5 Focus on ‘depression’ and ‘anxiety’

The word ‘depression’ has now entered the vernacular. Even lay people can be heard making a confident distinction between ‘clinical depression’ and everyday misery. What gives this taken-for-granted modern discourse extra significance about ‘depression’ is that it is the ‘common cold of psychopathology, at once familiar and mysterious’ (Seligman, 1975). Indeed, it is so common that we are told by the WHO that depression is a pandemic impacting on modern populations (Murray and Lopez, 1995). We can, however, ask, ‘a pandemic of what?’ There are a number of fundamental problems with this, the commonest of all psychiatric diagnoses (Dowrick, 2004; Pilgrim and Bentall, 1999):

- Depression is not easily distinguishable from normality (see above).

- Depression is not easily distinguishable from other diagnoses, especially anxiety states when life feels out of control, but also forms of psychosis when people are in a black tunnel contemplating suicide, and are desperate for ways out (Shorter and Tyrer, 2003).

- Experts emphasise different core features. Some claim that it is primarily a disturbance of mood (Becker, 1977) others of cognition (thought) (Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery, 1979). They also vary in the criteria required for diagnosis and some do not even define the condition but take it to be self-evident.

- Some cultures have no word for ‘depression’ (Wierzbicka, 1999). Western medicine often presumes that physical presentations in minority ethnic patients are masked depression: for example, some people from south Asia express distress mainly by pointing to their chest and describing ‘a falling heart’. Western psychiatry is arrogant to assume that this is a ‘somatic’ expression of what is ‘really’ depression (Fenton and Sadiq, 1991). This presumes that one cultural experience of distress is more valid than another.

Given the confusion and doubts about the term, when the diagnosis of depression is researched in randomised controlled trials of drugs or psychotherapies we can ask what exactly is being treated and assessed? Depression is a poor category and it is also poor because it is a category. This takes us back to the flawed logic of Kraepelin about natural categories. Depression is not a ‘thing’ but one way of conceptualising human distress which is now understood by many people to be a medical ‘fact’. However, what it signals is a persistent and universal tendency in human beings across time and place to experience profound unhappiness.

Moreover, the latter is not limited to human beings. For example, we can all spot a miserable dog (Pilgrim, Kinderman and Tai, 2008). Misery has been universally and trans-historically linked to loss: of people, control, status, dignity and so on (Brown, Harris and Hepworth, 1995). It reflects what Buddhists have always known of the clinging ego having problems in accepting change and the inevitability of suffering in the life span. Misery potentially, then, has a variable meaning for people but it is also easy to recognise the characteristic environmental conditions that increase the probability of any of us becoming depressed or anxious.

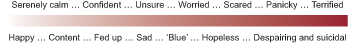

With regard to the anxiety aspects of misery, we find the same mix of global and historical continuities, as well as the lack of uniqueness of the human species (all mammals can be frightened, as we know). Moreover, fear brings with it certain predictable physiological consequences across time and place and across mammalian species (raised heart rate and blood pressure, sweating, muscle tension, etc). Thus depression or anxiety have some common behavioural and experiential features from person to person and even from species to species, but the meaning of their appearance in this person at this time in their life is what is at issue. If we want to find meaning in distress (rather than treat it as an unfortunate but meaningless affliction to be removed), then formulation, rather than a diagnosis, is required. Also, formulation assumes that there are not two categories of humanity (those ill and those not) but that our experience of emotions is on a fluid continuum. The way this might work is suggested in Figure 4.

Pause for reflection

What do you make of this continuum I offer using words from my own culture? Do you agree that misery can jumble feeling states above and below the permeable line or do you think they are always experienced distinctly? What might move people up or down the continuum? Write down your reflections on these questions in the light of your own experience of life.