Unit 3: Reporting, responding and investigations

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Leadership in Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector |

| Book: | Unit 3: Reporting, responding and investigations |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 3 March 2026, 9:07 AM |

Table of contents

- 3.1 Introduction

- 3.2 A culture of silence

- 3.3 What are the next steps?

- 3.4 Risk assessment

- 3.5 Undertaking internal investigations

- 3.6 Investigation principles

- 3.7 Roles and responsibilities

- 3.8 Managing and investigating microaggressions

- 3.9 Importance of accountability

- 3.10 Learning from past mistakes

- 3.11 Protecting whistleblowers

- 3.12 Learning reviews

- 3.13 Webinar 2

- 3.14 Unit 3 Knowledge check

- 3.15 Review of Unit 3

3.1 Introduction

In this unit we look at methods of reporting, how organisations should respond, protection for whistleblowers and carrying out administrative investigations.

This course explores the relationship between leadership and safeguarding within organisations. It facilitates a strengths-based approach to leadership in order to keep people safe within organisations as well as those they have contact with in the work that that they do, and to influence wider change across the sector

So far, we have looked at leadership in safeguarding and the importance of a safeguarding culture to bring about behavioural change.

We discussed that safeguarding in organisations should not be viewed purely from a compliance point of view.

By looking at the typologies of organisational culture, organisations can consider where they are on their safeguarding journey:

- Pathological – why do we need to waste our time on safeguarding issues?

- Bureaucratic – we have systems in place to manage safeguarding incidents.

- Proactive – we are always on the alert and thinking about safeguarding issues that might emerge.

- Generative – managing safeguarding is an integral part of everything we do.

(Adapted from work on patient safety cultures, London School of Health & Tropical Medicine)

3.2 A culture of silence

One of the challenges for aid agencies is challenging the culture of silence.

This could be related to discomfort about the issues related to abuse and harassment, or a culture where those in leadership are all of the same gender and/or type, leading to those who are different (due to gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, ability, etc.) not being listened to.

Sometimes managers, who are also safeguarding focal points, may be so overwhelmed with other issues that they do not have the resource capacity to manage safeguarding concerns, which require good analytical and monitoring skills, as there is insufficient internal resourcing for this work.

The other reason could be that organisations are much more inclined to make decisions in their best interest, or in the best interest of those who have perpetrated the misconduct, rather than what is a survivor-centred approach. Organisations may have failed to ensure a robust follow-up on cases or, more importantly, a lack of transparency with complainants on how the cases have been managed.

Indeed, as part of their due diligence processes, organisations should regularly, and proactively, publish the number of concerns reported, how they were followed-up and what the outcomes were, in an anonymised fashion, to demonstrate transparency and encourage increased reporting.

Experience has shown that early engagement with staff, associate personnel and partners on developing confidential and safe internal reporting mechanisms with the Board and/or an external oversight has been helpful. Many organisations may have external whistleblowing mechanisms.

However, are these external agencies equipped to deal with safeguarding concerns or are they better placed to deal with other concerns, such as bribery, corruption or conflict of interest?

Although there are some countries where workers may have access to an external, independent ombudsman to deal with workplace situations, such mechanisms may not be equipped to manage or investigate the safeguarding concerns of children and vulnerable adult beneficiaries who may not know how to access such mechanisms. Organisations that offer generic email addresses must ensure confidentiality and take appropriate next steps once reports are received.

|

Activity 3.1 Barriers to reporting Read the two articles below and consider the questions that follow. Make some notes of your responses in your learning journal: The readings contain details some people might find distressing.

What do these reports identify as barriers to reporting? How can organisations foster trust in reporting mechanisms? |

3.3 What are the next steps?

Leaders in international organisations must be clear and decisive when taking next steps.

Such next steps may include:

- Setting up a safeguarding committee or organising one specifically to deal with safeguarding concerns.

- Deciding on who should be part of this committee to streamline decisions being taken. Ensuring that there are regular and co-opted members.

- Communicating with stakeholders (donors, regulatory bodies, staff and partners) without divulging confidential information.

- Risk assessing next steps including undertaking an internal investigation and/or reporting to law enforcement.

|

Activity 3.2 Handling safeguarding concerns Read the RSH flowchart resource, Case handling for civil society organisations (CSOs) in Nigeria. Use it to review how things work in your own organisation

|

3.4 Risk assessment

The safeguarding or complaint handling committee should undertake a risk assessment when managing safeguarding concerns.

Sometimes unconscious bias may lead to decisions being taken that side with the perpetrators rather than with the survivor, since there are often concerns related to damaging someone’s career over potentially false claims (which do happen but remain rare).

Therefore, it’s important to remember that decisions taken should be survivor centred (i.e., what is in the best interest of the survivor rather than for the perpetrator(s) or organisation which they represent) to ensure that the needs of survivors/victims are being seen to, without derogating from the organisation’s duty of care to take appropriate steps to reduce risk to other staff, children or vulnerable adults.

Tools such as a risk assessment template are helpful to ensure that all risks have been identified and mitigation measures have been put in place.

![]()

Watch the video above on how to complete a risk assessment.

|

Having watched the video on completing a risk assessment, reflect on what are some of the key risks when managing safeguarding concerns and next steps. |

3.5 Undertaking internal investigations

The Safeguarding Lead should assess all safeguarding reports, in consultation with the safeguarding or complaints handling committee, as to whether a safeguarding investigation should be convened.

Investigations will be convened based on the connection of the Subject of the Complaint to the organisation and the severity of the alleged incident and the harm that has occurred. It is good practice for this committee to have an oversight over the investigations process by setting the terms of reference for the investigations team. It is expected that a safeguarding investigation will be convened as a matter of course where the three main criteria are met.

There are times when law enforcement is already involved, and an internal investigation is not appropriate as evidence may be tampered with.

In many contexts, safeguarding concerns are not considered criminal in nature but rather violate an organisational Code of Conduct and related policies. Therefore, an impartial, internal investigation should proceed.

If the alleged perpetrator is a staff member, suspension or administrative leave might be necessary pending the outcome of the investigation, based on the following considerations:

- The alleged perpetrator has been accused of serious misconduct, which, if proven, would result in summary dismissal.

- There are grounds to believe that the alleged perpetrator might pose a risk in the workplace or tamper with evidence.

- The alleged perpetrator’s continued presence at work might prejudice the investigation in some way, for example, if there is a risk that they might intimidate survivors or witnesses. Note that survivors of SEA may not be in a position to take leave because they have not got the annual leave to take.

- The alleged perpetrator has acted in a violent manner or has threatened violence.

- The alleged perpetrator has been accused of serious bullying or harassment.

- The matter under review is of a highly sensitive nature such as an incident of sexual assault.

A suspension is not a declaration of guilt. In case an alleged perpetrator is suspended, the organisation should communicate this message clearly to the individual as well as other staff members who are aware of the suspension.

![]()

Want to find out more?

For further guidance on undertaking investigations, follow the link below:

3.6 Investigation principles

When undertaking investigations, an Investigations Plan should set out the following steps:

- Background of the concern.

- Objectives of the investigation.

- Allegations made and the corresponding breaches in organisational policies and Code of Conduct.

- Agreed roles and responsibilities.

- Principles of the investigation.

- Investigation risk assessment (e.g., safety, security, wellbeing).

- Any obstacles to the investigation (e.g., legal, practical constraints).

- Potential list of witnesses and evidence collated and still to be collated.

When undertaking investigations, it’s important to ensure the principles of investigation are upheld at all times. They include the following:

Confidentiality

All parties have a right to confidentiality. In some instances, it will not be possible to guarantee confidentiality, for example, where referral is made to national authorities by the survivor or the survivor’s family. Information will only be shared on a ‘need to know’ basis, the parameters of which should be established at the planning stage.

The identity of those involved should only be disclosed on an authorised basis where referral to national authorities is indicated. Within the disciplinary process, it is not necessary or desirable to reveal the identity of the complainant, survivor or other witnesses.

Records should be stored securely to avoid accidental or unauthorised disclosure of information. Complainants/survivors/witnesses may want to remain anonymous during the investigations and as such their identities should not be revealed to perpetrators or to other witnesses. Such complaints should be provided the same importance as other complaints where survivors have been identified.

Professionalism

Complaints are treated with respect and in a fair and equitable manner. All those involved in the investigation must have received investigation training and have the knowledge and skills to fulfil their responsibilities. Only trained investigators should investigate allegations of SEAH.

Thoroughness

Investigations must be conducted in a diligent and rigorous manner to ensure that all relevant evidence is obtained and evaluated (including evidence that either supports or refutes the complaint).

Objectivity and impartiality

Evidence to support and refute the allegation should be gathered and reported in an unbiased and independent manner. It is essential that investigators have no personal or professional interest in the people implicated.

Planning and review

This ensures that investigations are planned, systematic and completed according to agreed timeframes.

Respect for all concerned

Including the survivor and the Subject of the Complaint. All those concerned have the right to be treated with respect and dignity and to be kept informed of the progress of the investigation.

Timelines

It is in everyone’s interest that investigations are conducted as quickly as possible without compromising quality. A number of factors (communication systems, travel, distance, etc.) will influence what is a reasonable timeframe. As a general rule, investigations should be completed as soon as possible (i.e., final report submitted) within 30–45 days of receipt of a complaint.

Working in partnership with other interested parties

In some cases, other contracted NGOs might be implicated in the complaint. In such instances, consideration needs to be given to conducting a joint investigation if staff at both organisations are implicated, in the interests of sharing relevant information and preventing the need for repeated interviews.

Increasingly donors and regulatory bodies are becoming more involved in survivors, and may decide to refer to national authorities where they are already involved. For mandatory reporting issues involving children, determine the best interest of the child when making mandatory reporting decisions

Needs of survivors, witnesses and the Subjects of the Complaint

The needs of survivors and witnesses are paramount in the investigation process and must be constantly addressed and prioritised over other considerations. While the organisation may not be able to guarantee safety, it is essential that a survivor/witness plan is developed and reviewed. The survivor/witness must be advised as to the limits of the organisation’s capacity to protect them when ‘informed consent’ is sought.

Welfare needs would include referrals to healthcare providers and psycho-social support. It’s important to note that this is the responsibility of the organisation and therefore the investigating team should check that these needs have been met.

Medical intervention should be arranged to promote the witness’ health and wellbeing, for example, to treat injuries or sexually transmitted infections. Where there is a report of sexual abuse within the previous 72 hours, the survivor should be referred immediately if medical treatment for HIV post-exposure or emergency contraception is to be effective.

Psycho-social support should be provided to witnesses to deal with fear, guilt, shame, etc. via access to support groups and/or crisis counselling. Referrals should also be made to legal or judicial systems if the survivor should wish to do so, upon which the organisation should hand over evidence as required to those investigating criminal offences.

![]()

Want to find out more?

For further information on investigation training, follow the link below:

CHS Investigator PSEA training and qualification training scheme

|

Activity 3.3 The principles of investigation Choose three of the principles described above and note in your learning journal how you would apply them when managing safeguarding concerns. This might be a topic you need to discuss with others in your organisation. Are there principles you could do more to strengthen? |

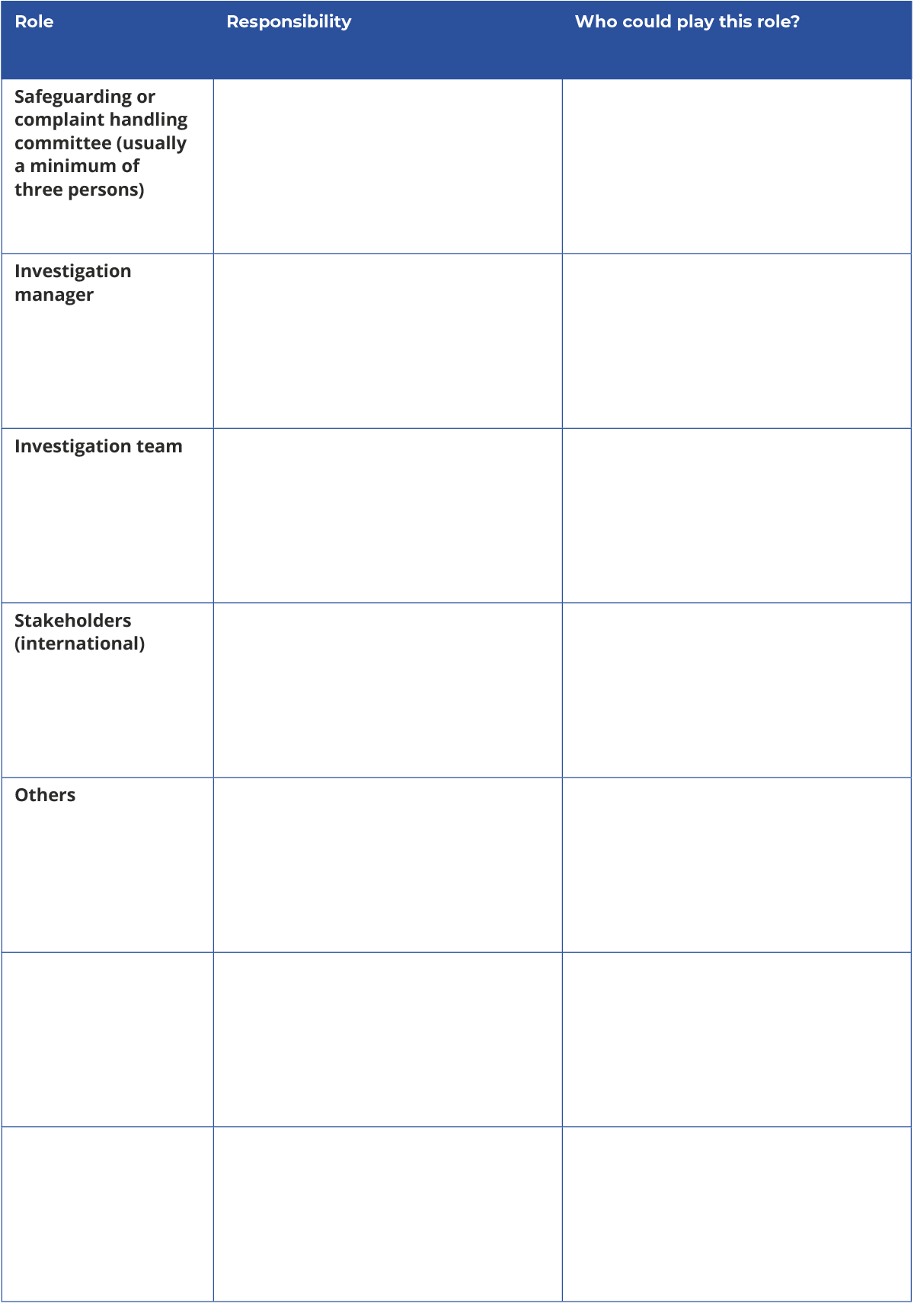

3.7 Roles and responsibilities

When undertaking internal administrative investigations, it’s important to be clear about roles and responsibilities. This next activity is an opportunity to make sure you know where responsibilities lie in your organisation – or clarify them if you are unsure.

|

Activity 3.4 Who is responsible? Look at the template below. Consider who has responsibility for the various roles listed and who could fill this role. You can add roles where relevant. Use this writable PDF version of the template which you can type into and then save it and/or print it.

(Adapted from CHS Alliance Management Investigation Checklist) |

|

Activity 3.5 Case study – next steps Microaggression is a term used for commonplace daily verbal, behavioural or environmental slights, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative attitudes toward stigmatised or culturally marginalised groups. Read the case study of a workplace situation below and consider the questions below noting your responses in your learning journal. Case study Sally, the only female manager in the programmes team, reports to the Safeguarding Lead that she experiences microaggressions from her line manager Juan, the Programmes Director. She says that every time she highlights any safety or programmatic concerns, he chooses to give her angry looks or ignores what she is saying, choosing instead to inform her that some team members have complained to him about her. He just wants everyone to get on with everyone. He is a high-profile senior staff member who is often seen as the public face of the organisation and is very well-liked by others. Sally feels undermined and disrespected in her role – she believes that she is being pushed out of the organisation because she is a woman of colour.

|

![]()

Want to find out more?

For more information on this topic, follow the links below:

GSIF Managing Investigations – Tool 1: Case studies for Leaders

3.8 Managing and investigating microaggressions

![]()

Watch the video above, in which Rebecca Dempster from Resileo provides some coping strategies for those managing microaggressions in the workplace

Intolerance for workplace bullying and harassment is becoming more and more common place in the sector as we build upon an organisational ‘zero tolerance’ against all forms of harm, including bullying and harassment. You’ll remember we touched on the speaking-up safeguarding culture in Unit 2.

Research indicates that by encouraging people to be authentic (for instance, by having them think and write about a recent situation when they were able to be who they are at work) they are more likely than those in a control condition to speak up. Participants in the authenticity condition are more likely to voice their concerns about unfair procedures that imposed costs on others. In fact, 29% of them spoke up, while only 19% did in the control condition. Leaders have a responsibility to convey to those who work or engage with the organisation that they will be protected, and their opinions will be valued, if they share suggestions, opinions and concerns. By doing so, leadership can encourage those who have been mistreated to find their voice (Source: Speaking out against a toxic culture).

When investigating bullying and harassment concerns, it’s important to ensure that proper processes and investigation principles are followed. Take into account documentary evidence as well as oral evidence when investigating and draw conclusions using a ‘balance of probabilities’ standard of proof. Outline clearly which parts of organisational policies and the Code of Conduct have been breached in order to formulate allegations appropriately.

3.9 Importance of accountability

Organisations that include a ‘zero tolerance’ statement in their policy must take the following accountability into consideration.

Accountability to survivors/victims

It is important to feedback to complainants and survivors/victims what the outcomes of their complaint were. This does not necessarily mean that organisations should share the entire investigations report or provide information that is confidential.

It is also important to remember that when managing safeguarding concerns, organisations have a responsibility to carry out all steps in response, including investigations, in a fair and impartial way. It should also be mindful that it needs to survivor-focused but not survivor-led. (see RSH Tip Sheet) [link needed]

In the case of serious safeguarding concerns for example that occurred in MercyCorps, the survivor found an outpouring of support for her ordeal and some form of justice had been met when the organisation failed to take any action at all.

The survivor and/or the Subject of Complaint they could request a review of the findings of an investigation, particularly if they are of the opinion that the investigations team failed to take into account relevant evidence and information.”

Some survivors/victims still remain unhappy with the outcome (They did nothing to protect me, Cornish 2021).

Accountability to donors

Donors require organisations to inform them of the outcome of an investigation and, increasingly, redacted versions of the investigation reports and/or executive summaries are being provided to the donor. Donors too have requested organisations to review their reports if it is found that the investigations did not follow due process or consider relevant information.

A part of donor compliance also includes the publication of safeguarding reports (under the rules of confidentiality) in Annual Reports, in an effort to increase public confidence and accountability in the respective organisation as well as the wider sector (see this example from Care International).

Accountability to regulatory bodies

Most organisations working in development or humanitarian contexts may have to be registered with their respective social welfare departments or with the Registrar of Societies in their home countries. Alternatively, they may be set up as private limited companies or social enterprises working in the non-profit or private sector.

Each of these regulatory bodies will require organisations to submit financial reports on time as well as copies of organisational policies such as their Human Resources policy to ensure that labour laws are adhered you.

In the UK, organisations who work for the welfare of people (and others) may register themselves as charities under the Charity Commissions of England and Wales, Northern Ireland or Scotland.

Safeguarding concerns must be reported to the Charity Commission by way of a ‘serious reporting incident’ and failure to ensure safeguarding actions can result in regulatory or legal action taken against it. The Commission may also require complaints to be escalated to them so that they can hold organisations accountable.

3.10 Learning from past mistakes

![]()

Watch the video above to hear interviews with leaders who have learnt from past experiences, have put that learning into practice, and have been able to mitigate against other safeguarding concerns.

|

Have you had any similar experiences of learning from mistakes and putting in these lessons into practice? |

![]()

Want to find out more?

For more information on this topic, follow the links below:

Organisational Self-assessment tool

3.11 Protecting whistleblowers

There continues to be the challenge of managing tensions between keeping the confidentiality and anonymity of survivors/complainants when managing safeguarding concerns.

Organisations should make concerted efforts to improve trust in reporting mechanism so that concerns can be raised early and dealt with swiftly, thus keeping people safe. It’s important that whistleblowers are supported and are protected from reprisals, since this would challenge the culture of impunity.

Here are a few recommendations made in the CHS Alliance Whistleblower Protection Guidance:

- Have a strong and living Code of Conduct that reflects the organisation’s values.

- Develop a whistleblowing policy and other procedures and practices that influence ethical conduct.

- Promote greater implementation of whistleblowing protection provisions throughout the organisation and involve a cross section of staff to test the policy’s implementation before implementing widely across the organisation.

- Protect reporting mechanisms and the prevention of retaliation in the organisation’s internal controls, ethics and compliance systems.

- Protect those who report and speak up.

- Ensure the whistleblowing policy scope is as broad as possible and protects all who carry out functions or activities related to the organisation’s mandate.

- Ensure reporting tools are readily available and easy to use.

- Provide multiple types of channels to report.

- Provide a secure system that can offer anonymity to the complainant or whistleblower.

- Regularly update the reporter on the progress of the case.

- Clearly communicate the processes in place (reporting channels and procedures to facilitate disclosure) through promotion, regular awareness raising and training (including policy training).

- Be accountable when wrongdoing occurs.

- Ensure there are clear messages from senior management that set the tone by ‘leading by example’ and act as positive role models.

- Remove the negative connotation and social stigma associated with whistleblowing by considering using different terms, such as ‘reporters of wrongdoing’ or ‘reporters of misconduct’.

- Regularly review, monitor and evaluate the whistleblowing policy.

![]()

Want to find out more?

For more information on this topic, follow the link below: New Humanitarian article: Acting with impunity

3.12 Learning reviews

It is good practice for organisations to hold learning reviews whether there has been a ‘near miss’ or a full investigation into a safeguarding concern.

The purpose of a learning review is to:

- Identify improvements to be made to safeguard and promote the welfare of victims/survivors.

- Seek to prevent or reduce the risk of recurrence of similar incidents.

- Establish whether there are lessons to be learnt from the case about the way in which organisations can work in a safer way.

- Identify clearly what those lessons are, how they will be acted upon, and what is expected to change as a result.

- Improve internal and inter-agency working.

Learning reviews should be facilitated by someone who was not involved in managing the investigation process of the safeguarding concern. Those who were involved could either write in their feedback or be present at a meeting, where their views are elicited.

![]()

Want to find out more?

For more information on this topic, follow the link below:

3.13 Webinar 2

|

This webinar explores the issues of leadership and organisational culture that are covered in Units 1 and 2 of this course. A recording of the webinar (58 minutes) is available for you to watch below. Each of the speakers approaches the topic from a different perspective, please note in your learning journal any key points from each that you would like to take back to discuss in your own organisation. Topic: Effective management of safeguarding concerns for leaders Speakers:

Here is a downloadable version of the slides from this webinar. Further resources to support this webinar: CHS Alliance Guidelines for Investigations resource |

3.14 Unit 3 Knowledge check

The end-of-unit knowledge check is a great way to check your understanding of what you have learnt.

There are five questions, and you can have up to 3 attempts at each question depending on the question type. The quizzes at the end of each unit count towards achieving your Digital Badge for the course. You must score at least 80% in each quiz to achieve the Statement of Participation and Digital Badge.

3.15 Review of Unit 3

In this unit you were asked to reflect on why and how a culture of silence that allows abuse, exploitation and harassment could permeate in your organisation.

We explored what next steps ought to be taken when managing safeguarding concerns, including how to run robust impartial administrative investigations. We heard from leaders who shared the important lessons their organisations had learnt from ‘sex scandals’ and ‘cover ups’ and how they put in place improved measures to keep people safe.

Finally, we looked at how the growing area of microaggressions in the workplace should be recognised and must be called out.

|

From any of the learning this unit, in your learning journal, try and identify three things that you might take away from this unit the course in relation to leadership |

Now go to Unit 4: Good governance and organisational oversight.