This article was originally written to accompany The Mark Steel Lectures, a BBC/Open University co-production

Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960) was a socialist feminist. She played an important part in the women’s suffrage movement, in socialist and revolutionary politics and was a pioneering force in developing an understanding of imperialism, racism and fascism.

This article was originally written to accompany The Mark Steel Lectures, a BBC/Open University co-production

Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960) was a socialist feminist. She played an important part in the women’s suffrage movement, in socialist and revolutionary politics and was a pioneering force in developing an understanding of imperialism, racism and fascism.

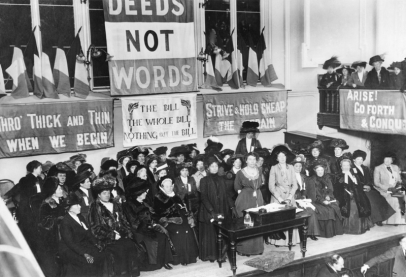

During the suffrage campaign she not only braved the horrors of hunger striking and forcible feeding, but also founded and built a remarkable women’s organisation in the East End of London - the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS). She attempted to forge a link between the women’s movement and the labour movement and in doing so was unafraid to tackle the vexed question of the relationship between class and gender, and between feminism and socialism. It was this question above all others which led to a major and irreversible split within one of the most important of the women's suffrage organisations, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU, commonly know as the Suffragettes, founded in 1903). This split mirrored the ideological rift with her mother, Emmeline, and elder sister, Christabel, the founders and prime movers of the WSPU.

The WSPU abandoned its early links with the labour movement in 1907 and, in 1914, with the outbreak of the First World War, it abandoned the suffrage campaign itself. Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst ardently supported the war effort and urged all women to do the same. Sylvia did not take their advice and was expelled by her mother and sister for her disobedience.

The East London Federation of Suffragettes, was composed of working class women who campaigned for the vote and for social change in the period 1912-1920. They maintained the suffrage battle during the war years as well as establishing many practical projects in the East End to relieve distress. The ELFS weekly paper, The Women’s Dreadnought (later, The Worker’s Dreadnought), owned and edited by Sylvia, had a high circulation and was influential outside London.

The ELFS moved steadily to the left during the war: it supported the Irish struggle for independence, the Russian Revolution and briefly played a role in the formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Sylvia Pankhurst was a pioneer in other ways. Apart from the fact that during her long and active life she founded and edited four newspapers, wrote and published 22 books and pamphlets not to mention literally countless articles, she was a founder and tireless activist in a variety of women’s, labour movement and international solidarity organisations. She was a deeply committed anti-racist and anti-fascist and involved for over 30 years in campaigning on such issues which included the cause of Ethiopia – the country which became her home for the last four years of her life and in which she was buried.

The independence of Ethiopia - “the black man’s last citadel” - was ended when it was invaded and conquered by Fascist Italy in 1935. Sylvia, almost alone among the white left, rallied to its cause and launched in 1936 the first edition of the New Times and Ethiopia News, a weekly paper which remained in circulation for 20 years and which, at its height sold 40,000 copies weekly. This included an extensive circulation throughout West Africa and the West Indies.

Emmeline and Christable Pankhurst

Influenced by the rising tide of rank and file militancy during the war years, and inspired by the Russian Revolution, Sylvia’s feminism underwent a profound change from 1917 onwards. Her organisation changed its name to the Workers’ Suffrage Federation (later the Workers’ Socialist Federation, WSF) and the Women’s Dreadnought was renamed the Workers’ Dreadnought. She was still committed to the women’s cause, but what had begun as a single issue campaign for women’s suffrage was transformed into a struggle to end exploitation not only for working class women, but for all workers.

Emmeline and Christable Pankhurst

Influenced by the rising tide of rank and file militancy during the war years, and inspired by the Russian Revolution, Sylvia’s feminism underwent a profound change from 1917 onwards. Her organisation changed its name to the Workers’ Suffrage Federation (later the Workers’ Socialist Federation, WSF) and the Women’s Dreadnought was renamed the Workers’ Dreadnought. She was still committed to the women’s cause, but what had begun as a single issue campaign for women’s suffrage was transformed into a struggle to end exploitation not only for working class women, but for all workers.

The relentless campaign for the votes for women forced the government to introduce a Franchise Bill in 1917. However its terms were unacceptable to the WSF and to all socialists since although, for the first time women were included in its provisions, it proposed to enfranchise only women over 30 on the basis of a small property qualification. Sylvia regarded this as a shabby all-party compromise which explicitly rejected the principle of equal suffrage.

The Bill gained Royal assent in February 1918. For Sylvia this was not a great victory for women and not a matter for rejoicing. In an article for the Worker's Dreadnought, she pointed out that "less than half the women will get the vote by the new Act...the new Act does not remove the sex disability; it does not establish equal suffrage." 17 women stood as candidates in 1918, the first General Election in which women could participate. One of the female candidates was Sylvia’s sister Christabel who stood for her newly formed and very short lived Women’s Party. (Despite its title this was not a feminist party. It was funded by the British Commonwealth Union, backed by the Coalition and by the conservative press.) Only four women were adopted as Labour candidates, none as Conservatives. The following year (1919) Lady Astor entered parliament as a Conservative - she was not elected, taking over her husband’s Commons seat when he entered the House of Lords.

Only one woman was elected in 1918: the revolutionary Sinn Fein candidate who had fought in the 1916 Easter Rising, Countess Constance Markiewicz. However, she refused to take her seat as a protest against British rule in Ireland.

By this time Sylvia’s increased disillusionment with the parliamentary process was evident. This was expressed in an important article she wrote entitled 'Parliament Doomed’. In it she advanced the view that Parliament’s decision to enfranchise women was made not, as was usually supposed, as a reward for war work. It was motivated by fear of Bolshevism. The women who enter parliament she argued, whatever their politics, "will go in and play the sad old party game that achieves so little" whereas those who remain outside, "the more active and independent women" remain "a discontented crowd of rebels". These rebels were waiting for the Soviets to replace parliament, which, according to Sylvia, had now become an outdated 19th century institution. She was mentioned as a possible parliamentary candidate for the Sheffield Hallam seat and, of course, refused on the grounds that she was "in accord with the policy of the WSF" which "regards Parliament as an out of date machine." Hostility to Parliament was later to become a major hallmark of her political position, isolating her from many other socialists during the discussions on the formation of the Communist Party.

In 1928 all women over 21 were enfranchised. To Sylvia’s embarrassment her mother, Emmeline, was selected as a Conservative candidate for Whitechapel and St Georges, the heartland of the old East London Federation of Suffragettes. Emmeline died in 1928, before she could contest the seat in the 1929 General Election.

Sylvia Pankhurst

Suffrage history has focused on the WSPU and to this extent Sylvia has been eclipsed by her mother and sister. Whereas Sylvia sought to build a mass movement among working class women, the WSPU after 1907 sought the support of wealthy, articulate or influential women in which the deeds of individuals were highly prized and received much attention at the time and by suffrage historians. This helps to explain why the British state has chosen to honour Emmeline and Christabel for their contribution to women's enfranchisement (with a statue to the former and a plaque to the latter outside Parliament) while completely ignoring Sylvia's role. The Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial Committee was formed in 1999 in an attempt to redress this historical injustice. The committee (the patron of which is Sylvia’s son, Richard Pankhurst) has launched a campaign in the labour movement to raise funds for a life-size statue of Sylvia as an emblematic symbol of the unsung heroism of thousands of working-class women who fought for the franchise and for socialism.

Sylvia Pankhurst

Suffrage history has focused on the WSPU and to this extent Sylvia has been eclipsed by her mother and sister. Whereas Sylvia sought to build a mass movement among working class women, the WSPU after 1907 sought the support of wealthy, articulate or influential women in which the deeds of individuals were highly prized and received much attention at the time and by suffrage historians. This helps to explain why the British state has chosen to honour Emmeline and Christabel for their contribution to women's enfranchisement (with a statue to the former and a plaque to the latter outside Parliament) while completely ignoring Sylvia's role. The Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial Committee was formed in 1999 in an attempt to redress this historical injustice. The committee (the patron of which is Sylvia’s son, Richard Pankhurst) has launched a campaign in the labour movement to raise funds for a life-size statue of Sylvia as an emblematic symbol of the unsung heroism of thousands of working-class women who fought for the franchise and for socialism.

It is perhaps less surprising that Sylvia Pankhurst’s role in the labour movement has not been fully recognised. Women have traditionally been marginalised in the socialist movement and by labour historians. Sylvia shared platforms with James Connolly and Jim Larkin, was active in publicising the growth of the shop stewards’ movement, was the first British socialist to welcome and publicise the Russian Revolution and among the first to draw attention to the dangers of Mussolini’s fascism. She certainly merits a place in the canons of the British socialism and ranks alongside such contemporaries as George Lansbury and Keir Hardie. What emerges clearly is that Pankhurst was not a "bit player" - she was an initiator and a leader in her own right and made a substantial contribution as one of the first propagandists for Bolshevism in Britain. Her group, the Workers' Socialist Federation, (WSF) was the first in Britain to affiliate to the Third International (Comintern). Indeed in his writings on Britain, Lenin makes no less than 10 major references to Sylvia Pankhurst – more than any other British revolutionary socialist.

Although her work on Ethiopia, informed as it was by anti-racism and anti-imperialism, passed largely unnoticed in Britain, it was widely appreciated by black people in Africa and in the black diaspora. W. E. B. Dubois, arguably one of the most important black leaders of his day, expressed the view of black radicals in the following tribute he paid to Sylvia. “I realised... that the great work of Sylvia Pankhurst was to introduce black Ethiopia to white England, ...and to make the British people realise that black folks had more and more to be recognised as human beings with the rights of women and men.”

Clarification: In the original version of this text, the text implied that Emmeline had been unsuccesful in her attempts to win the Whitechapel seat in 1929. As commenter Elaine Ellen pointed out, as she had died in the year before the poll took place, it's not correct to say that she stood for parliament at all. We've reworded the paragraph to make clear that she was selected as a Conservative candidate for the seat, but died before the election was called.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews