2.3 Realist and conventionalist approaches

In most modern, urban, industrial societies, still images surround people for much of their daily lives: at home, at work, during leisure, while travelling. Does the evidence they offer differ fundamentally from that which comes from facts and figures printed on a page? It may be presented differently but we can derive socially relevant information as readily from a photograph as we can from written or numerical data. In some ways, it can be argued that the information that we can acquire from photographs may indeed be less abstract or arbitrary than that available from words and numbers.

This approach would argue that pictures are not the same as written facts and figures, which are quite clearly abstractions. If we compare the word ‘cow’ with a photograph of the same animal, it is clear that they differ markedly. The word has no direct relationship with the animal. It is, in effect, a sign in a code whose sound and appearance we take to signify or ‘mean’ the animal. However, ‘cow’ is ‘vache’ in French, so a different system of coding must be in operation when a different language is employed. However often we might insist on calling a ‘vache’ a ‘cow’ when in France, it will always remain a ‘vache’ for ‘les Français’. Although we may represent five cows by the number 5, it remains true that if we say or write that there are ‘five cows’ a French person will not recognise this as the same as ‘cinq vaches’.

Think again about a photograph of a cow. If we show it to the French person, they will recognise it immediately as ‘une vache’. An English person will recognise it immediately as a cow. A picture of five cows means the same thing in both languages. Now, does all this mean that a photograph is a different sort of mental thing from a word or figure? Or does it mean that pictures are like words and figures but that they operate in terms of a different language, one that may be more likely to be understood by people in many different cultures? (We should point out, however, that some anthropologists claim to have found non-western cultures where people appear not to recognise photographs as pictorial representations of real objects; see Barley, 1983.)

The idea that picture knowledge could be universal relates to what is known in philosophy as the ‘realist’ approach. Realism is the idea that a photograph of an object or a person bears a close relationship to that object or person. There is a link between the object or person photographed, and the photograph. The photograph, in other words, is a trace of something real. Because it was necessary for the object or person to be present at the moment of photographic recording, we can also say that there is a link between the photograph and the events, objects, people, etc., it depicts. However, photographers select images and have some control over how these are depicted.

Let us think of an example. A police speed-camera, for instance, records an event which we all (often rather ruefully) have to accept as realistic, truthful, or in other words evidential. However, notice that the apparent realism of photography also makes it open to fraud and deception. It is possible to manipulate an image so that its ‘photographic truth’ is subverted. During the Soviet era of Communist Russia (1917–1989), discredited leaders were regularly and most convincingly airbrushed out of the historical record, much in the same way that modern computer technology can merge images or change elements of the picture so that a wholly untruthful set of events is depicted. When Prince Edward married Sophie Rhys-Jones in 1999, the Royal Family decided that they did not like how Prince William appeared in one of the wedding photographs; so his head was digitally copied from one photograph and placed in the chosen image. Although the technology for doing this is very recent, the idea that photographs can be forged is very old. Digital photography has not invented image-manipulation or made deception any easier, it has merely changed the technology.

Running counter to the realist model, we can find another important strand of thought in the social and cultural sciences. This says that photographs are better considered as elements of a visual, symbolic language, which might have similar rules to a written and spoken one. We call this the conventionalist model, because it argues that images are best understood as assemblages of conventions about visual symbols that are socially constructed.

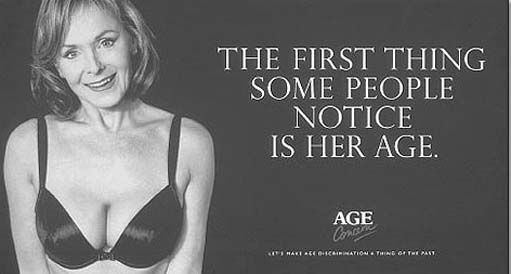

In this conventionalist view, pictures are assemblages of conventions, sets of symbols or visual devices that can be constructed so as to give a particular effect, to create a certain meaning. In order to understand the picture those looking at it have to understand the conventions. Think about the ‘Age Concern’ image seen previously at the beginning of this course. The point would be lost if we did not understand the conventions of advertising. The object of analysis is not, then, mostly what the photograph tells us about the situation of which it is a trace, but the values and norms that it presents.

It is clear that there are important social conventions that underpin what photographs look like. Whether rectangular, square or even circular, photographs mostly utilise a visual convention established in the European Renaissance, that of the easel picture. The edges of the picture delimit what can be seen. Our own ‘binocular’ vision operates in quite different ways, it rarely stays focused on one view for a long period and jumps around as we move our eyes, our heads and our bodies. Compositional devices – perspective, dark foregrounds and light backgrounds, strong diagonal forms, etc. – may focus our attention on one particular aspect of a picture. When we look at a photograph, we are looking at something that has been created using the visual language of pictures.

It would make sense to say that both realist and conventionalist approaches are helpful to us as social scientists. The first places emphasis on the information which the photograph can deliver about social practices and processes, the second offers insight into the social values and practices that underpin the making of pictures. In both cases, this may include information about the aesthetic as well as the political purposes of the photographer. All photographs (and all pieces of writing) have an aesthetic dimension since attention was paid to how effective they were as a means of communication when they were constructed. A realist approach does not imply that the artistic form of the image is ignored, similarly the conventionalist approach would not ignore the documentary information contained in a photograph.