2.2 A society frightened by crime?

We do not have to look too far to find someone saying that the UK is a society gripped by rising levels of crime, anti-social behaviour and incivility; or that disorder threatens social stability. The criminologist Robert Reiner suggests that ‘in the last 40 years, we have got used to thinking of crime, like the weather and pop music, as something that is always getting worse’ (Reiner, 1996, p. 3). So who is telling this story?

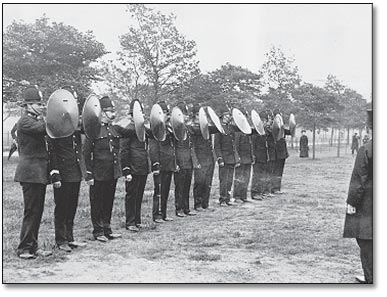

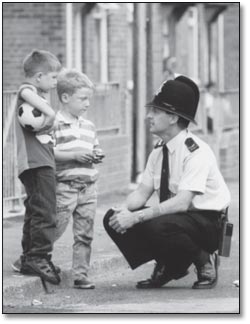

Most of us will have heard older family members and friends refer to ‘the old days’, even ‘the good old days’ when there was ‘more respect for authority’, when ‘people knew their place’, when ‘the elderly were respected by the young’, and when the vulnerable lived life unhindered by ‘thugs’ and ‘muggers’. A time when people were able to ‘leave their doors unlocked’ without fear of intrusion. A time when the local bobby was known and trusted, when the courts dispensed justice. A world of settled, stable communities and families, and strong and enduring community and family moral values.

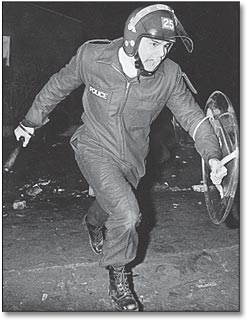

There appears to be no end of media reporting of crime. The story that gets told is of a transition between a secure, low-crime society to an uncertain society at risk from an epidemic of criminality and social unrest. A once solid homogenous society has become irrefutably fragmented and diverse. Newspaper headlines shout ‘communities under siege’. Articles splashed across their pages tell of drug-barons and teenage gangs that take over and terrorise communities. Cities are pock-marked by ‘no-go’ areas, made derelict by senseless acts of vandalism. Tales of sexual violence and child abuse have begun to appear with alarming regularity. The police are either incapable of controlling this disorder, or have even become part of the problem.

Seemingly crazed acts of violence by strangers make up the staple diet of the news reported on TV crime-solving programmes such as Crimewatch UK. Like most popular news broadcasts, the TV schedule is dominated by sensationalist or bizarre crimes. And it is not just tabloid papers and prime-time television that are telling these stories. Here is just one example reported in the late 1990s from the broadsheet press:

The terrified youth was chased from the wine bar by a gang. He managed only to get across the road before he was trapped on a railway bridge. He was kicked and punched before his tormentors lifted him over a wall and dropped him on to the electrified tracks below. Another everyday occurrence in Moss Side perhaps? No: this time it was Northwood, a well-to-do suburb on the borders of north-west London and Hertfordshire … The violence that was part of the lives of less well-off people in dangerous places … had finally arrived on the door steps of the middle classes.

(Independent on Sunday, 15 November 1998, ‘Urban nightmares disturb the slumber of Metroland’)

It is surely no coincidence that the rise of insecurity and uncertainty in areas previously perceived to be safe has seen politicians of all hues join in the story-telling. Crime has become one of the key policy concerns and rhetorical political devices of UK politics. Politicians persistently promise to turn the tide of rising crime; to re-introduce security and certainty into lives; to diminish risks; and to rebuild communities. Politicians, like everyone else, give these stories and these claims their own spin. Some argue that deprivation and unemployment are the problem; others look to the transformation and fragmentation of family life and the physical breakdown of old close-knit communities; and some see the problem in the permissiveness of the 1960s and the collapse of respect for authority of all kinds. Nearly everyone seems to talk of a general malaise of demoralisation and decline. An increase in crime can be linked to a breakdown in the bonds of community.

These narratives of crime represent what social scientists tend to refer to as common sense; the popular wisdom of the day, the taken-for-granted, ‘what everyone knows’ story. We are not saying that there is no grain of ‘truth’ in such arguments, that they are simply ‘wrong’, and social scientists will come along with the ‘right’ point of view. Many of the developments alluded to above are only too real. But there is always room for doubt.