A process for visual storytelling

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Grassroots Visual Storytelling |

| Book: | A process for visual storytelling |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 2:25 AM |

Table of contents

- 1. Where to start? - Picking your seed

- 2. How to question your stories? - The Iceberg metaphor

- 3. Rich pictures - Planting your seed

- 4. Photostories - Watering your young seedling

- 5. Video Narrative - Harvesting the first crop

- 6. Journalistic video approach - Sharing your harvest with others

- 7. Participatory Video - Growing your seeds together with others

1. Where to start? - Picking your seed

The starting point for telling your story is you. No matter if you already have a clear idea of what you would like your story to be about or if this whole idea still seems quite daunting to you - there are great stories within each of us as well as the capacity to bring them out. For this project, we want to tell captivating stories about community food growing initiatives that explore the many ways they can contribute to building a radically hopeful future.

Storytelling always has two roles: the storyteller and the listener. You are going to be the storyteller here. So, the next step is determining who your listeners are going to be. Knowing who you want to tell your story to can help you define exactly what you want to say and think about what type of language and framing you might want to use. Your listeners could for example be your other community members, other community garden initiatives, potential community members that you might want to attract or decision-makers in your local context. For each of those groups, you can tell your story in slightly different ways that will best suit their approach using language that is familiar to them and that they can relate to. In professional terms, this is called your audience and can help you set the tone of your story. Thinking about your listeners and audience is really related to the purpose and potential impact of your story. We will talk more about the impact and dissemination of your stories in the final part of the course.

Activity (10 minutes): Exploring community flourishing

Go back to the padlet exploration of community flourishing and resilience. Spend a few minutes re-exploring the page and note down any thoughts, ideas or feelings in your learning journal. What kind of images come up for you? Do these images and writings remind you of something in your own community garden?

Is there one thought, image, feeling or story that stands out to you in particular? Hold onto that thought, this will be your seed.

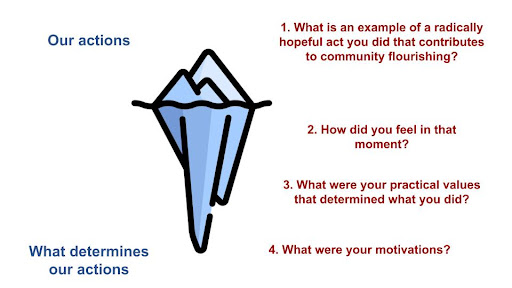

2. How to question your stories? - The Iceberg metaphor

Whether it is through writing or oral, storytelling is a performative act. There might be a discrepancy between the reality and your story. It is not a direct representation of what happened. In fact, it can never fully encapsulate an event objectively. But how we tell that story and use words, narratives and characters might subtly or explicitly reveal some of our underlying structures, beliefs, values and patterns. What we call the underwater iceberg!

A crucial aspect in storytelling is an appreciation of the 'iceberg'. The iceberg is a great metaphor for allowing you to engage with what is out there. A lot of us see things happen, we look at the news, for example, and we treat individual news items just as events. Even in our day to day we often feel like we are just firefighting; we’re just reacting to the events that hit us and we’re just rushing from one challenge to another. But, metaphorically, that is just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ that is above the surface of the water. It’s what hits us in our daily lives. The ‘Iceberg model’ demonstrates that storytelling can go beyond a simple description of events that have taken place, and/or are in the process of unfolding. It's about understanding that below the surface of what is more immediately apparent, there are patterns and structures connecting different events which result in certain outcomes. But more significantly, it’s about understanding the values which underpin behaviour. How we tell our story, the linguistic tropes, the arc we use, and characters, should engage with the underlying patterns, structures, beliefs, and values that we are challenging and/or championing. Once we are reflecting on these underlying glacial structures, we can actively use this self-awareness in our stories and lives and might even be able to change and alter some of these processes, questioning our assumptions and values. Ultimately, engaging with our own and trying to understand other’s icebergs is a way of transforming the way we act and see the world.

Let's look more concretely why an Iceberg approach might be fundamental to one of today's contemporary crises, climate change. This crisis is often approached through an objective scientific lens. To fix the climate, we must be rational and objective. We need to create new innovative structures, implement those net zero policies, and propose new conservation schemes. But, how can these actually change our behaviour? What are the mechanics underlying our behaviour? As we have seen with the iceberg metaphor, to change people we must change the hidden part of the ice. We need to question the values, assumptions and processes that underlie our behaviour. Instead of looking at climate change through a rational lense, we must complement it with an emotional perspective that encourages people to re-evaluate their value systems, like, for example, how participating in community food growing in one’s spare time is more fulfilling and generates greater well being compared to other high-carbon emitting pastimes.

Activity (20 minutes): Mapping onto the Iceberg Metaphor

Take a few minutes now to explore your community food growing initiative in terms of the iceberg metaphor:

1. What is an example of a radically hopeful act you did that contributes to community flourishing?

2. How did you feel in that moment?

3. What were your practical values that determined what you did?

4. What were your motivations?

3. Rich pictures - Planting your seed

In this step, we’re going to plant the seed of your story. For this, we first have to fertilise and prepare the soil and then to carefully plant your seed, which we will do by creating a rich picture.

When looking for inspiration for a visual narrative, often a good way to start is by drawing a Rich Picture. A rich picture is a visual brainstorm where you can explore a topic freely, exploring ideas, emotions or thoughts about a certain topic. Rich pictures are a compilation of drawings, pictures, symbols and sometimes text that represent a particular situation or issue from the viewpoint of the person or people who drew them. They can show relationships, connections, influences, cause and effect. They can also show more subjective elements such as character and characteristics as well as points of view, prejudices, spirit and human nature. The idea of using drawings or pictures to think about issues is common to several problem solving or creative thinking methods (including therapy) because our intuitive consciousness communicates more easily in impressions and symbols than in words. Rich pictures can be regarded as pictorial ‘summaries’ of the physical and emotional aspects of the situation at a given time. They are often used to depict complicated situations or issues.

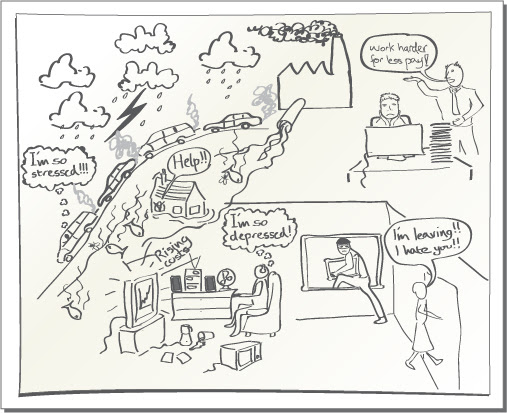

As examples, we developed the rich pictures below to quickly, and visually, brainstorm some of the worries and aspirations of a household that lived next door to one of the authors as they were exploring how they could improve their wellbeing and that of their community. The first rich picture shows some of the concerns the couple had at that moment in time: stressful commuting to work, stuck in traffic; worries about climate change and increasing weather disruptions; decreasing wage package and pension benefits; rising fuel and food prices; decreasing security in the streets and community spirit; increasing consumption of consumer goods; increasing levels of waste and air pollution; leisure time spent alone watching television. All these pressures combined to create a lot of tension and stress within the couple.

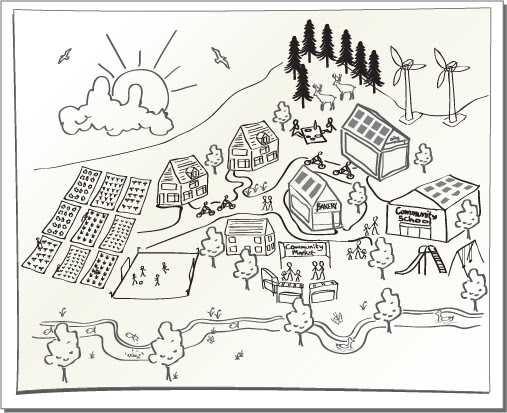

The second rich picture shows how we used the rich picture technique to explore what is, and what could, work well in their lives: working locally; contributing towards maintaining a stable and predictable climate (rather than contribute to emissions which will lead to more extreme weather events); higher quality of life reliant on local resources (e.g. growing food locally and generating electricity through solar panels) not dependent on an ever-increasing salary in order to pay rising bills and living costs; fresh air, clean water and open green spaces; more time for spending with family and friends in fun, relaxing, productive, useful activities.

A rich picture offers a great deal of scope for creative thinking and freedom in how you represent your ideas. A lack of drawing skill is no drawback as symbols, icons, photographs and/or text can be used to represent different elements.

Drawing a rich picture is often done most effectively as a communal activity, so that the different stakeholders in a situation can portray things as they see them. They are made up from:

- pictorial symbols

- key words

- cartoons

- sketches and symbols

- a title

It is usually best to avoid too much writing, whether as commentary or as ‘word bubbles’ coming from people’s mouths, although some people find it easier to use short phrases than to try to come up with a pictorial representation of ideas difficult to represent visually.

If you’re interested in a more detailed guide for how to draw a rich picture, you can also watch this video:

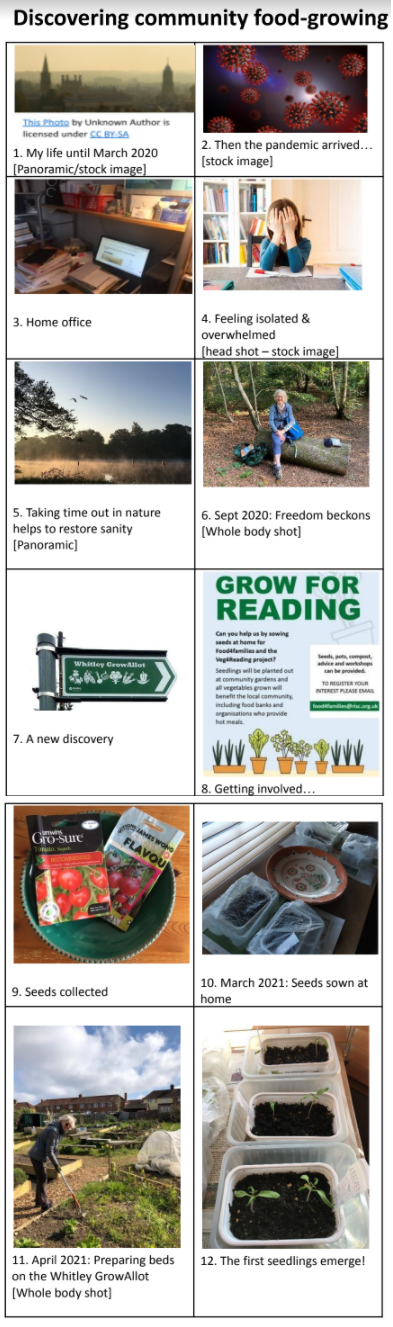

4. Photostories - Watering your young seedling

Now, that your seed is planted. It’s time to water your young seedling and give it some more attention. We will do this by creating a photostory of your seedling - carefully examining your idea more closely and starting to build a first soft and fragile representation of your story.

Photostories are a way to represent certain issues or practices through photos. This can be done either individually or in a group to answer a specific question or tell a particular story. You can use your rich picture to identify key issues, events and impacts, and how they could be visually represented, that could be strung together into a more linear narrative. The idea is to take photos and/or draw pictures of your linear narrative which you then compile into a sequence and sometimes with additional written text to add to the visuals. A photostory can be really helpful as it enables you to quickly produce and share your perspective with a group or wider community and to start a discussion.

5. Video Narrative - Harvesting the first crop

You’ve done so well taking care of your seedling that now it’s already time to harvest the first crop - the first video representation of your story!

We have created your own step-by-step guide for creating your own video narrative later in this course. But here’s a first example that shows you how Paula developed her photostory further into a video narrative:

6. Journalistic video approach - Sharing your harvest with others

After you’ve started harvesting your first video stories, you can share your harvest with others and invite them to take part. This is done by creating a journalistic video. This means interviewing someone as part of your video and inviting their perspective in sharing part of your story with them.

This approach is especially useful when you want to share and highlight someone else’s perception, experience or knowledge on a specific issue. It’s a way of storytelling that uses a set of questions to investigate a specific topic. This approach depends on the storyteller’s ability to conduct a good interview to be able to share other’s point of view. Here is a brief video tutorial illustrating what we mean by conducting a good interview:

Some of the tools shown in this video might be useful for the digital stories that you are going to produce, too. If there is someone else in your community who is not participating in the course, but who’s perspective you’d like to include, this is how you might go about including them.

7. Participatory Video - Growing your seeds together with others

One of the main differences between a journalistic video and a participatory video is how much agency your other community food growers have. In the case of a journalistic video, you’re inviting them to share their perspective, to eat from your harvest, but they don’t have much agency in terms of how the harvest comes to be. Participatory video in contrast is where you share seeds from your plant to your fellow gardeners, you all grow something together, taking turns watering and caring for your plants and then cooking a big meal out of it together.

In other words, the aim of the participatory video approach is to bring a group or community together to explore issues and concerns or tell their story in a collaborative way. Creating a video here is a way to bring people together and engage in a process of exploring an issue in depth. Participatory video can also help to empower marginalised communities and help give a voice to their stories and concerns. This video tutorial has a good explanation of participatory video: