Children with Disabilities

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Aiming Higher for the Disabled Community: Induction and Training |

| Book: | Children with Disabilities |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 10:38 PM |

Description

This section is an additional part of your safeguarding training, and covers issues specifically related to children with disabilities.

Table of contents

- 1. Statistics

- 2. The Social Model of Disability vs The Medical Model of Disability

- 3. The Equality Act

- 4. Protecting disabled children: thematic inspection report

- 5. Why are children with disabilities more vulnerable to abuse?

- 6. Attitudes

- 7. Reluctance to challenge

- 8. Dependency

- 9. Communication Barriers

- 10. Lack of Participation and Choice

- 11. Factors associated with disability or health condition

- 12. Isolation

- 13. Double Discrimination

- 14. Extended periods away from home

- 15. Lack of training and/or understanding

- 16. The Criminal Justice System

- 17. Limited education

- 18. Higher levels of bullying

- 19. DBS checks and suitability of carers

- 20. Resources

- 21. Signs of Abuse

- 22. How does a child with a disability communicate that they are being abused?

- 23. Impeding the safeguarding of children with disabilities

- 24. Protecting Children with disabilities

- 25. Case Study and Activity

- 26. Considerations during an investigation

- 27. Identifying the perpetrator

- 28. Disclosing Abuse

- 29. The impact of failures in an investigation

- 30. Additional Issues to consider

- 31. Next steps

2. The Social Model of Disability vs The Medical Model of Disability

There are two models that we will briefly consider in this chapter. They are:

- The Medical Model of Disability

- The Social Model of Disability

Please click the 'next' button to read a brief overview of The Medical Model of DIsability.

2.1. The Medical Model of Diability

The medical model of disability is based on a biomedical perspective. According to this model, disability is primarily linked to an individual’s physical body and intrinsic conditions. Here are the key points about the medical model:

Cause: The medical model attributes disability to a specific impairment or difference within the person. It focuses on diagnosing and identifying what is “wrong” with the individual.

Quality of Life: The model assumes that the disability may reduce the individual’s quality of life. Therefore, its goal is to diminish or correct the disability through medical interventions.

Treatment: Under the medical model, impairments or differences are often seen as problems to be fixed. Medical treatments, therapies, and interventions are recommended to address these issues, even when they do not cause pain or illness.

Individual-Centric: The medical model places the person at the centre, emphasizing their condition as the primary concern. However, it tends to overlook broader societal factors and barriers.

Limitations: While the medical model has its merits in providing medical care and interventions, it has limitations. It can lead to low expectations, reduced independence, and a lack of control over one’s own life.

2.2. The Social Model of Disability

The social model of disability is a perspective developed by disabled people. It emphasizes that disability is created by societal barriers, not by impairments or conditions.

Definition: The social model recognizes that disabled individuals face barriers preventing them from fully participating in society. These barriers can be physical (like inaccessible buildings) or attitudinal (such as stereotypes).

Impairment vs. Disability

Impairment: Functional difficulties in the body or mind (e.g., hearing loss).

Disability: Inability to participate due to societal barriers (e.g., lack of subtitles in a video).

Origins: Disability activists developed this model in response to civil rights movements in the late 20th century. It challenges the traditional medical model that focuses solely on impairments.

(Nurse Next Door, 2024)

2.3. Comparisons

- Imagine a wheelchair user trying to enter a building with a step at the entrance:

- Social model solution: Add a ramp to the entrance, allowing the wheelchair user immediate access.

- Medical model approach: Few solutions exist for wheelchair users to climb stairs, excluding them from essential and leisure activities.

- Consider a teenager with a learning difficulty aiming to live independently:

- Social model support: Enable the person to pay rent and live in their own home.

- Medical model perspective: Expect the young person to live in a communal home.

- Lastly, think about a child with a visual impairment who wants to read a best-selling book:

- Social model solution: Provide full-text audio recordings when the book is published, allowing equal participation in cultural activities.

- Medical model limitations: Few solutions exist within this model. (Disability Nottinghamshire, n.d.)

In summary, the social model highlights the importance of addressing societal barriers, while the medical model focuses on individual impairments. Understanding both models helps create a more inclusive and supportive environment for disabled individuals. (University of Oregon, n.d. and Sense, n.d.)

3. The Equality Act

The Equality Act 2010 puts a responsibility on public authorities to have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination and promote equality of opportunity. This applies to the process of identification of need and risk faced by the individual child and the process of assessment. No child or group of children must be treated any less favourably than others in being able to access effective services. (Blackpool Council iPool, 2024)

4. Protecting disabled children: thematic inspection report

Ofsted's Protecting disabled children: thematic inspection report highlighted that "...disabled children, sadly, are more likely to be abused than children without disabilities. Yet they are less likely than other children to be subject to child protection."

The full reports and summaries are available here. You are not required to read these as part of your training, they are here if you should wish to look at them. The link opens in a new tab.

Please click through the slides below to read the key findings of the report, taken from the summary which is available on the link above.

6. Attitudes

Attitudes and assumptions within society and amongst those working with children can lead to a view that abuse does not happen to disabled children and in turn this undermines the safeguarding of disabled children at all levels.

Attitudes about disability are also a contributory factor in the lack of reporting of abuse to disabled children. Estimates suggest that only one in thirty cases of sexual abuse of disabled people is reported compared to one in five of the non-disabled population and a Norwegian study of children being examined in paediatric hospitals for possible sexual abuse reached similar conclusions. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

6.1. Kennedy

Research by Kennedy (1992) identified beliefs that disabled children were less likely to be damaged by abuse than other children. A failure to acknowledge and promote disabled children’s human rights can lead to abusive practices being seen as acceptable. For example tying up or locking a child in a room would be recognised as abusive for a non-disabled child but may be seen as acceptable for a disabled child. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

6.2. Marchant

Marchant identified five myths encountered in relation to the sexual abuse of disabled children:

- Disabled children are not vulnerable to sexual abuse

- Sexual abuse of disabled children is OK, or at least not as harmful as sexual abuse of other children

- Preventing the sexual abuse of disabled children is impossible

- Disabled children are even more likely than other children to make false allegations of abuse

- If a disabled child has been sexually abused, it is best to leave well alone once the child is safe. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

6.3. Disability Rights Commission

Negative attitudes and assumptions can lead to institutional discrimination. An

investigation by the Disability Rights Commission revealed ‘an inadequate

response from the health service to the major physical health inequalities

experienced by some of the most socially excluded citizens: those with learning

disabilities and/or mental health problems.’ This included disabled children and

young people. Their investigation found children and young people in particular

experienced ‘diagnostic overshadowing’ – that is reports of physical ill health

being viewed as part of the mental health problem or learning disability – and so

not investigated or treated. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

6.4. Death by Indifference

The Mencap report Death by indifference found

examples of widespread ignorance and indifference throughout our health care

services towards people with a learning disability. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

7. Reluctance to challenge

A reluctance to challenge carers has been found together with a sense of

empathy amongst practitioners with parents and foster parents who are felt to be

under considerable stress. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

7.1. Precey and Smith

Precey and Smith have considered the contentious

issue of the fabrication or induction of illness in disabled children and those with

complex health needs by a parent. Parents have been known to deliberately

exaggerate the effects of their child’s impairment by falsely describing symptoms,

seeking unnecessary treatment or inappropriately using medication. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

7.2. Case Study

An advocate was asked to get involved by a local school who were worried a child was being overmedicated by his family.

The school had observed the parents struggling to manage the boy’s behaviour and particularly at the beginning of each week found the boy to be very drowsy and unable to relate to his surroundings.

This had been reported to the social worker who was not prepared to raise the issue with the family saying they had enough to contend with as it was.

The advocate eventually helped the parents see the impact that

over medication was having and got advice for the parents on managing their

son’s behaviour. (Source: The Children’s Society, as cited by Gov.uk, July 2009)

8. Dependency

Dependency on a wide network of carers and other adults is the everyday

experience of some disabled children in order that their medical and intimate

care needs such as bathing and toileting can be met. The large number of adults

involved and the nature of the care needs both increase the risk of exposure to

abusive behaviour and make it more difficult to set and maintain physical

boundaries. Some disabled children grow up to accept damaging, demeaning or

over restricting treatment from others because they have never known anything

more positive.44 There is also the possibility that disabled children may be

schooled into accepting others having access to their bodies.

Child protection enquiries and action planning need to take into account that a

disabled child may be dependent on an abuser for personal care and/or for

communication assistance. They may be less able to tell someone what is going

on because of this dependency. (Source: National working Group on Child

Protection and Disability. It doesn’t happen to disabled children NSPCC 2003, as cited by Gov.uk, July 2009)

9. Communication Barriers

Communication barriers mean that many disabled children including deaf children have difficulty reporting worries, concerns or abuse.

Some disabled children do not have access to the appropriate language to be able to disclose abuse; some will lack access to methods of communication and/or to people who understand their means of communication.

Even if a child can find the confidence and the means to tell about abuse, many of the avenues open to abused children such as telephone help-lines and school based counselling are inaccessible to many disabled children.

There is significant vulnerability for children who use alternative means of communication and who have a limited number of people who they can tell, since these same people may be the abusers.

There is often a lack of access to independent facilitators or people familiar with a child’s communication method.

Research into children’s advocacy services has found that over two fifths of services could not provide advocacy for children and young people who do not communicate verbally and over a third of services could not provide advocacy for children with autism.

Although

there have been some developments in the provision of appropriate vocabulary

in augmented communication systems researchers have found these are not

widely used and that professionals have concerns about the levels of

understanding that disabled children might have about concepts of abuse. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

9.1. Case Study

A child who made an initial disclosure using an augmentative communication system produced the following statement using her symbol board:

‘nurse R cross she tell me up children up she mean cruel hurt leg her hand I cry’

The statement was subsequently repeated by the child in an interview and was clarified through careful questioning to mean:

‘nurse [beginning with] R [got] cross. She tell me [to shut] up, [that I would wake the other] children up. She [is] mean/ cruel she hurt [my] leg [with] her hand I cry’

The child did not have shut, smack or hit on her word board and therefore was

not able to tell her story accurately the first time. (Source: Triangle, as cited by Gov.uk, July 2009)

10. Lack of Participation and Choice

Lack of participation and choice in decision-making can disempower

disabled children and make them more vulnerable to harm as can a failure to

consult with and listen to disabled children about their experiences. Disabled

children may have learnt from their care or wider experience to be compliant

and not to complain. Morris found that disabled children’s privacy was often

not respected nor was there any encouragement to make choices for themselves,

which in turn undermined their opportunities to develop confidence and

self-esteem. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

10.1. Case Study

An eighteen year old young man was denied hospital treatment on the basis that

he was unable to understand the procedure, could not meaningfully consent and

there were concerns about how his behaviour would be managed following the

operation. The young man’s family with the support of an advocate challenged

the decision on behalf of the young man. A symbol and picture communication

book was produced by the advocate, detailing every stage of the operation. This

meant that that the young man could give meaningful consent and understand

what would happen immediately after the operation. A High Court finally ruled

that the operation should go ahead. (Source: The Children’s Society, as cited by Gov.uk, July 2009)

11. Factors associated with disability or health condition

Factors associated with impairments can lead to greater vulnerability to

abuse. Behaviours indicative of abuse such as self-mutilation and repetitive

behaviours may be misconstrued as part of a child’s impairment or health

condition. It is of vital importance that professionals are adequately trained and

alert to recognise indicators of potential abuse or changes in children, which

might indicate that something is wrong, and to understand particular behaviours

associated with impairments. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

11.1. Case study 1

A seven year old boy’s constant masturbation was ‘explained’ by his autism and

his attempts to touch adults sexually were initially attributed to his confusion

about boundaries. Several years later his father was convicted of sexual assault of

all three children in the family. (Source: Triangle, as cited by Gov.uk, July 2009)

11.2. Case study 2

Extensive bruising to the face, chest and arms of an eleven-year-old girl was said

to result from falls during epileptic seizures. Medical advice was that the bruising

was incompatible with falling and child protection procedures were initiated.

(Source: Department of Health (2000) Assessing children in need and their families:

practice guidance, as cited by gov.uk, July 2009)

12. Isolation

Isolation from other children and adults means that many disabled

children struggle to tell others about their experiences making it easier for abuse

and neglect to remain hidden. Having few contacts outside the home, and

inadequate and poorly co-ordinated support services for both disabled children

and their families can increase isolation. The National Working Group on Child

Protection and Disability note that disabled children (and others close to them)

may not communicate about abuse because of a fear of losing the services on

which they depend (NSPCC, 2003, as cited by Gov.uk, July 2009).

12.1. Case Study

A seventeen year old girl was visited at different times of the day and on different

days of the week by her advocate. On each occasion the girl was found in a

sparse day room sitting alone with a pile of Lego bricks on a tray in front of her.

When challenged about this the staff showed the advocate an activity timetable.

However there remained no evidence of any other activity taking place, no

choice for the young women and she was not able to describe any other things

she had done, places she had visited or people who had visited her.

(Source: The Children’s Society, as cited by gov.uk, July 2009)

13. Double Discrimination

Double discrimination faces many disabled children from black and minority ethnic groups and refugee and asylum seeking children.

They can experience additional difficulties and challenges in accessing and receiving services and often those they do receive are not sensitive to their culture and language or relevant to their needs.

Robert and Harris draw attention to the risk of disabled children from refugee and asylum seeking families being severely isolated and hiding their impairment through fear of being different or of this adversely affecting their immigration status.

Disabled children and young people are particularly vulnerable to forced marriage because they are often reliant on their families for care, they may have communication difficulties and they may have fewer opportunities to tell anyone outside the family about what is happening to them.

Parents may want to find a carer for their child in the future, or are under pressure to follow cultural norms.

Some disabled young people do not have the capacity to consent to marriage.

Some may be unable to consent to

consummate the marriage – sexual intercourse without consent is rape. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

13.1. Case Study 1

Nina was born blind and at the age of 16 she continued to be incontinent and

had no feeling in her fingers or toes. At the time she attended the local school

with support from a classroom assistant who assisted children with visual

impairment. During a one-to-one session, Nina disclosed to the assistant that she

was going to Pakistan to be forced to marry. She explained that she didn’t want

to go or get married and she asked for help. The assistant arranged for the local

police to meet Nina on her way home. Again, she stated that she didn’t want to

get married and she wanted help. The police officer organised for her to be taken

to accommodation for young people with disabilities. Nina stayed in the care of

the local authority for several months and started to have contact with her family

again. Eventually she was persuaded to return home and, despite her earlier

protests, agreed to go to Pakistan with them. The police were later notified that

she died from “food poisoning” and she was buried in Pakistan.

(Source: The Forced Marriage Unit, as cited by Gov.uk, July 2009)

13.2. Case Study 2

A thirteen year old Arabic speaking boy whose parents were from Somalia was

placed in a residential special school. When an advocate visited him for the first

time it became clear that he had no opportunity to practice his Muslim religion

and no effort had been made to meet his cultural dietary needs. His sense of

isolation was acute both from his family and his culture. The advocate

immediately referred the boy for an Arabic speaking independent visitor.

(Source: The Children’s Society, as cited by gov.uk, July 2009)

14. Extended periods away from home

Spending greater periods of time away from home, particularly in residential settings, is a risk factor for abuse and Utting noted that this risk is compounded in the case of disabled children.

Researchers have examined the particular vulnerability of disabled children in residential care linking this to characteristics of institutional life, problems in management and staffing and separation of children from parents and others whom they trust and who are able to understand their communication methods.

The welfare of disabled children at residential schools (especially those with 52 week provision) and in health units has been questioned given the wide variation in practice of notifying the responsible local authority of the child’s placement as required by section 85 of the Children Act 1989.

Researchers concluded that for children in placements funded solely by education there is unlikely to be anybody other than a parent actively checking whether or not the child is safe and happy.

However a third of disabled children living in residential care have been found to be isolated from their parents.

The Second Joint Chief Inspectors Report found that less than 50%

of residential special schools met the National Minimum Standards for

responding to complaints and just 40% of residential special schools did not

meet or only partially met the National Minimum Standards for child protection

systems and processes. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

14.1. Case Study

On a visit to a disabled teenager in residential care an advocate asked to take the

young man out to the local park. He was told that two care staff would have to

accompany him. The young man was strapped by each arm to a member of staff,

the rationale being given that the young man would run away. On further

investigation by the advocate it transpired this practice had been

going on for several years without review. The advocate challenged the approach

and after much perseverance the young man was allowed to visit the park with

his advocate without being strapped to anyone. (Source: The Children’s Society, as cited by gov.uk, July 2009)

15. Lack of training and/or understanding

Lack of understanding and training about safeguarding disabled children can result in professionals not recognising the signs of abuse or neglect.

This is all the more worrying given that research indicates that the identification of the abuse of disabled children is most likely to come from observations of physical signs, behaviour or mood changes.

Researchers found the coverage of safeguarding during the induction of residential school staff was poor or non-existent, and staff in residential special schools sometimes missed out on opportunities to participate in multi agency training.

Practitioners in child protection teams may have no specialised knowledge of disability, whilst disability specialists may have limited knowledge of child protection.

Cooke and Standen in their study of four local authorities highlighted that during the course of a year the names of disabled children were less likely to be put on the child protection register than a comparison group of non-disabled children.

Partnerships between providers and PCTs are essential to ensure care for

disabled children with complex health needs is provided safely. As more short

break services are commissioned it is essential that sufficient staff are trained to

ensure they are competent to deliver safe care in areas such as ventilation and

tube feeding. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

16. The Criminal Justice System

Practices within The Criminal Justice System can create barriers during child protection investigations relating to disabled children.

In the past the Safeguarding disabled children: practice guidance evidence of disabled children was rarely given in court because those involved in investigating allegations often assumed that disabled children would not be able to give credible evidence in criminal proceedings.

However, research clearly indicates that children with learning disabilities can provide forensically relevant information if appropriate methods are employed.

The pilots and now the

introduction of intermediaries under The Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act

1999 are intended to ensure that everyone, including children with learning

disabilities can give their best evidence in a criminal court. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

16.1. Case Study 1

The foster parent of a thirteen year old boy with autistic spectrum disorder

noticed on a visit home from residential school, bruising to his body and a black

eye and on another occasion a fractured hand. The school had no record of any

injuries and there was no explanation provided about how he had sustained

them. His foster parent believed he could have indicated how he had been hurt.

However because the child was not able to communicate verbally, a witness

statement was not taken. (Source: National Working Group on Child Protection

and Disability. It doesn’t happen to disabled children. NSPCC, 2003, as cited by gov.uk, July 2009)

16.2. Case Study 2

A fifteen year old boy in a residential placement was hit by a member of staff and

disclosed this to another staff member. The Local Authority, the police and the

boy’s advocate were contacted and the staff member concerned removed while

the investigation took place. The advocate and staff at the home advised the

Police about the young man’s method of communication and the advance

preparation that would be needed. The advocate was asked to accompany the

young man to the interview. It immediately became clear no preparation had

been done and the interview was not conducted in a child focused manner. As a

result the Police were unable to obtain a full account of the incident from the

young person. The advocate gave feedback to the police about the inappropriate

way the interview had been conducted. The case was eventually dropped.

(Source: The Children’s Society, as cited by gov.uk, July 2009)

17. Limited education

Limited personal safety programmes and personal, social and sex

education for disabled young people results in them being less aware about

abusive behaviour and less able to communicate about abuse. Oosterhoon and

Kendrick reported on the challenges for teaching staff of teaching abstract

concepts of sexuality, sex education and abuse. Some awareness raising and

keeping children safe materials are built on assumptions about a child’s abilities

such as ‘Say no, go run and tell’ and could be counterproductive for disabled

children. Some children’s dependence upon others for intimate care requires the

education to be tailored to meet the needs of the child and a focus, on for

example appropriate and inappropriate touching. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

18. Higher levels of bullying

Higher levels of bullying of disabled children have been found in a number of recent studies and in some instances the severity of bullying or harassment of disabled children could be classified as assault or abuse.

The experience or anticipation of being bullied can shape a young person’s sense of self and social relationships and can have a corrosive and damaging impact on their self-esteem, mental health, social skills and progress at school.

For some disabled children bullying can be an insidious and relentless pressure that can dominate their lives, leaving them feeling depressed and withdrawn.

The lack of self esteem resulting from bullying can create can in itself make disabled children more vulnerable to abuse. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

18.1. Case Study

A twelve year old girl with learning disabilities was being physically bullied for

over three months before any action was taken, despite telling parents and

teachers at the start. ‘He would push and swear at me, say mean things and walk

up and slap me’. (Source: National Childrens Bureau, Bullying and Disability

Spotlight Briefing 2007, as cited by gov.uk, July 2009)

19. DBS checks and suitability of carers

*Please note: The information below was written in 2009 and CRB has now changed to DBS.

Greater use of direct payments and personal budgets, whilst supporting empowerment and choice, does carry some risks of children being harmed if the minimum requirements in respect of checks and references on those providing personal care have not been followed up.

The Direct Payments guidance Community Care, Services for Carers and Childrens Services (Direct Payments) Guidance, England (2003) makes it clear that the system of direct payments should not place a child in a situation where they are at risk from harm.

The local authority can exercise their discretion and refuse to give a direct payment if they consider a child is being placed in a situation where they would be at risk of harm as a result by being cared for by an unsuitable person.

However the local authority cannot insist that the person employed through Direct Payments should have a Criminal Record Bureau (CRB) check, prior to their employment (or be registered with the Independent Safeguarding Authority, when legislation, under the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006 comes into force) although of course this is strongly advised.

Requesting a CRB check, together with the taking up of references, whilst not guaranteeing that a person is suitable to work with children, does offer a degree of reassurance about a carer's suitability to undertake such work.

In situations where the family decides not to accept the local authority’s advice about best safeguarding practice some local authorities are asking the family to sign a statement stating that the issue has been discussed with them and they are aware of the risks involved . Such statements do not of course absolve the local authority of their duties to safeguard the welfare of children. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

20. Resources

The following pages contain some useful resources for you.

20.1. Legislation

Below is a list of relevant legislation. The name of each piece of legislation is a clickable link to the legislation and will open in a new window. Please note you do not need to read every piece of legislation. They are here for future reference should you need to refer to them.

The Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1995

Disability Discrimination Act 2005

Duty to Promote Disability Equality Statutory Code of Practice

The Children Act 1989 Guidance and Regulations, Volume 6 Children with Disabilities

The Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families

Carers and Disabled Children Act 2000

Health and Social Care Act 2001

Adoption and Children Act 2002

The Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006

20.2. Frameworks and Policy Developments

Frameworks and Policy Developments Every Child Matters: Change for Children (2003) (http://www.everychildmatters.gov.uk/publications/) sets out the government’s aim for every child, whatever their background or their circumstances to have the support they need to

- Be healthy

- Stay safe

- Enjoy and achieve

- Make a positive contribution

- Achieve economic wellbeing

Every Child Matters aims to integrate services for children aged from 0 to 19 with agencies working together across professional boundaries to co-ordinate support around the needs of children and young people.

Children's Trusts bring

together all services for children and young people in an area, underpinned by

the Children Act 2004 (http://www.opsi.gov.uk/Acts/acts2004/

ukpga_20040031_en_1) duty to cooperate and to focus on improving outcomes

for all children and young people.

The Children Plan (2007) (http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/childrensplan/) is the government’s vision of how it intends to improve children and young people’s lives over the next 13 years to 2020. It includes making a reality of the government’s aspiration to make safeguarding children everyone’s responsibility. The plan made a commitment to strengthen the way in which complaints about bullying are dealt with and to consider how to address bullying that takes place outside school.

The Children Plan One Year On (2008) (http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/childrensplan/) updates on progress and the proposed actions to prevent and tackle bullying including requiring schools to record all incidents of bullying.

The National Service Framework (NSF) for Children, Young People and

Maternity Services (2004)

(http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/NationalServiceFrameworks/Children/

DH_4089111) requires all agencies to work to prevent children suffering harm

and to promote their welfare, provide them with the services they require to

address their identified needs and safeguard children who are being or who are

likely to be harmed. Standard 8 of the NSF focuses on disabled children and

notes that disabled children are more likely to experience abuse than non-disabled children and that children living away from home are particularly

vulnerable. Standard 8 requires that Local Authorities, PCTs and NHS Trusts ensure

that LSCBs have a system in place to ensure that all disabled children are

safeguarded from emotional, physical and sexual abuse and neglect. The NSF

requires interagency safeguarding children protocols to be comprehensive and

notes that for disabled children this means:

- Safeguarding protocols include agreement in relation to:

- Consulting with disabled children, and organisations advocating on their behalf, about how best to safeguard them;

- The development of emergency placement services for disabled children who are moved from abusive situations;

- The systematic collection and analysis of data on disabled children subject to child protection processes;

- Safeguarding guidance and procedures for professional staff working with disabled children;

- Training for all staff to enable them to respond appropriately to signs and symptoms of abuse or neglect in disabled children;

- Guidance on contributing to assessment, planning and intervention and child protection conferences and reviews;

- Disability equality training for managers and staff involved in safeguarding children work; and

- Regular reviews and updating of all policies and procedures relating to disabled children.

The Children and Young Persons Act 2008

(http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2008/ukpga_20080023_en_1) places a new duty

on local authorities to provide short breaks services for disabled children and

their families. The Act makes clear that breaks should not just be provided to

those carers struggling to maintain their caring role, but also to those for whom a

break would improve the quality of the care they can offer. The new duty is

intended to come into force in April 2011. (Gov.uk, July 2009)

20.3. Websites

Websites containing information about resources to support communication with disabled children including:

www.everychildmatters.gov.uk/socialcare/ integratedchildrenssystem/resources/ contains information about resources to help with enabling children to be involved in decision- making, advice and information about involving disabled children and resources to help practitioners communicate with disabled children.

www.disabilitytoolkit.org.uk designed by practitioners at The Children’s Society, the is a one-stop information hub, providing essential resources, information and support that are required by professionals to support disabled children in decision-making and participation activities. This website is fully interactive and encourages users to share their resources, practice and ideas using the upload facility. Currently the database contains information on 45 resources reviewed by practitioners and 17 examples of good practice.

www.ace-centre.org.uk provides support and advice in relation to children and young people with complex physical and communication impairments. The website offers information about assessments, communication technology and other methods of communication and the training available for the people supporting children to communicate.

www.talkingpoint.org.uk I CAN runs a website called Talking Point. This provides a wide range of information about speech, language and communication. The site is for parents and professionals who help children with speech, language and communication needs and includes speech and language information, a glossary, a directory of resources, news, case studies, discussion groups, ask-the-panels write ups and frequently asked questions.

www.callcentre.education.ed.ac.uk/ provides a wide range of information guidance and resources on how Information Technology can assist disabled children including many free resources about Augmentative and Alternative Communication.

http://hbr.nya.org.uk/ The Hear by Right website provides ready access to a

range of resources aimed at improving participation for all young people. Many

of these resources can be used with no little or no adaptation for disabled

children and young people depending on the nature of their impairment. Of

particular interest is the standards framework, which has been used to assess the

quality of young people’s participation across the range of statutory and

voluntary organisations.

The Speech Language and Communication Framework developed by

The Communication Trust is a comprehensive framework of speech, language

and communication skills and knowledge needed by anyone who works with

children and young people. It is available to download and can be used as an

interactive online tool at www.communicationhelppoint.org.uk. Practitioners and

managers can complete an on line evaluation of current skills and knowledge

and identify competencies. The website links to training and resources that will

support these competencies.

(Gov.uk, July 2009)

20.4. Communication Resources

A Lot to Say written by Jenny Morris and published by SCOPE is a guide for social workers, personal advisors and others working with disabled children and young people with communication impairments. Available to download from www.scope.org.uk/downloads/action/publications/lotsay.pdf

How it is consists of an image vocabulary for children about feelings, rights and safety, personal care and sexuality. The vocabulary comprises 380 images that are designed to be used as a flexible resource to support children to communicate about their feelings, bodies, rights and basic needs. The pack includes a booklet and CD ROM. More information is available from www.howitis.org.uk Available to purchase from: NSPCC Publications and Information Unit, NSPCC, 42 Curtain Road, London EC2A 3NH. Tel: 020 7825 2775. Email infounit@nspcc.org.uk.

How to use easy words and pictures produced by the Disability Rights Commission is an Easy Read guide that describes what Easy Read is and why it is needed and used. There is useful advice about how using the right words and pictures makes information easier to understand. Available to download from http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/publicationsandresources/Pages/ HowtouseEasyWordsandPictures.aspx

How to involve children and young people with communication impairments in decision-making is one of the series of ‘How to’ guides from Participation Works. It covers what is meant by communication impairment, barriers to communication, creating the right culture, accessible information, getting to know children and young people, practical suggestions and additional resources. Available to download from: www.participationworks.org.uk

I’ll Go First newly updated planning and review toolkit designed by with and for disabled children to enable them to communicate their wishes and feelings. The pack includes a series of colourful, hardwearing boards for children to complete with illustrations and electrostatic stickers and topics including keeping safe, review meetings and healthy living. A CD ROM version with a range of drag and drop objects, activities, people and feelings allows children to create their own online record of their views, wishes and feelings. Available to purchase from: The Children’s Society PACT Project Tel: 01904639056 or email: pact-yorkshire@childrenssociety.org.uk

In My Shoes is a computer package that helps children and adults with learning disabilities communicate their views, wishes and feelings as well as potentially distressing experiences. It has been used in a wide range of circumstances, including with children who may have been abused and has been used successfully in interviewing vulnerable adults. Further information from http://www.inmyshoes.org.uk/index.html

Listen Up produced by Mencap, is a toolkit of multi-media resources to help children and young people with a learning disability complain about the services they use. Available free from Mencap publications, 123 Golden Lane London EC1Y 0RT Tel: 020 7454 0454.

My Life, My Decisions, My Choice is a set of resources to aid and facilitate decision-making including a poster, set of laminated ring bound cards and a guide for professionals. The resources, produced by The Children’s Society were designed with disabled young people and are aimed at young people, and the professionals that work with them. Available free to download from: http://sites.childrenssociety.org.uk/disabilitytoolkit/about/resources.aspx or in hard copy format from The Disability Advocacy Project Telephone 020 7613 2886.

Personal Communication Passports are a resource outlining the key principles of making and using communication passports as a way of documenting and presenting information about disabled children and young people who cannot easily speak for themselves. Available from www.callcentre.education.ed.ac.uk/ where the resources can be explored online before purchasing. Tel: 0131 651 6236. A website to specifically address questions about planning, creating and using passports can be accessed at www.communicationpassports.org.uk

Talking Mats is a low tech communication framework involving sets of symbols. It is now an established communication tool, which uses a mat with pictures/ symbols attached as the basis for communication. It is designed to help people with communication difficulties to think about issues discussed with them, and provide them with a way to effectively express their opinions. Talking Mats can help people arrive at a decision by providing a structure where information is presented in small chunks supported by symbols. It gives people time and space to think about information, work out what it means and say what they feel in a visual way that can be easily recorded. Available from Talking Mats Telephone 01786 467645 Email info@talkingmats. More information http://www.talkingmats.com/ Ten Top Tips for Participation

What disabled young people want. This poster is written in words used by young people and gives advice about how to ensure disabled children and young people have a say in decisions, which affect their lives. Available as free download from: http://www.ncb.org.uk/Page.asp?originx_666ui_67604737284116e48a_200835330g

Two Way Street: Communicating with Disabled Children and Young People is a

training video and handbook about communicating with disabled children and

young people. The video is aimed at all professionals whose role includes

communicating with children and was developed in consultation with disabled

children and young people. The handbook (also available separately) gives

further information and guidance plus details of the main communication

systems in current use in the UK and annotated references to good practice

publications. Available to purchase from: www.triangle-services.co.uk

Tel: 01273413141. More information available from

http://www.triangle-services.co.uk/index.php?page=publications

(Gov.uk, July 2009)

20.5. Safeguarding Resources

Advice and information lines focused on safeguarding of disabled children and services supporting disabled children who are victims of abuse

Ann Craft Trust offers advice on issues relating to the protection of vulnerable children and adults. Provides advice for professionals, parents, carers and other family members on general issues and specific cases. Contact 0115 951 5400 or for more information http://www.anncrafttrust.org/Advice.html

NSPCC Child Protection BSL Helpline for deaf or hard of hearing people who are worried about a child or need advice provides access to high quality BSL interpreters within minutes. Contact via ISDN videophone on 02084631148 or online via IP videophone or web cam to nspcc.signvideo.tv

Respond provide a telephone helpline for young people and adults with learning disabilities who are being abused or who are worried about abuse. The service is also available for parents, carers and professionals. Contact the free help line number 0808 808 0700

Triangle provide consultancy working alongside those conducting child

protection investigations, including ‘facilitated interviews’ and supporting the

prevention and investigation of institutional abuse and the development of safer

practice. Contact: Triangle www.triangle-services.co.uk Tel: 01273413141

Voice UK gives support, information and advice for disabled young victims and

witnesses of crime and abuse, their families and carers and professionals. Contact

the free help line number 0845 122 8695 or email helpline@voiceuk.org.uk

(Gov.uk, July 2009)

22. How does a child with a disability communicate that they are being abused?

How does a child with a disability communicate that they are being abused?

Well, they may not communicate this to you, or anyone else. They may not understand that they are being abused or they may not have the vocabulary to convey this message. This is when you should be aware of the signs of abuse and report any concerns that you may have immediately to your line manager or designated safeguarding lead.

A child with a disability may be able to verbally communicate with you that they are being abused. however, there may be children who are unable to do this. They may have other communication methods, some of which are globally recognised. The children and young people that you work with may use Makaton, sign language, communication aids, gestures and body language to name but a few.

Finally, a child or young person may display behavioural changes due to distress or anxiety stemming from the abuse that they are victim too. Whilst behavioural changes may occur for many reasons it is important that you are aware of this factor and report your concerns immediately.

22.2. Communication Considerations

As we've mentioned, children with disabilities may have limited communication or lack of access to an appropriate vocabulary. This may make it difficult for them to tell others what is happening.

It is also important to recognise that communication systems may lack the language or terminology necessary to enable the child to disclose abuse.

Active steps are therefore needed to remove barriers and promote communication. This means including other people who are familiar with a child's individual communication methods – for example, teaching assistants, parents, and carers.

(Blackpool Council, 2024c)23. Impeding the safeguarding of children with disabilities

Over-identifying with the parent or carer. This can lead to reluctance in accepting that abuse or neglect is taking place, or seeing it as being attributable to the stress of caring for a disabled child.

A lack of understanding about the impact of a disability on a child, or health conditions that may present as signs of possible abuse – for example, fragile bones.

- A lack of knowledge about what is 'normal' or usual behaviour for that particular child

- Not understanding a child's method of communication

- Confusing or making assumptions about behaviours that indicate a child may be being abused with those behaviours associated with the child's disability or impairment

- Failing to identify a child's behaviour that indicates stress; sexually harmful or self-injury can be indicative of abuse.

(Blackpool Council, 2024c)

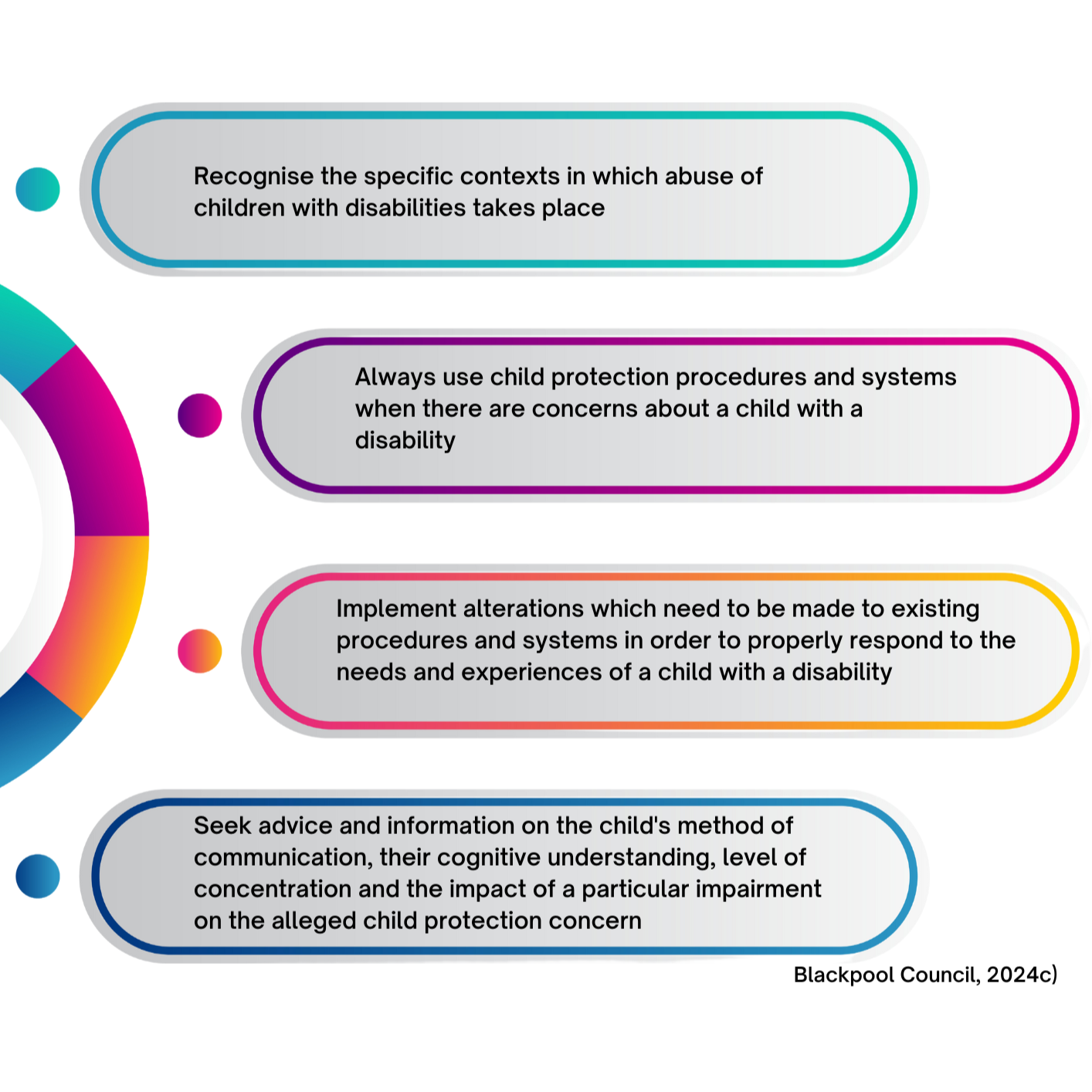

24. Protecting Children with disabilities

Protecting children with disabilities

25. Case Study and Activity

Case Study by Caroline EcclestonPlease complete the multiple choice question available here.

26. Considerations during an investigation

According to Blackpool Council (2024c) these are the things that should be considered during an investigation:- Children with disabilities should be treated with the same degree of professional concern afforded to non-disabled children.

- Social workers must be prepared to challenge carers and ensure that abusive and restrictive practices do not go unrecognised and are addressed and changes made. Any impairment should not detract from early multi-agency assessments of need that consider possible underlying causes for concern.

- You may need to allow extra time to conduct the investigation of potential or alleged abuse or neglect.

- All assessments must have up-to-date information about the child’s needs and care they are receiving. A disabled child may have been supported by a number of agencies, and information will need to be collected from all of these.

- The child’s voice must be evidenced throughout the assessment. You may need to find creative ways to help the child express their views, wishes and feelings.

27. Identifying the perpetrator

A child with a disability may be in contact with many people so if the perpetrator is not known, it may be much harder to identify them. Within any risk management plan it is essential to consider everyone providing care to the child. Whilst the investigation is ongoing and the perpetrator of the abuse has not been identified, it may be that alternative carers are sought. (Blackpool Council, 2024)

How many different people can you think of that may have contact with a child with disabilities?

There may be:

- Foster carers

- Parents

- Family members

- Support workers

- Social workers

- Respite staff

- Care workers

- Therapists

- Education staff

- Escorts

- Drivers

- and all the other people the child is in contact with

28. Disclosing Abuse

If a child with disabilities is dependent on an abuser, it may not be safe for the child to disclose abuse. This should be taken into account during an investigation. Disclosure may be impossible for the following reasons:

- If the child depends on the carer for personal care, essential treatment, medication or communication assistance etc

- If the child has a professional or personal relationship with the abuser

- If the carer is in a position of power over the child or in delivering the care package

If disclosure is seen as essential before action can be taken, this in itself can put the child at risk. Different investigative methods may need to be pursued, and possibly greater reliance placed on other evidence to inform risk assessment and the balance of probability of abuse taking place. (Blackpool Council, 2024c)

29. The impact of failures in an investigation

If appropriate investigations are not carried out thoroughly, opportunities to protect children with disabilities are lost.Failure to conduct investigations in accordance with Local Safeguarding Children Board (LSCB) policies will mean that cases may not be taken to the Initial Child Protection Conference in a timely manner. This will contribute to placing the child at further risk.

If an Initial Child Protection Conference is not convened there will be:

- No multi-agency analysis of the investigations

- No forum for multi-disciplinary consideration of risk

- No statutory process for ongoing monitoring of concerns

The particular vulnerability of children with disabilities means that, even if a decision is taken not to make the child subject to a Child Protection Plan, other action may need to be taken to address concerns, such as supporting the family through a robust Child in Need plan.

A Child Protection Conference offers the opportunity for a multi-agency response and a system for reviewing action taken to protect the child.

Good assessments support professionals to understand whether a child has needs relating to their care or a disability and/or is suffering, or likely to suffer, significant harm.

The specific needs of disabled children and young carers should be given sufficient recognition and priority in the assessment process.

Further guidance can be accessed at 'Safeguarding disabled children: Practice guidance, 2009' and 'Recognised, valued and supported: Next steps for the Carers Strategy, 2010'.

All information on this page is from Blackpool Council (2024c)

30. Additional Issues to consider

Information from Blackpool Council (2024c)31. Next steps

According to Blackpool Council (2024c) 'once the assessment is completed, the social work team manager in consultation with the social worker will decide whether the case should be managed as a Section 17 Child in Need investigation, or whether a Section 47 investigation is required.'