5.2 From social construction to social constructionism

The notion of social construction, we have argued, is fundamental to a social science approach to the analysis of social problems. However, some authors have developed the notion further into a more focused perspective, which may be called social constructionism. This perspective starts by emphasising one essential feature of human societies – the role of language. In human societies, action is preceded by understanding and intention. We intend our actions to have meaningful outcomes. Our actions convey messages to other members of society. Although, as we shall see, some aspects of the social constructionist perspective can be quite complicated, it starts from a relatively simple point of departure. We might call this the naming or labelling of things. How we name things affects how we behave towards them. The name, or label, carries with it expectations.

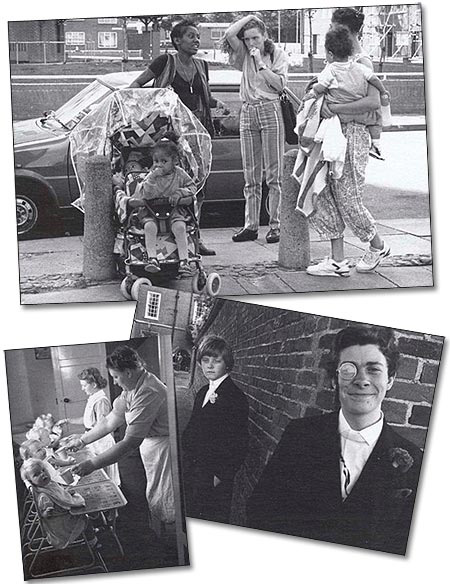

Let us consider the example of motherhood. The link between the biological facts of motherhood and its social expression are frequently taken for granted. The social constructionist approach has a rather different starting point. Thus we expect mothers (or, more accurately, ‘people who carry the label mother’) to love their children, be attentive to their well-being and to enable them to thrive. The label ‘mother’ carries a stock of social expectations, so that if a mother fails to behave in this fashion – if she abandons or abuses her children – we are likely to identify her as ‘unnatural’ and will anticipate finding something wrong with her that would explain her failure to live up to our expectations. What matters here, say social constructionists, is not the biology but social expectations. As with the label ‘mother’, many other names (the socially constructed identities or patterns of our society) are so well established, or ‘taken for granted’, that we view them as natural. From a social constructionist standpoint, the appearance of the word natural (or unnatural) is usually a warning that deeply embedded patterns of social expectations are at stake. The most deeply embedded aspects of our social arrangements have become so ‘taken for granted’ that we find it hard to think of them as social. Instead, we attribute them to causes or forces beyond society – to the realm of nature.

The point here is not to deny that there are important biological or natural differences between people, or even to deny the existence of certain shared biological drives – as ‘everybody knows’, for example, we all have to eat. Rather, it is positively to affirm the importance of the ways in which such differences are given meaning through processes of social construction. Thus, the person who gives birth to a child is called a mother (although, of course, it is also possible to become a mother through adoption). However, it is not clear that the same assumptions are made about the behaviour that follows from this biological relationship in all societies, at all times, or in all classes. In contrast to the model outlined above, for example, in some societies infanticide has been an acceptable form of birth control; in others child care has been shared through wide kinship networks; and in some social classes and at some times the passing on of babies to wet-nurses and then nannies, with little continuing maternal contact, has been viewed positively. Licensed forms of abandonment might also include the sending of children to boarding school at an early age. In all of these contexts it is the social expectations rather than the biological necessity that matters. In broader terms, what matters is the various ways in which a bundle of ‘natural material called the body is given a social meaning’.

Those who take a social constructionist approach (for example Burr, 1995) frequently contrast their position with what they characterise as essentialism. Essentialism is the belief that social behaviour is determined by some underlying process or ‘essence’ which works itself out in social contexts. In this context it should not be confused with the more common everyday use of the word, in which ‘essential’ is defined as something one cannot do without. Most obviously, perhaps, essentialism finds a reflection in the notion that each of us has some basic personality which then determines the way in which we relate to others and fit into the wider social system. Similarly, the notion of some shared human nature can be seen as essentialist. Any argument which explains social or human behaviour largely in terms of biological functions or evolutionary pressures (for instance in terms of ‘the survival of the fittest’) can be seen as essentialist. Critics of essentialism have not, however, restricted themselves to questioning biological determinism: they question any explanation which suggests that the best way of understanding social phenomena is to analyse them to find some underlying truth just waiting to be exposed. So, for example, classical Marxism has been criticised because it sees history as the working out of fundamental conflicts between classes which are rooted within a capitalist mode of production.

Activity 6

Can you think of any other features of contemporary social arrangements that are represented as ‘natural’ or non-social? Jot down any you can think of. List also any social arrangements in which people do not act in line with conventional expectations and which are identified as ‘unnatural’.

Discussion

We are not going to try to write out our own list here, but instead we are going to suggest that most of the things that we define as ‘natural’ are areas of life where particular sorts of physical or biological features of human life are visible. For example, our expectations about how people of different ages should behave are often seen as natural (particularly with regard to the young and old). As a consequence, we may think of older people who do not behave in a dignified and restrained manner (as befits their age) as behaving unnaturally. Similarly, issues about differences between men and women, or regarding sexuality, are usually assigned to the ‘natural’ realm. We could give further examples, but the main point here is the way in which ideas about the ‘natural’ order of things usually conceal issues relating to social arrangements and our conventional expectations about them.

Social constructionism – as a way of studying social arrangements – starts from the rather mundane point that the naming of things affects how we act, and develops into an approach which sees the whole edifice of society as socially constructed. One of the earliest attempts to develop this approach, by the sociologists Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann (1967), treated it as the means by which humans could create order out of the potential chaos of life. For them, social constructions simplified the business of living by establishing patterns of mutual expectations: mothers are like this, fathers are like this, children are like that, and so on. Such simplifying constructions were a form of energy-saving device. Rather than having to negotiate every aspect of life in each and every social encounter, social constructions – these simplifying typifications of people and behaviours – enabled people to proceed ‘as if’ we could all take these assumptions for granted. In time, such assumptions became habitualised – habits of mind that required little thought or attention. People forgot that they were constructions and they became naturalised – simply features of how the world is. In the process, people reproduced these constructions (and the assumptions behind them) in their behaviour. The social order is produced and reproduced through the ways in which we enact these social constructions. As individuals we find ourselves operating within a limited range of choice of positions – sometimes called subject positions – within that social order. For example, a mother may find herself exploring the options of housewife, working mother or single mother, each of which is constructed as a set of expectations about how she will act.

Berger and Luckmann's view of social construction is only one strand in the development of this perspective (see Burr, 1995, for a fuller introduction to social constructionism). In the following sections we will be looking at the possible links between the social constructionist approach and concepts of ‘ideology’ and ‘discourse’. However, what all of the different strands that have contributed to the perspective have in common is their stress on the way in which collective or shared understandings, interpretations or representations of the world shape our actions within it. Where they differ is in how they view these constructions. Some, particularly those associated with the concept of ideology, see constructions as a means through which social groups promote or legitimate their interests. Others, more closely associated with the idea of discourse, see social constructions as forming, rather than reflecting, social identities and interests.