2.1.1 Politics as that which concerns the state

Among the narrower definitions of politics is politics defined as that which concerns the state. As distinct from the government, the state comprises the permanent institutions that provide public services, enforce laws, ensure security and thereby provide for the governance of persons and the administration of things. The government, on the other hand, is composed of politicians who temporarily run the state because they have been elected (at least in democracies) to do so. The politicians determine the public services the state should provide, the laws it ought to enforce, the form of security it should ensure and the purposes for which the state should govern people and administer things. Politics defined as that which concerns the state can include: activities that either involve, or in some ways directly affect, the institutions of the state; individuals who are directly involved in the institutions of the state or the business of governance; and places in which these activities and people are present.

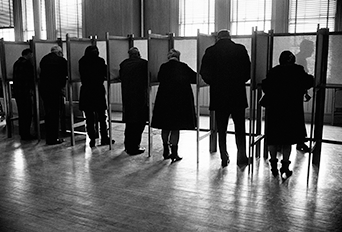

In light of this definition, the following could be included in the remit of politics: interactions between states in the international arena; the activities of politicians; and activities such as voting (in national, regional or local elections) through which individual citizens engage with the state. In even more concrete terms, politics that concerns the state might include:

- bilateral (or two-party) meetings between Canadian and Russian foreign ministers to resolve their territorial disputes in the Arctic

- multilateral meetings (between multiple groups) organised under the auspices of the United Nations to discuss issues such as climate change or nuclear non-proliferation

- the day-to-day activities of the European Commission in Brussels, which drafts proposals for new European laws

- debates and votes in the UK Parliament on government policy or proposed legislation

- or citizens voting in the general elections to choose their next government.

As you can see from this definition, politics, even in a narrow sense, is about much more than the activities (or careers) of politicians. Even when politics is confined to that which concerns the state, it involves a whole host of other activities, actors and spaces (from the more abstract or metaphorical space of the ‘international sphere’ to more concrete places such as the UN headquarters in New York or the Palace of Westminster in London).

Through a variety of state institutions, governments make and enforce laws that govern the conduct of those within their jurisdiction. They raise taxes through which they provide public services such as infrastructure, health care, education, employment and other social services. Of course, not all states provide citizens with the same kinds or quality of services. Likewise, successive governments may not always provide the same kinds of services as their predecessors. While one government may be concerned with the issue of national defence and channel more of its tax revenue towards the armed forces, another may reduce military spending and channel more revenue into infrastructure or health care. A further government may choose to raise levels of taxation in order to afford increased spending in both areas.

In addition to regulating and governing the conduct of those in their jurisdictions (persons, corporations or other entities) and providing public services, governments also interact with other governments in the international arena. In the most extreme situations, they may go to war with each other. More frequently, however, they interact with each other through international or regional organisations that attempt to regulate inter-state affairs, organisations such as the UN, the World Trade Organization or the African Union. Through participation in regional and international organisations, states attempt to cooperate on issues of regional or global scope such as international trade (by establishing tax-free trade zones or principles of fair trade), international crime (for example, drug trafficking or piracy) and global environmental issues (for example, climate change).

Given that all this can fall within the remit of politics, defined as that which concerns the state, you might think that this definition of politics is not actually particularly narrow. It does, after all, seem to include a lot of activities, actors and spaces. Indeed, many would agree with that assessment. But as you will later see, for many others this definition is still too narrow as it excludes or overlooks the myriad political activities that do not directly involve the state. Are anti-war or anti-globalisation protests political? Are boycott campaigns political, such as the global boycott of Nike in the 1990s or the more recent Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel? Are animal rights movements, or even the choice to not consume meat, political? For many of those who argue for a broader interpretation of politics, these can indeed be political. According to such arguments, this first definition, while incorporating a number of different activities, actors and places, is still too narrowly focused on the state.