Unit 5: Improving accountability in safeguarding

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

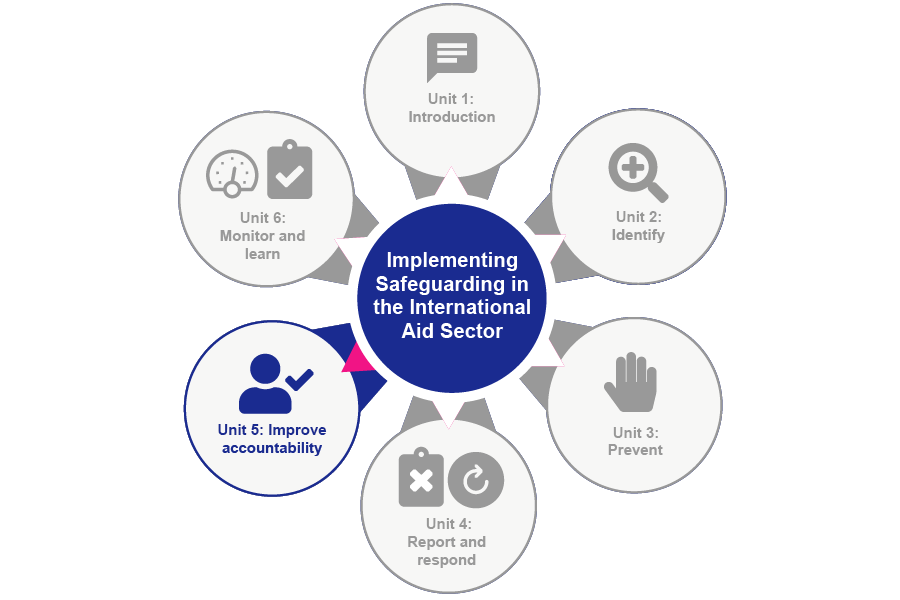

| Course: | Implementing Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector |

| Book: | Unit 5: Improving accountability in safeguarding |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 12:40 PM |

Introduction

Safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility. Accountability is at the heart of safeguarding. Many of us are all too familiar with instances where perpetrators of abuse are exonerated from any responsibility or liability for their misconduct.

Therefore, communicating to all stakeholders what to expect from us, and how to be heard when expectations are not met, or harm is caused by someone who works or represents our organisation is essential. As such, we are accountable to the communities we work with and serve, to those who represent us, to our donors, partners, regulatory bodies, and national and international agencies.

In this unit we look at how to prioritise safeguarding in accountability mechanisms across an organisation. Safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility, not just the focal lead, and by sharing this responsibility we can better promote accountability and keep people safe. Accountability is at the heart of safeguarding.

5.1 How to improve accountability in safeguarding

© phototechno / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Twenty years ago, the aid sector was primarily focused on a project or programme being delivered to the targeted community on budget and in a timely and effective manner.

Since 2000 however, with the development of the first Sphere Handbook (PDF), accountability to affected populations has become an equally important focus of aid. The need for this new focus was heightened by the confused response to the Asian Tsunami in 2004, where the lack of accountability to affected people led to poor outcomes for many, despite exceptionally high levels of funding.

As an article on the international aid response to the Tsunami commented:

Why did the exceptional funding not lead to an exceptional response? … The international humanitarian community was trying to do the wrong thing: implement its own set of agendas rather than put the affected community in the driving seat.

This lack of local ownership leads to a dearth of accountability and quality in humanitarian response (Telford & Cosgrave, 2007).

This lack of engagement and accountability to affected people led to changes in the international aid sector as accountability to affected people became more important to donors and aid agencies.

Since 2018, there has been a renewed focus and commitment to tackle SEAH in the aid sector. Organisations need to be transparent and accessible in their work with affected populations, so that where harm is caused by staff, affected people should know how to hold the organisation to account.

Organisations are guided by quality and accountability initiatives, such as:

- The Core Humanitarian Standards (CHS) that describe essential elements for principled, accountable and high-quality humanitarian action.

- The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), which includes 6 Core Principles that should form the basis of all codes of conduct and the Minimum Operating Standards.

- Sphere’s humanitarian charter and minimum standards, which provides an operational framework for accountability in humanitarian emergencies.

These quality and accountability initiatives seek to standardise interventions across organisations and should be included in organisations’ HR manuals, safeguarding policies, and strategies across all aspects of their work.

However, many believe there is still a lot of work to be done in the sector – see the example in the activity below.

|

In January 2021, Sarah Champion MP, speaking as Chair of the UK Parliament’s International Development Select Committee said: We must stop this patronising attitude of aid giants imposing aid programmes on beneficiaries and local groups without including them in the design. It only builds distrust and gives an ‘us and them’ picture to the people that the aid sector is meant to support and also the abusers looking to exploit. (Source: Reliefweb: House of Commons International Development Committee: Aid beneficiaries continue to be abused by aid workers) |

|

Activity 5.1 Can you think of any examples of where accountability standards have improved the implementation of safeguarding? Make notes in your learning journal. |

![]()

If you want to learn more about accountability read the following resources:

- Core Humanitarian Standard CHS

- The essential linkages between Accountability to Affected Populations (AAP) and Prevention of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA) (PDF) The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC)

- The Sphere Handbook (PDF)

Accountability to whom?

Accountability in the aid sector has two dimensions: internal and external.

Internal accountability is how we and our organisation understand our roles and responsibilities and meet the standards of performance we set for ourselves. This involves clear job specifications for all members of the organisation (for staff, managers, implementing partners), regular training to update knowledge and skills, and performance evaluation to ensure we are meeting expectations and responsibilities.

Staff members at all levels of the organisation need to understand their rights and obligations linked to the creation and maintenance of safe and healthy workplaces and living environments (often known as a ‘safeguarding culture’). You will remember that it is everyone’s responsibility to provide a safe environment in our organisations by promoting a clear code of conduct, and managers have a particular responsibility to do this (refer to Principle 6, IASC PSEA 6 Core Principles).

External accountability includes our responsiveness to those we work with and for, to our donors and supporters, and to the public at large. In today’s social media world, organisations have to be nimble in responding to negative media stories that can very quickly damage their reputation and erode the trust of donors and the public.

Accountability to donors

Organisations who receive financial support through grants have to account to donors by way of regular bookkeeping, accounting and reporting.

Accounting for the behaviour of our staff and those we represent is no different, and indeed has been prioritised by donors in the last few years as a non-negotiable norm. Accountability to donors is demonstrated through data collection and the existence of usable and trusted safeguarding systems.

For example, systems need to be in place for facilitating whistleblowing, reporting SEAH incidents, and usable and effective referral pathways for survivors.

Our work can make for confusing chains of responsibility and accountability. For example, our organisation might have robust safeguarding policies and processes in place, but those we partner with may not understand their roles and responsibilities, which could prove a safeguarding risk for our organisation.

It is the aid sector’s responsibility to make sure their partners down the delivery chain are as accountable and well-functioning as possible and to look to improve weak links.

Donors can require a suite of policy documents, personnel and processes to be in place before signing a contract. These can include:

- Safeguarding policy.

- Whistleblowing policy.

- Code of conduct.

- Safeguarding Officer/Lead at management level.

- Clear, confidential and accessible reporting mechanisms.

- Risk register.

(Source: Resource and Support Hub, 2020)

Ensuring these are in place is part of due diligence on the part of donors to affected people. But donors often require further evidence to verify that the policy documents actually inform organisational practice rather than just sit on a dusty shelf. This makes safeguarding more robust, as well as limiting reputational damage to the donor if safeguarding breaches are uncovered.

Where breaches happen, donors can argue they did everything reasonable to ensure the organisation had robust safeguarding processes and practices in place. But if a donor feels their expectations aren’t being met, and the organisation is not meeting its accountability obligations, donors can suspend the project until such time as improvements are put in place, or they can stop supporting the project or the organisation altogether.

|

Activity 5.2 Case scenario Read the short case scenario below about Measho, a Safeguarding Lead, who has been asked to collect evidence to show a donor how his organisation’s safeguarding policies are implemented in practice. Organisation X is very pleased to have been selected to deliver a water and sanitation programme. However, the donor has asked for evidence to show how the safeguarding policies (already submitted as part of the bid) are implemented in practice. Measho is the Safeguarding Lead in the organisation. Senior management have asked him to collect evidence to satisfy the donor's request. He talks to project officers in the field, to HR, and to senior management. Measho has to decide what evidence he can use to showcase how the organisation has implemented its safeguarding effectively. Measho is happy with his selection, which he feels gives sound insights into his organisation’s safeguarding culture. Now attempt the following two quiz questions. |

Accountability from local partners

© Vladimir Kononok / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Local partners are often the closest to beneficiary communities and are therefore pivotal to accountable working. They are likely to be the first to hear of community discontent with a project, or of harm caused.

In reporting to your organisation, they can provide the necessary contextual information to help build a nuanced understanding of safeguarding risks. However, they might also have less robust accountability and safeguarding processes in place, which will need supporting.

You will need to familiarise the local partner with the commitments you have made to the donor and support the donor to help you meet these commitments. This should be done without undermining the local partner’s experience and expertise.

Regular consultation with local partners enables information sharing and facilitates discussion of the best ways to meet the needs of affected people and donors. However, you also need to build in accountability from local partners as well as your accountability to them. Challenges can be identified, and feedback mechanisms may be established together. In this way accountability can be built into collaboration and feedback mechanisms embedded in the process.

Local government may also be a necessary local partner. Whilst they might not be involved at all points, they should be kept informed, as they could have responsibility for actions after your project finishes.

Accountability to beneficiaries

Accountability to affected people is important in order to tackle SEAH in the aid sector. Where harm is caused by staff, affected people should know how to hold the organisation to account.

Accountability to beneficiaries is more complex and contested than that to local partners because of the diversity of groups involved, who are unlikely to benefit equally from your organisation’s action. But accountability to beneficiaries is also the most important form of accountability.

There can be many barriers that affected people need to overcome before becoming involved in projects and/or coming forward to make a complaint or safeguarding report that undermines accountability. These barriers may be institutional, attitudinal and/or environmental.

Institutional barriers are often more difficult to recognise. Institutions can be an organisation established for religious, educational, professional or social purposes, or they can be an established legal or other practice, such as marriage or the family. Institutions are the structures within which we live our private and public lives. Institutional barriers might stop a young woman coming forward to make a complaint about a staff member who is asking for sex in exchange for support because of the shame it could bring on her and her family.

Some individuals will have many barriers preventing them accessing support, such as being a married woman with caring responsibilities for her family (institutional and attitudinal barriers) and having no time because of water-fetching duties that can take many hours of every day (environmental barrier). You will remember from Unit 2 that such intersectionality can greatly increase vulnerability and risk to SEAH.

Attitudinal barriers are perceptions of particular groups or characteristics that can result in them not being considered or subject to stigma that prevents them accessing support. They can be cultural assumptions, gender inequalities, or because of disability or age. You explored in Unit 2 how attitudes to some groups make them more vulnerable to SEAH.

Environmental barriers are where the local context makes it difficult for some people to access support. For example, living remotely from the hub of a project or not having the time makes accessing support difficult. Similarly, having no spare time to become involved in a project (such as during harvesting season) is another environmental barrier to accessing support.

Some individuals will have many barriers preventing them accessing support, such as being a married woman with caring responsibilities for her family (institutional and attitudinal barriers) and having no time because of water-fetching duties, which can take many hours of every day (environmental barrier). You will remember from Unit 2 that such intersectionality can greatly increase vulnerability and risk to SEAH.

How beneficiaries can get involved

Ensuring accountability to beneficiaries can be facilitated by supporting local communities’ abilities to monitor project delivery and to hold those with power to account. Such initiatives can be influential in encouraging affected people to speak up, particularly regarding SEAH.

|

Activity 5.3 Kenya: Water without walking for miles Watch the video above, Kenya: Water without walking for miles, which looks at how a local community was involved in monitoring the delivery of development projects. Then in your learning journal consider the following questions:

|

Hopefully you have reviewed practices in your own organisation and identified if there are any improvements that can be made.

5.2 Guide the development of accountability processes and tools

Developing an accountability strategy in organisations is important for building an accountability culture and creating the necessary accountability processes and tools.

An accountability strategy

© Enis Aksoy / Getty Images

An accountability strategy can help promote an accountability culture and guide the development of accountability processes and tools in our organisations.

There are three areas that comprise an accountability strategy. These are:

- Taking account.

- Giving account.

- Being held to account.

We will now look at each of these areas in turn.

Taking account

This is where we seek to understand the community we are working with and its local context. It means we need to assess the needs of the various groups and hear how they prioritise their needs. We also need to tackle the power imbalances around gender, age, disability and sexual orientation, and ensure the interests of these groups are heard. By taking into account these differences, our safeguarding measures are more likely to be successful through being more inclusive.

Giving account

This is where we give account of ourselves and our actions to affected communities, local partners and donors. Decisions need to be made as to how best to communicate with these different stakeholders and what the messages should be. This is the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of communication, which will be different for different stakeholders within the confines of confidentiality.

Stakeholders such as donors and local partners need to be kept up to date with decisions taken on how an organisation is responding to a serious safeguarding report. Organisations may also have to give account to the elders of a beneficiary community or survivors (and their families) of sexual or other forms of misconduct by their staff or partners.

Being held to account

This is where we are held to account for the behaviour of our staff and all those who represent us. This would include how effective, relevant and timely our safeguarding measures are, including how we communicated with communities about the conduct they could expect from our staff and associated personnel. It means being held to account for fraud, corruption and SEAH by our staff and associated personnel among the communities we serve.

Effective complaints and feedback mechanisms are needed for affected people to report abuse, express their views and have confidence that action will be taken (the first course in this series, Introduction to Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector, gives further information on this).

By asking the following three questions at all stages of a project and when meeting with affected populations, you should be able to take steps to improve accountability and safeguarding:

- What do we need to take account of?

- What do we need to give account of?

- What are we held accountable for?

(Source: Humanitarian Leadership Academy (n.d.))

5.3 Community engagement

© Fizkes \ Dreamstime.com

An accountability strategy is important because it is an ethical approach that supports human rights, particularly the right not to be discriminated against, the right to life with dignity, the right to receive humanitarian assistance, and the right to protection and security.

An accountability strategy:

- Improves the performance of aid, its integrity and transparency.

- Lessens corruption, fraud and conflict.

- Builds trust.

Participation of affected people in all these areas is essential to reinforcing the rights of communities to be consulted and to be involved in actions to support them. Participation can also reveal problems with a project. Perhaps there were flaws in the design stage (the needs assessment), the implementation stage (certain interests were overlooked), or in the evaluation (marginalised voices were not heard). Thus, community engagement is fundamental to an effective accountability strategy.

Effective community engagement is also at the core of safeguarding. It can build trust, confidence and processes for affected people to report instances of harassment, exploitation or abuse. Before, during and after the implementation of any project there should be regular engagement with the community.

A wide range of participatory tools can be used to facilitate engagement, such as meetings, household surveys, interviews, focus groups, theatre and video tools, which produce both quantitative and qualitative data.

In Unit 3 we looked at The Ladder of Participation, where power between organisations and children/community members who benefit from programmes can be shared for better outcomes. Participatory approaches empower participants and those affected by an action to frame the action in ways that are meaningful to them. This means that organisations are more downwardly accountable to beneficiaries.

Participatory approaches help address power imbalances, giving a voice to affected people who might otherwise struggle to talk about an issue. They can help children, the elderly, women, the disabled and other marginalised groups overcome institutional, attitudinal and environmental barriers for a more inclusive dialogue. They also help participants develop skills and confidence to articulate their experiences and opinions.

Participatory approaches have several advantages for safeguarding, as they help develop more culturally appropriate, contextually sensitive and relevant research and data collection methods. They can also build a more conducive environment for safeguarding disclosure.

|

Activity 5.4 Overcoming challenges Consider the following questions and keep a note of your responses in your learning journal:

|

A participatory method using photography

© Aleem Zahid Khan \ Dreamstime.com

Participatory approaches can use very creative methods. Examples include drawing maps, drawing pictures, role playing, giving people cameras to take photos or making videos.

They can help affected people understand their thoughts and feelings and provide a means to express and communicate them in ways they feel comfortable with. Establishing good communications with an affected community can reduce harm caused by the community.

Effective communication can also boost the implementation of safeguarding, as affected people have greater confidence to report harms caused by staff members.

Now read about the participatory photography method used by Christian Aid to help adolescent girls in a region of Kenya tell their stories.

The photographs provide a means for the girls to understand and acknowledge their experiences and to communicate them powerfully, where they would probably have found it hard to put their experiences into words.

Their photographic testimony enabled the project team, local leaders and communities, as well as their families, to better understand their experiences and daily challenges. This might also help the girls identify and express their needs and wishes and give them greater influence over decisions made to support them.

Tools for community engagement

|

Activity 5.5 The Experience Map To help you explore new ways of engaging with beneficiaries, NESTA – a UK innovation foundation, has a collection of social engagement tools with short videos explaining how to use them. One such tool is the Experience Map. Watch the video below, which helps you view your work through the eyes of beneficiaries/affected populations. This is especially useful because it highlights at which points beneficiaries come into contact with your staff and partner personnel, the level of engagement, and how they feel about what you are doing. By identifying these contact points and exploring the interactions, organisations can better identify risks and implement effective safeguarding measures. Consider how useful they would be for your organisation. |

![]()

If you would like to learn more, you might find these other NESTA tools useful for collecting inputs from communities:

- Storyworld (link coming soon)

- People shadowing (link coming soon)

- Interview guide (link coming soon)

|

Activity 5.6 Community engagement (poll) Reflect on the three statements that follow and respond using the poll function (all responses are anonymous). In my organisation, community engagement is not as systematic and inclusive as it could be, which can undermine safeguarding.My organisation would be open to trying new and different participatory methods to engage communities, which could boost safeguarding reporting.If I were given appropriate training, I would use new and different participatory methods in my work to engage communities to strengthen safeguarding reporting.Community views should inform the development of safeguarding policies, processes and mechanisms across organisations. In this way a 'speak-up' culture can be promoted. |

|

Activity 5.7 Promoting accountability Watch the video below, a community-based Safeguarding Visual Toolkit, which is an adaptable toolkit designed to assist humanitarian and development agencies communicate key safeguarding messages. Consider how you could use a visual tool with a community you serve (as a presentation, a poster, a training event, an awareness raising activity, etc.). Part of the work we do is to strengthen the knowledge and information of the people that we serve – not only in terms of what our organisation does but also how they can be included in what we do and how to hold our organisational staff to account for what they do, particularly around the abuse of power leading to misconduct. When we are working with children or vulnerable adults, we must ensure information on how to hold our organisational staff to account is accessible to men, women, boys and girls in the community. It’s really important that we ensure that the materials we develop should be done in collaboration and consultation with communities to ensure they understand what behaviour they can expect from us, our staff and our partners and how to hold us to account if exploitation, abuse and/or harassment occurs. The Safeguarding Visual Toolkit is available in a number of languages. This provides an extensive list of translations from which you can link to the translated resource in different formats. |

5.4 Community-based complaints mechanism

Complaint handling is essential for safeguarding and is a key area of beneficiary accountability.

An organisation might have a detailed and comprehensive complaints policy and process, but unless it is readily accessible to affected people it is not fit for purpose. There is a need to build bottom-up participation in the design of accountability processes that are culturally, age and gender appropriate if SEAH reporting is to increase.

Community members need an accessible mechanism to raise concerns when they occur or are suspected. A community-based complaints mechanism (CBCM) is an approach that is grounded in community input. This means that it is culturally and gender sensitive, and contextually appropriate. It has a number of roles as shown in the diagram below.

Whilst CBCMs are primarily about good programme management and not specific to SEAH, an increase in SEAH reporting could be a powerful way to gauge the success of a CBCM. We know that SEAH is happening, and an increase in SEAH reporting would mean that the CBCM is accessible and working for the most vulnerable and at risk.

Similarly, a lack of SEAH reporting doesn’t mean that there is no SEAH happening. It could mean that the mechanism currently in place isn’t sufficiently accessible and/or sufficiently rooted in the community and/or trusted by the community with the fear of reporting still high.

A CBCM is preferable to individual organisations having their own complaints procedures. Whilst the latter approach provides accountability for the organisation, it is likely to be confusing to affected people who may have contact with many organisations, each with their own complaints mechanism. This could seriously undermine SEAH reporting.

Collaboration between participating agencies, including the host government, to build a CBCM that is particularly sensitive to safeguarding reporting is best practice and establishes clarity and support for making complaints.

![]()

If you are interested in reading more about Community-based complaints mechanisms, read the following document:

© Rawpixelimages / Dreamstime.com

|

Activity 5.8 Case study – creating a CBCM Read the following case study which explores the creation of a community-based complaints mechanism (CBCM). Note in your learning journal what next steps you would take within the confines of confidentiality and procedural fairness. Your organisation meets with different representatives of the local community to discuss how to establish a CBCM. The feedback and complaints mechanisms were kept as simple as possible and produced through several consultations. They established many different channels for reporting, including a confidential email address, short messaging service (SMS), and a suggestion box for those unfamiliar with online technology. Once a feedback or complaints report is made, it is triaged (reviewed and prioritised) and action by the organisation is initiated by the safeguarding committee. You are the safeguarding focal person for your organisation and have received two safeguarding reports over the past month regarding the misconduct of your staff. The safeguarding committee is still discussing next steps. However, you are experiencing a lot of pressure from various stakeholders to disclose information. The Subjects of Complaint (the persons who have been complained about) want to know who made the complaint. Survivors and their families want to know what has been done about the reports and have various ideas on how to ‘punish’ the staff members being complained about. The government partners hear about it and want the complainant to come forward to make a police report. The donors have been informed and want to get more involved with the investigation. |

5.5 Mainstreaming safeguarding through all communications

Safeguarding should be mainstreamed through all organisational communications. This promotes ownership of a safeguarding agenda across all departments of an organisation, as well as all the organisations we engage with.

© GOCMEN / iStock / Getty Images Plus

If we put safeguarding at the centre of all our work by ensuring inclusion and participation of our beneficiary groups, the delivery of our programmes will be much safer for all persons concerned. This includes mainstreaming safeguarding in advocacy, campaigning, media and marketing. In this way we promote ownership of a safeguarding agenda across all departments of our organisation, as well as all the organisations we engage with.

To do this, organisations need to demonstrate strong leadership and direction in promoting and modelling a safeguarding culture. For example, by showing how safeguarding is fostered in the workplace and in staff training with a clear focus on prevention and early intervention. Staff can be trained to recognise the signs of abuse/neglect and empowered to act on concerns.

When working with beneficiaries, supporting them in understanding their rights and becoming more confident in promoting them can reduce opportunities for abuse. Providing a trusted point of contact for people to make disclosures can lead to earlier intervention. Engagement with wider social networks through online instant messaging tools can build resilience, mitigating against abuse.

However, online messaging carries its own confidentiality risks, which need to be considered carefully. People with disabilities may report through drawing, through actions, and through their family and friends who have personal ways of communicating with them.

Safeguarding can be made more robust when engaging with other organisations by promoting open dialogue where the views, wishes and needs of beneficiaries are heard, respected and acted upon across the partnership.

Engaging beneficiaries in safeguarding

![]()

Watch the video below to hear about some of the ways that Plan International and its consortium members have supported the voices of boys and girls to ensure the organisation is held to account particularly during Covid-19.

Safeguarding in media and marketing

In media and marketing advocacy campaigns, case studies are powerful tools to communicate messages and organisational success. But using them comes with risks for beneficiaries, which need to be assessed and managed.

![]()

Watch the video below in which the organisation, Witness, discuss how to ensure that ‘do no harm’ safeguarding measures are used to reduce the risk of re-traumatising survivors and to ensure an empowering process.

Trigger warning: the speakers in the video are survivors and activists.

Below is a checklist to support case study development and to safeguard those involved:

- Undertake a risk assessment.

- Make sure you are telling a story the beneficiaries are comfortable with you telling, and that you are not disclosing any confidential information.

- Seek written informed consent from the individual or community. You will need to think about how to keep a record of their consent as sometimes written consent is not possible.

- Ensure that the case study includes no names or other personal identifiers.

- Tell the individual or community how the case study will be used and disseminated as part of gaining their consent.

(Source: Witness, 2021)

The use of language is critical to convey an organisational message. It should be supportive and non-judgmental and should not put anyone at risk. For example, throughout this course we have spoken of ‘survivors’ of SEAH rather than simply ‘victims’, as the term ‘survivor’ is more likely to encourage individuals to seek help when they need it.

When communicating with those gathering case studies, including journalists, it may be necessary to explain the terms you use and encourage them to do likewise, in order to foster an empowering positive change.

When engaging with the media and building marketing campaigns, images and video are often used because these are more impactful and engaging than just words. But care should be taken when featuring children, vulnerable people or beneficiaries, as harm may result.

5.6 Unit 5 Knowledge check

The end-of-unit knowledge check is a great way to check your understanding of what you have learnt.

There are five questions, and you can have up to 3 attempts at each question depending on the question type. The quizzes at the end of each unit count towards achieving your Digital Badge for the course. You must score at least 80% in each quiz to achieve the Statement of Participation and Digital Badge.

5.7 Review of Unit 5

© Feodora Chiosea / iStock / Getty Images Plus

In this unit we learnt about the importance of accountability for safeguarding, most especially accountability to donors, local partners and beneficiaries.

We considered what an accountability strategy is and how to engage communities more effectively to build one. We explored participatory methods which are more inclusive of all beneficiary voices and how these can be involved in the development of a community-based complaints mechanism.

In recognition that safeguarding accountability is a cross-organisational responsibility, we looked at safeguarding in our advocacy, campaigning, media and marketing.

Finally, you considered case studies as powerful tools to communicate messages and organisational success in media and marketing, and how to manage the safeguarding risks for beneficiaries.

|

Learning journal Before you move on to Unit 6, reflect on your own learning so far. Consider the following questions and respond to the questions in your learning journal.

|

Now go to Unit 6: Learning and organisational culture.

References

Reliefweb (2021) House of Commons International Development Committee: Aid beneficiaries continue to be abused by aid workers, Online. Available at Reliefweb (Accessed 9 September 2021).

Resource and Support Hub (n.d) Safeguarding matters, Module 2, Online. Available at RSH (Accessed 23 June 2021).

Telford, J. and Cosgrave, J. (2007) The international humanitarian system and the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunamis, Online. Available at Wiley online library (PDF) (Accessed 9 September 2021).