Community Owned Solutions

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | 1 Core Concepts |

| Book: | Community Owned Solutions |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 23 November 2025, 5:09 AM |

1. Introducing Community Viability

Viability means to survive, to be healthy and to prosper. However, for a community this is not easy. Sometimes the situation is stable, sometimes conditions vary from the normal, and sometimes things change forever. A community therefore has to continually react and adapt to its environment. This environment might be the physical situation such as the weather, plants or animals. However, the environment also includes economic, cultural, political, legal, and social factors. Communities need to develop strategies to cope with all these different aspects of the wider environment and they need to be careful to ensure that all their survival strategies are at hand to deal with an increasing number of different challenges.

The community viability map shown in the next video was created using information collected from Indigenous communities across the Guiana Shield of South America. These communities live in remote forest, wetland and savanna areas, often rely on subsistence farming in the forests, hunting and fishing for food and have different cultural and language heritages.

For each category of community viability in the list below, Indigenous communities identified different survival strategies that were important to them. Some of these may be relevant to more than one category, but the aim of the diagram is to show that there are many different survival strategies a community possesses. It also helps to show the tensions within communities. For example, if you just collect resources for basic existence, it means that there are less resources for sharing with other communities. If too many of your strategies are resisting change and maintaining your identity, this can take away resources for adapting to new changes. A viable or healthy community is one in which there is a balance of strategies between the different community viability categories.

The video also shows a community viability map example of different survival strategies that could be employed by a community group living alongside urban wetlands in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Categories of viability

1. How do we meet our basic needs? – to exist under normal environmental conditions, you need basic resources such as food, water, heath, shelter and fuel.

2 - How do we maintain our identity? – to resist temporary changes in the environment, you need to draw on traditions.

3 - What gives us choice and flexibility? – to be flexible in a highly variable environment, you need to have more options.

4 - What helps us to be organised and efficient? – to be successful when resources in the environment are scarce, you need to become efficient.

5 - How have we adapted to new challenges and influences? – to adapt to major and permanent changes in the environment, you need to learn to do new things.

6 - How do we work with others? – to co-exist with other communities and/or organisations and institutions outside the community, you need good relationships.

2. Introducing Community Owned Solutions

Community owned solutions is an approach that promotes the abilities that are already found within a community. This type of approach is termed a strengths-based approach. It focuses on and explores the capacity, skills, knowledge, connections and potential of individuals within a community and of the community itself.

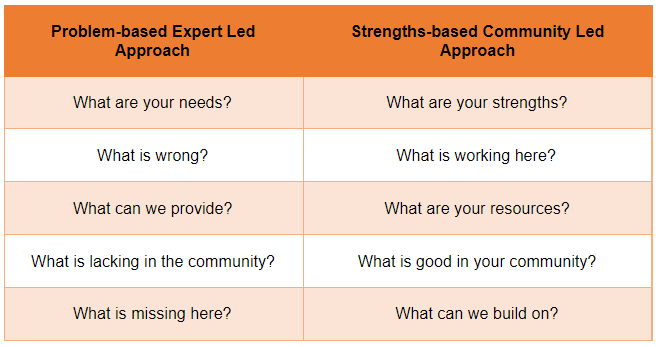

This concept comes from observations that challenges within a community can be better solved by identifying positive practices from within that community and trying to promote their use, as opposed to focusing on behaviours that are negative and trying to fix them with solutions that have emerged from outside of the community (Table 1).

Community owned solutions are practices developed and carried out by communities themselves. The solutions contribute to the well-being of communities in the present and in the future. They are born, developed and implemented in the communities, by the communities, for the communities, with little influence from external stakeholders. They are fair to all members of the community and they do not negatively impact on the environment as shown in the list below.

What is a "Community Owned Solution"

- The community needs it

- The community does it

- The community controls it

- The community benefits from it

- The solution is fair

- The solution is good for the environment

- The solution is self reliant and not dependent on long term external support

Although many community owned solutions are developed from within the community, ideas can also emerge from the outside. If these are adopted and adapted by the community, then they can become community owned solutions. However, these innovations need to fit into, and support, the strengths of the community, rather than undermine community solutions.

As the image above suggests, importing food into a community for its food security might help and offer a temporary solution but also creates dependency and disempowerment. Promoting local solutions to food security (like local techniques and knowledge for food production) is empowering and promotes independence.

Why record and share community owned solutions?

You could easily identify community owned solutions without needing either to record them or showcase them to external audiences. However visual recording and sharing provides the following benefits:

- If a solution works well within one community, it could be used as inspiration for another community who might be facing a similar challenge.

- ‘Communities that share directly with other communities’ challenges the expert-led process, where ‘experts impose their ideas on communities’. Communities that share have a greater chance of understanding each other’s problems and finding the best solutions. Solutions are less theoretical, more realistic and engaging, showing how things actually happen in real life.

- It can encourage people who were initially hesitant or reluctant to participate to contribute, as they immediately see outputs which they can identify with.

2.1. Parable of the Chilean Potato

An example of what we mean by 'community owned solutions' is the now infamous 'Parable of the Chilean Potato' promoted by Paul Hawken, a leading environmentalist and social activist. This is how Arie de Geus recounts the parable:

'Parable of the Chilean Potato'

There was a time when the Chilean economy was in trouble because much more was being imported than exported so the economy was crashing. The cause seemed clear: Chile could no longer produce its own food and had to rely increasingly on imports. The US decided to offer a helping hand and dispatched a team of agriculture experts to study the problem.

The team flew to Santiago and then onto to the Andes Mountains. The Andes is where the potato originated; it is still the main food eaten in Chile. Potatoes have grown for thousands of years at considerable heights in the mountains.

The US experts visited the potato fields. The fields were on steep mountainsides. They had highly irregular shapes and were very stony. Within each field, the experts discovered 10 or more varieties of potatoes growing. There were round potatoes and long potatoes, red, white and blue potatoes; and concerning to the experts – some plants which produced many potatoes and others which produced very few. This seemed terribly inefficient.

At harvest time the experts noticed that the villagers were not following a system of digging and appeared to them as almost 'lazy' in the way they collected the potatoes. Many plants in the corners of the oddly shaped fields were overlooked and left to grow wild. By then the experts had reached their conclusions. Their calculations showed, beyond doubt, that the more careful selection of seed potatoes, a switch to higher yielding varieties and more systematic weeding and cropping of the fields would increase the annual crop by at least 15%. Conveniently this equaled the shortfall in the country's food production, the team took their plane back to the US with the feeling of a job well done.

But the advice was wrong. However scientific the experts' approach may have been, they could not compete with the accumulated local experience, based on thousands of years of potato growing in the Andes.

Chilean villagers, based all their lives in the mountains, knew that a wide variety of terrible things could harm their potatoes. There may be a late night frost in spring or a caterpillar plague in summer. Mildew might destroy the plants before any potatoes have formed or winter might come too early. Over the years, each of these problems has taken place from time to time.

Whenever a new problem happens, the villagers walk up to their fields and look everywhere – in the corners, beyond the rocks and amid the weeds – for the surviving potato plants. Only the surviving plants are immune to the latest plague. At harvest time the villagers will carefully dig up the survivors and take the precious potatoes back to their homes. They and their children may have to go through a winter famine, but at least they have next year's potatoes from which a new start can be made. They are not locked into a particular set of farming practices or a particular type of potatoes; they may be inefficient at times, but they have diversity spread into their everyday practice, diversity which allows them to meet future challenges.

Arie de Geus (1997) Adapted from The Living Company, pp. 177-179