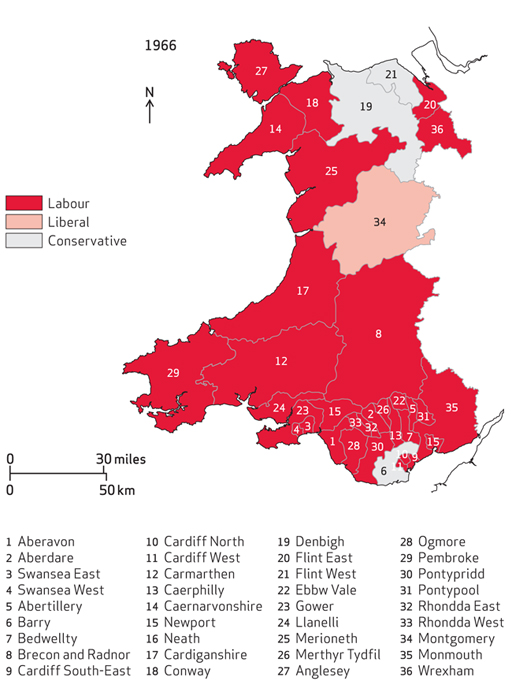

The crisis facing Labour in Wales was highlighted in the 1983 general election when the party’s Welsh vote fell to under 40 per cent for the first time in a generation. Figure 16 is a map of Wales following the 1983 general election.

Activity 21

Compare Figure 14 above with Figure 15, below, showing Wales after the 1966 general election. Consider the reasons for the erosion of Labour’s support.

Discussion

By 1987, Labour had lost three general elections in a row (1979, 1983 and 1987) and the social and economic problems facing Wales (outlined above) were forcing many pro and anti-devolutionists to think again. ‘Thatcherism’ had three negative consequences for Welsh democracy: (i) centralisation of power at Westminster; (ii) emasculation of local government by stripping powers away from many democratically elected (often Labour-controlled) councils; (iii) an increase in the number of (undemocratic) quasi-autonomous, non-governmental organisations (quangos).

Equally powerful in highlighting the crisis of a ‘democratic deficit’ in Wales was the Conservative Party’s performance in Wales during its years in power at Westminster (1979–1997). In the 1979 general election, the Conservative Party won 11 seats in Wales. In 1983, its best performance for more than a generation, it won 16. However, in 1987 and 1992, it won 8 and 6 seats respectively. In 1997, it failed to win a single seat, a ‘feat’ which the party also repeated in 2001.

So, the Conservatives ruled Wales on the back of English (and to a lesser extent) Scottish votes: the party did not enjoy majority support for Wales. This was one reason that some of those who opposed devolution in 1979 changed their minds in the 1990s. The realisation that the people of Wales consistently voted Labour, but were governed by the Conservative Party, started to sink in by the early 1990s. One convert to devolution was Ron Davies, Labour MP for Caerphilly and later secretary of state for Wales in the 1997 New Labour government. Read the extract below, which is from Davies’s evidence to the Richard Commission in 2002. This will help you understand why Davies saw the form the government that was operating before devolution as unsatisfactory.

Extract 8

I think that the point is worth making that the form of government we have now is infinitely better than we had before 1997 and in that sense I am proud of it. But that doesn’t mean it couldn’t be better. So the question is in what ways? I think we have improved governance in Wales ... there are a number of reasons why we had devolution, one of those clearly was the idea of the democratic deficit. There were others relating to the performance of public services and indeed the national question: identity and image and nation building. But the question that really resonated with the public during the 1990s was the question of the democratic deficit, the issue of the quangos, the issue of the Secretary of State, the issue of legislation going through Parliament. I think we have done that, I think that we do have a form of government now that, despite its imperfections, despite the sense of isolation that comes from its distant geography, I think we have opened up Wales.

It is important to stress that Davies was not alone in being won over to the positives of devolution.

A commitment to devolution had been included in Labour’s 1992 election manifesto. When New Labour under Tony Blair won a landslide election victory in May 1997, devolution was again a manifesto commitment. Later in the same year Welsh voters were given the opportunity to claim devolution. In the referendum of September 1997, 50.3 per cent voted in favour. The margin of victory was hardly a ringing endorsement of the executive form of devolution on offer, but it was a substantial increase in the ‘Yes’ vote compared to 1979. The 1997 referendum campaign took place in a very different political atmosphere to that of 1979. While there were still many anti-devolutionists in Labour’s ranks in Wales, few spoke out against the measure, not least because they did not want to undermine the status and reputation of the first Labour government for eighteen years and to risk the wrath of those who had suffered during this long period of Conservative rule.

The transformation in opinions over devolution were not due to a single reason, but to a variety of social, economic, cultural and political concerns. In the next section you will look at the development of the Labour tradition following the arrival of devolution.