7.2 Reorganizing notes

The technique of re-reading completed notes and supplementing them with comments and queries is a useful way of processing ideas. Another way of processing ideas is to reorganize notes around a set of questions or thematic headings. This is particularly useful for those notes that you will be drawing upon for planning and writing assignments. They can be reworked and key concepts and ideas can thus be applied to different types of questions and issues.

Activity 9(a)

Read the extract by Lucia Zedner taken from The Oxford Handbook of Criminology reproduced below. Use the skills that we have worked on in the earlier sections of this booklet to generate a summary of key ideas. Then organize those ideas by grouping them together around a number of themes or sub-headings. Afterwards, click the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article to read our feedback and comments.

Click below to open the extract by Lucia Zedner, Victims.

Victim [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

Discussion

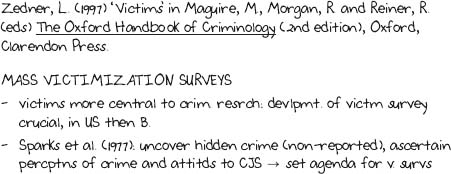

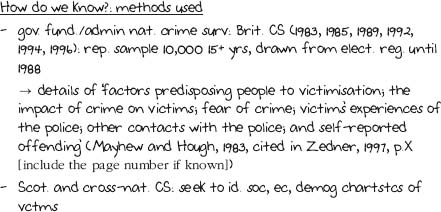

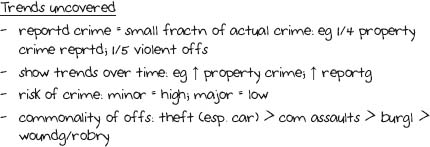

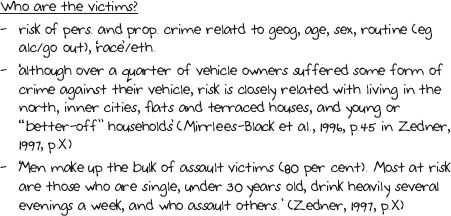

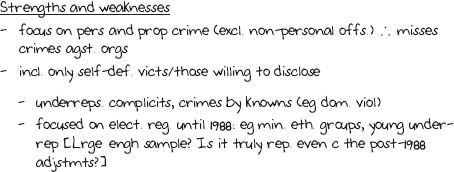

As with the last extract, we noted down the bibliographical details of the Zedner text at the top of the page. We then noted down a few questions that we not only tried to keep in mind when we were reading the extract but also used to help us organize our notes: What trends have victim surveys uncovered? Who are the victims? Are some groups of people more at risk of becoming victims of particular types of crime than others? How do we know? What methods are used in victim studies? What are the strengths and weaknesses of victim studies? Again, you might have started rather differently, choosing different headings or themes and focusing on different questions.

That's fine – the point here is to use a framework that is useful and makes sense to you.

Translation:

victims are now more central to criminological research: the development of the victim survey, first in the USA and then in Britain, has been crucial

Sparks and others (1977) uncovered hidden or non-reported crime and ascertained people's perceptions of crime and the Criminal Justice System, thus setting the agenda for various surveys

Translation:

the government funds and administers the national crime survey. British crime surveys have been carried out in 1983, 1985, 1989, 1992, 1994 and 1996, drawing on a representative sample of 10,000 people over the age of 15, drawn from the electoral register until 1988. The British Crime Survey gives details of ‘factors predisposing people to victimisation; the impact of crime on victims; fear of crime; victims’ experiences of the police; other contacts with the police; and self-reported offending’ (Mayhew and Hough, 1983, cited in Zedner, 1997 [include the page number if known])

there are also Scottish and cross-national crime surveys which seek to identify the social, economic and demographic characteristics of victims

Translation:

reported crime is only a small fraction of actual crime: for example, one-quarter of property crime is reported and only one-fifth of violent offences

show trends over time: for example, increases in property crime and the reporting of crime

risk of being affected by crime: high risk of minor crime; low risk of major crime

commonality of offences: the incidence of theft (especially car) is greater than common assaults, which is greater than burglary, which, in turn, is greater than wounding and robbery

Translation:

the risk of personal and property crime is related to geography, age, sex, routine (for example, alcohol consumption/going out), ‘race’/ethnicity

Translation:

focus on personal and property crime (excludes non-personal offences) and therefore misses crimes against organizations

includes only self-defined victims/those willing to disclose

under represents crime where the victim is complicit and crimes by those known to the victim (e.g. in cases of domestic violence)

focused on electoral register until 1988: e.g. minority ethnic groups, young people are under-represented [Is the sample large enough? Is it truly representative even with the post-1988 adjustments?]

Organizing notes around a number of questions (or themes) ensures that they are in a usable format from the outset. This saves time and also gets you processing the materials in an active way. Again, you should notice that we didn't always include detailed examples (we can go back to the highlighted bits of the text at a later date if required), though this time we did find one or two quotes which may usefully illustrate key points should we introduce them into an assignment, for example.

Activity 9(b)

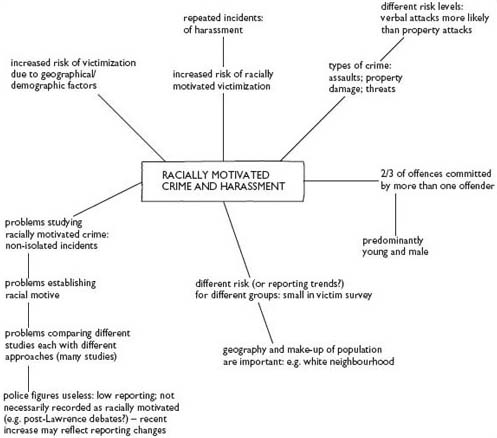

Try the note-taking exercise again but this time use the extract by David Smith reproduced below and try to organize your notes in a different way – that is, by constructing a spider diagram. This involves putting the main subject of the extract in the spider's body at the centre of the page and adding spider's legs around it, each with a different key point attached.

Spider diagrams are sometimes referred to as a concept or mind maps. You will find that the concept mapping software compendium has been included in the LabSpace area of this website. When you are confident of your spider diagram’s content, you could experiment with using Compendium to map out your thoughts. You might also like to share your compendium map with others by uploading it to LabSpace.

You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Reading 3

David Smith: ‘Racially motivated crime and harassment’

We have seen the elevated rate of victimization among ethnic minorities arises, to some extent, because these minorities fall into demographic groups that are at higher than average risk, and because they tend to live in areas where victimization risks are relatively high. However, another reason is that ethnic minorities are the objects of some racially motivated crimes. They may also be the victims of a pattern of repeated incidents motivated by racial hostility, where many of these events on their own do not constitute crimes, although some crimes may occur in the sequence, so that the cumulative effect is alarming and imposes severe constraints on a person's freedom and ability to live a full life. Racial harassment is the term that is used to describe a pattern of repeated incidents of this kind.

Genn (1988) and Bowling (1993) have pointed out that victim surveys have not been designed to describe patterns which develop overtime. Instead, they have aimed to count discrete incidents, using definitions parallel to those applied by the courts. This is most appropriate for crimes such as car theft or burglary, where most incidents are discrete from the viewpoint of the victim. It is least appropriate for crimes which take place within a continuing relationship (family violence, incest) or within a restricted social setting (the school, the workplace, the street).

A further difficulty in studying racially motivated crime or racial harassment is establishing racial motivation. One approach is to accept the victim's view; another is for an observer to make a judgement based on a description of the facts. Definitions used vary in the emphasis given to these two types of criterion, and in other detailed ways, so that it is often difficult to compare the results from different studies.

Although racial attacks and harassment, on any reasonable definition, are ancient phenomena, they have ‘arrived relatively late on the political policy agenda and thence onto the agenda of various statutory agencies’ (FitzGerald, 1989). The first major report on the subject, Blood on the Streets, was published by Bethnal Green and Stepney Trades Council in 1978. Since then there has been an official report by the Home Office (1981) based on statistics of incidents recorded by the police; a report by the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee (1986), which has also recently initiated a further inquiry; and two reports by an Inter-Departmental Group set up to consider racial attacks (Home Office, 1989c, 1991). National statistics on racial incidents recorded by the police have been regularly reported in Hansard. National survey-based statistics were first generated by the third PSI [Policy Studies Institute (police commissioned)] survey of racial minorities carried out in 1982 (Brown, 1984). More comprehensive information has become available recently from the British Crime Surveys of 1988 and 1992 (Mayhew, Elliott, and Dowds, 1989; FitzGerald and Hale, 1996) and from the fourth PSI survey of ethnic minorities carried out in 1994 (Virdee, 1997).

Police records are virtually useless as a measure of the amount of racially motivated crime, because most of these incidents are not reported to the police, and because incidents that the victim regards as racially motivated are often not recorded as such by the police (Virdee, 1997: 262). In an analysis of the PSI 1982 survey of ethnic minorities, Brown (1984: 260, table 134) identified assaults where there was a probable racial motive from studying victims’ detailed descriptions of the incidents. On the most restrictive definition (counting assaults only where the motive was plainly racist) the survey showed an incidence of racial attacks around ten times higher than revealed by the statistics derived from police records and published by the Home Office (1981). Police statistics have shown large rises in racially motivated crime since the mid-1980s, but, as Virdee (1997) has pointed out, this could reflect an increase in rates of reporting or recording, and does not reliably demonstrate an actual increase in the level of harassment.

In the BCS [British Crime Survey] (1988 and 1992 combined), 24 per cent of offences reported by South Asians and 14 per cent of those reported by Afro-Caribbeans were racially motivated in the respondent's view. Types of incident most often seen as racially motivated were assaults and threats, and also household vandalism in the case of South Asians. These surveys showed only a slight increase between 1987 and 1991, in marked contrast with the police statistics, which showed a large increase (FitzGerald and Hale, 1996: table 2.3a).

PSI's 1994 survey asked about three types of incident (attacks, damage to property, and insults) in the past twelve months where the victim thought there was a racist motivation. Looking at the results for ethnic minorities combined (Caribbeans, South Asians, and Chinese) it found that 1per cent had been racially attacked, 2 per cent had been victims of racially motivated damage to property, and 12 per cent had been racially insulted. These results suggest that over a quarter of a million people had been subject to some form of racial harassment over a twelve-month period, as compared with the 10,000 incidents recorded by the police. There were some fairly small differences in experience of racial insults between specific minority groups, but no significant differences in the case of racial attacks and damage to property. Men, and people aged 16–44, were more likely to be victims of racial harassment than women, and those aged 45 or more. Racial harassment was a considerably greater hazard for ethnic minorities living in a predominantly white neighbourhood than for those living in a neighbourhood with a substantial ethnic minority population. This suggests that black or Asian neighbourhoods have protective value for the ethnic minorities living in them (Virdee, 1997).

The PSI findings confirm other sources in showing that racial harassment tends to be a process involving a sequence of incidents, rather than an isolated event. In fact, three-fifths of those subject to racial harassment in the past twelve months had experienced more than one incident, and 22 per cent had experienced five or more. In two-thirds of cases, there was more than one offender. Offenders were predominantly male and young, but one-third of them were thought to be aged 30 or over (Virdee, 1997).

Local surveys, like the PSI survey, have generally tried to cover low-level harassment as well as criminal offences. They tend to suggest that racial harassment, on a broad definition, is a problem affecting a high proportion of South Asians and Afro-Caribbeans (London Borough of Newham, 1986; Saulsbury and Bowling, 1991). In a study of an East London housing estate, Sampson and Phillips (1992) found over a period of six months an average of four and a half attacks against each of thirty Bengali families, although seven families were not attacked, while six families were attacked twelve or more times. A sequence of incidents recorded for one family was: stones thrown and chased; threatened and prevented from entering flat; punched and verbal abuse; attempted robbery; chased by gang of youths; common assault.

Taken together, these findings suggest that there is a substantial risk of racial harassment for members of ethnic minority groups in England and Wales, although only about one in seven of Afro-Caribbean and South Asian people are conscious of having changed or restricted their pattern of life in response (Virdee, 1997: 285). Racially motivated crime also accounts for about one-fifth of crime victimization of ethnic minorities, and therefore helps to explain their elevated rate of victimization.

References

Bowling, B. (1993), ‘Racist Harassment and the Process of Victimization: Conceptual and Methodological Implications for the Local Crime Survey’, in J. Lowman and B.D. MacLean, eds., Racist Criminology: Crime and Policing in the 1990s. Vancouver: Collective Press.

Brown, C. (1984), Black and White Britain: The Third PSI Survey. London: Heinemann.

FitzGerald, M. (1989), ‘Legal Approaches to Racial Harassment in Council Housing: The Case for Reassessment’, New Community, 16, 1: 93–105.

— and Hale, C. (1996), Ethnic Minorities: Victimisation and Racial Harassment: Findings from the 1988 and 1992 British Crime Surveys. Home Office Research Study No. 154. London: Home Office.

Genn, H. (1988), ‘Multiple Victimization’, in M. Maguire and J. Porting, eds., Victims of Crime: A New Deal? Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Home Office (1981), Racial Attacks: Report of a Home Office Study. London: Home Office.

— (1989c), The Response to Racial Attacks and Harassment: Guidance for the Statutory Agencies: Report of the Inter-Departmental Racial Attacks Group. London: Home Office.

— (1991), The Response to Racial Attacks: Sustaining the Momentum: The Second Report of the Inter-Departmental Racial Attacks Group. London: Home Office.

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee (1986), Racial Attacks and Harassment. Session 1985–86, HC 409. London: HMSO.

London Borough of Newham (1987), Report of a Survey of Crime and Racial Harassment in Newham. London: London Borough of Newham.

Mayhew, P., Elliott, D., and Dowds, L (1989), The 1988 British Crime Survey. Home Office Research Study No. III. London: HMSO.

Sampson, A., and Phillips, C. (1992), Multiple Victimization: Racial Attacks on an East London Estate. Police Research Group, Crime Prevention Unit Series, Paper No. 36. London: HMSO.

Saulsbury, W., and Bowling, B. (1991), The Multi-Agency Approach in Practice: the North Plaistow Racial Harassment Project. Research and Planning Unit Paper No. 64. London: HMSO.

Virdee, S. (1997), ‘Racial Management’, in T. Modood et al., Ethnic Minorities in Britain: Diversity and Disadvantage. London: Policy Studies Institute.

Discussion

Our spider diagram is reproduced below. Once again we wrote the extract details on the top of the page. We also thought up some questions: What is the extent of racially motivated crime and harassment? Are all minority ethnic groups equally at risk? Do other social divisions, such as gender and age, have an impact?

Translation:

Some people find this alternative approach to note taking useful as diagrammatic representations can be more memorable – particularly useful then for revising themes and issues in preparation for exams. It is also easy to add on additional questions, ideas and examples at a later date. For example, you might want to make links to ideas presented elsewhere in your course materials, or something in the newspaper might provide you with a useful illustration. We felt that the debate around the Stephen Lawrence case and whether or not the police took racially motivated crimes seriously was relevant here, so we put a reminder to ourselves in brackets. Similarly, whilst the extract noted that different groups seemed to be more at risk than others of racially motivated crime, we thought the different percentages for South Asians and Afro-Caribbeans may be a reflection of different reporting patterns. So, again, we made an additional note to ourselves in brackets. It's a good idea, then, to get in the habit of revisiting your notes at intervals throughout your study to develop links, introduce new questions and examples, and thus continually reprocess key ideas.