OER 1 Attitudes to languages and gender

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | English Medium Education and Gender Equality (EMEGen) Open Educational Resources |

| Book: | OER 1 Attitudes to languages and gender |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 23 November 2025, 9:14 AM |

Description

1 Languages, gender, status and marginalisation

When a language is seen to have high status and importance, access to it can be limited for learners who are marginalised, and learners who have restricted opportunities or roles in society.

These learners may be:

- girls and women

- learners from minority ethnic communities

- learners from language minority groups

- learners living in poverty

- learners who have experienced forced migration.

Social and cultural contexts affect how we experience languages and language learning. Social and cultural expectations influence what we do with our languages. The value of a language will vary for individuals and groups, depending on how and why they use the language, and how they are expected to use the language by others.

Attitudes to languages are influenced by what teachers, families, girls and boys see as the status and purposes of the languages and interactions of language, gender, status and marginalisation can be noticeable where English is the medium of school instruction.

Think of examples from your own experience:

- Are some languages in your context more important than others?

- Are there languages that are considered to be more important for men, and languages that are considered more important for women?

- In your context, why do some students learn English, but not others?

- Are there different expectations for girls and boys, or for certain groups of students, when it comes to learning and using English?

- What do learners in your context hope to do with their languages?

With these ideas in mind, now read from the EMEGen research.

2 EMEGen research

English is considered to be more prestigious and demanding than local language education, and sometimes English is more expensive than local language education.

English is associated with higher levels of study, travel abroad for study or work and professional employment, as this parent and student from different parts of the world explain:

Whatever one wants to be, engineer or doctor, they need English.

(Parent of male student, Nepal)

English will help me in my university education because that is the language used for teaching and communication in the university.

(Male student, Nigeria)

National and local languages are considered to be more appropriate for learners who are expected to work in or near the home, not continue to further education, or not travel out of the community.

National and local languages are seen as more valuable for learners who are expected to take government or community jobs, or to become homemakers, as this district official and parent note:

Many girls want to do well in public service commission examinations, and they will need [our national language] or that purpose.

(Policymaker in Nepal)

The role of education for my son’s and daughter’s future can be different; because for my daughter, her education is going to be useful to her after her marriage […] She can take care of her children and husband properly.

(Parent in Nigeria)

Home languages are also significant in feelings of identity, connection and belonging, cultural knowledge, and participation in family and communal life – areas which can be seen as the responsibility of girls and women:

In the Hausa-medium school the child will learn about her culture and give importance to it. She will also learn a lot about her language, unlike in an English-medium school.

(Parent of female student in Hausa Medium school, Nigeria)

[My] mother tongue helps to express feeling with my mother and other relatives.

(Female student, English Medium school, Nepal)

Note: All quotes are taken from interview data generated in the EMEGen research in Nigeria, where Hausa is the language of instruction in Hausa medium schools, and in Nepal, where Nepali is the language of instruction in Nepali medium schools.

English can perpetuate inequalities in strongly gendered societies, where girls are not encouraged to continue in education, achieve well, or pursue higher education and careers. Where English medium schools are fee-paying and better-resourced, boys are over-represented.

Where girls study local languages and boys study English, some employment sectors become gender and language segregated. English can also be a barrier to learning for linguistic minority students, who must use a national or local language plus English as second and third languages for learning.

Learning and using English can exclude girls and boys from marginalised communities who may face barriers to education, or to certain jobs or roles in society.

With the EMEGen research in mind, now go to your activities.

3 Activities for school leaders

In these activities, you will audit and celebrate the languages of your school, and consider how prepared students are to learn in the language of instruction. You will also informally observe how teachers and students work within the language rules or policy of the school.

3.1 School leaders – Activity 1

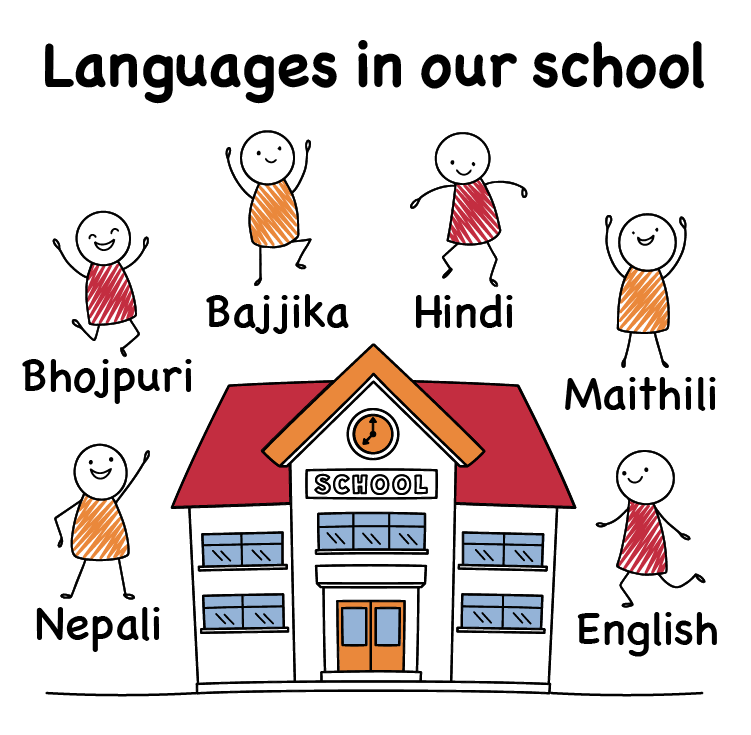

Audit and celebrate languages in your school

Audit and celebrate languages in your school

1. Make an informal audit of languages in your school.

b. What languages do students have?

c. You can sketch this out as a diagram or a chart, noting:

i. majority languages

ii. minority languages dialects

iii. other ‘foreign’ languages that teachers and students use such as French, Arabic or English.

2. Do teachers and students have languages in common?

3. Based on the information you gather, create a simple display of all the languages of the school. You can ask students to help.

Such displays celebrate all the language resources of your teachers and students.

You can value and celebrate all languages, even if teachers and students are required to use one language in the classroom. When you have knowledge of the languages your staff and students use, you can think about different forms of support that students and teachers might need. You can also consider how these languages can be resources for teaching and learning. For instance, can students of the same language backgrounds work together? Can teachers who have a local language support groups of students to improve?

Reflection: how prepared are students and teachers?

In many countries around the world, the language policy allows or directs teachers to use a local language in the early years of schooling. This transitions to English or one of the national languages in upper primary school. In secondary school, it is usually one language only – English or a national language.

- In your context, when does this transition happen for your students? Is it gradual or sudden?

- What resources or training are available to support the transition, for teachers and for students?

- How prepared are your students to learn in the language of instruction?

- How prepared are your teachers to support students at different stages of language learning?

- In your context, what additional language support would be helpful to students and teachers?

3.2 School leaders – Activity 2

Observe language and participation

Observe language and participation

1. First, briefly review the language policy or rules for your school.

- What do the rules say about the language or languages that are to be used for teaching and learning? How strict or flexible is this?

- Are the rules the same for teachers and for students?

- Are there any allowances, such as for students from other language groups?

- Is there an official government language-in-education policy that is relevant to your context?

- How is the language policy or rule made known to students and to parents?

2. Make time to walk around your school to listen in on teaching and learning with a focus on languages in the classrooms. You can do this just by standing or sitting outside classes. Such informal, in-the-moment observations can give realistic and useful information and should not put the teacher under pressure. Do this over a few days.

These are not formal observations or assessments of teachers.

The aim here is not to check or enforce the language rules. The goal is to support teachers and students to work as well as possible within the rules.

- Listen to how teachers and students use languages. Do they use one language only, or do they use more than one language? Who does most of the speaking?

- Do teachers use certain languages for classroom management, or for certain subjects?

- If teachers switch between different languages, do students seem to find this helpful?

- If teachers use one language only, do you think this is helpful to all students? Do you think there are differences for girls and boys, or for specific groups of girls and boys together?

- Are students allowed to use local languages outside the classroom, for instance, in break times?

- Are students punished for using certain languages?

- Make notes on what you find.

3. In your observation, do you think any students are left out because of language differences or language abilities?

4. Could you describe these students as a group, if they have things in common such as their language, ethnicity, religion or caste?

5. What could have made a difference to their learning?

6. Write a summary that describes your observations and your thoughts. You can do this in your own notebook, or in the free writing space here.

7. In a staff meeting, without naming any staff or students, share your observations and thoughts with teachers.

Acknowledge to teachers the challenges that they face.

8. Depending on what is permitted in your context, see OER2 for ideas on how to improve student participation and support teachers to try out these activities.

Did you know?

There is research evidence around the world that students’ other languages can help them to learn the language of instruction, not hinder it. See the ‘Further resources’ section for reading on this.

4 Activities for teachers

In these classroom activities you will ask students to explain the languages they use when, where and why. You will also organise students to discuss and debate the purposes of different languages.

These activities aim to:

- develop students’ appreciation of their languages

- encourage students to identify and consider the purposes of different languages in their lives

- enable students to practise language learning.

These activities are also opportunities for you to observe students’ language learning.

You can build on these activities, repeat them with variations for different subjects, adapt them, and share them with other teachers.

Section 5 ‘Activities for informal learning facilitators’ can also be adapted for your classroom.

4.1 Teachers – Activity 1

Class discussion about languages

Class discussion about languages

1. Begin a class discussion about when, where and why we use different languages.

Ask students to give examples of the languages they read, write, hear and speak in different places with different people or groups, and why.

Do we use only one language in these places, or do we mix languages?

- At home

- In school

- In the community

- In the church, mosque or temple

- On the radio/television

- On the internet

- On social media

- On a mobile phone

- In different classes in school, such as Science or History class.

2. Ask students to give examples of the languages they use when we interact with:

- a grandparent

- an elder

- a tourist

- the school principal

- a police officer

- a shopkeeper

- a friend

- on social media

- in an email

- in a messaging app.

Where do we use more or less formal language? Where do we use only one language, and where do we mix languages?

Do we use only words, or do we use images (such as emoticons 😊) or gestures in some situations?

3. Allow students to develop their ideas in the languages they are most confident with – if this is permitted in your school. They can do this with a partner, or in a small group. Then have them practise their ideas in English. They can make notes in English to help them respond.

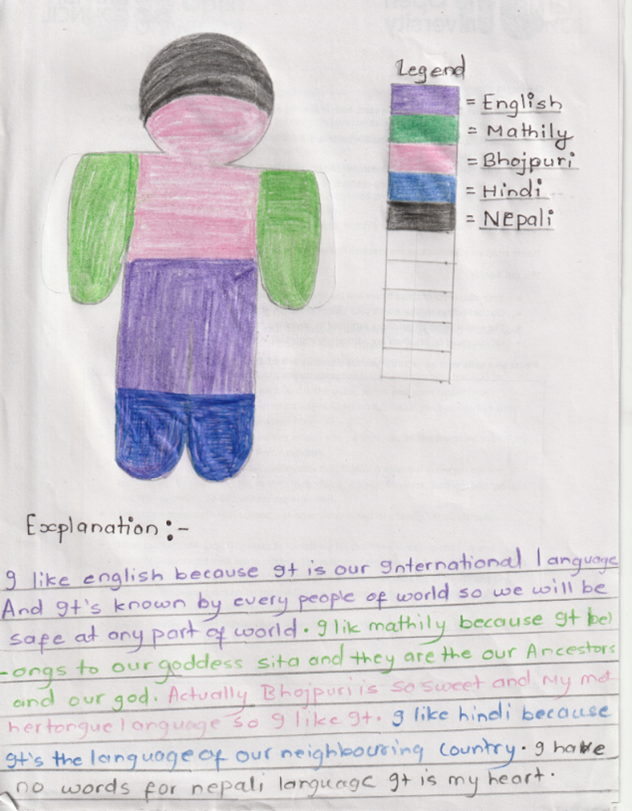

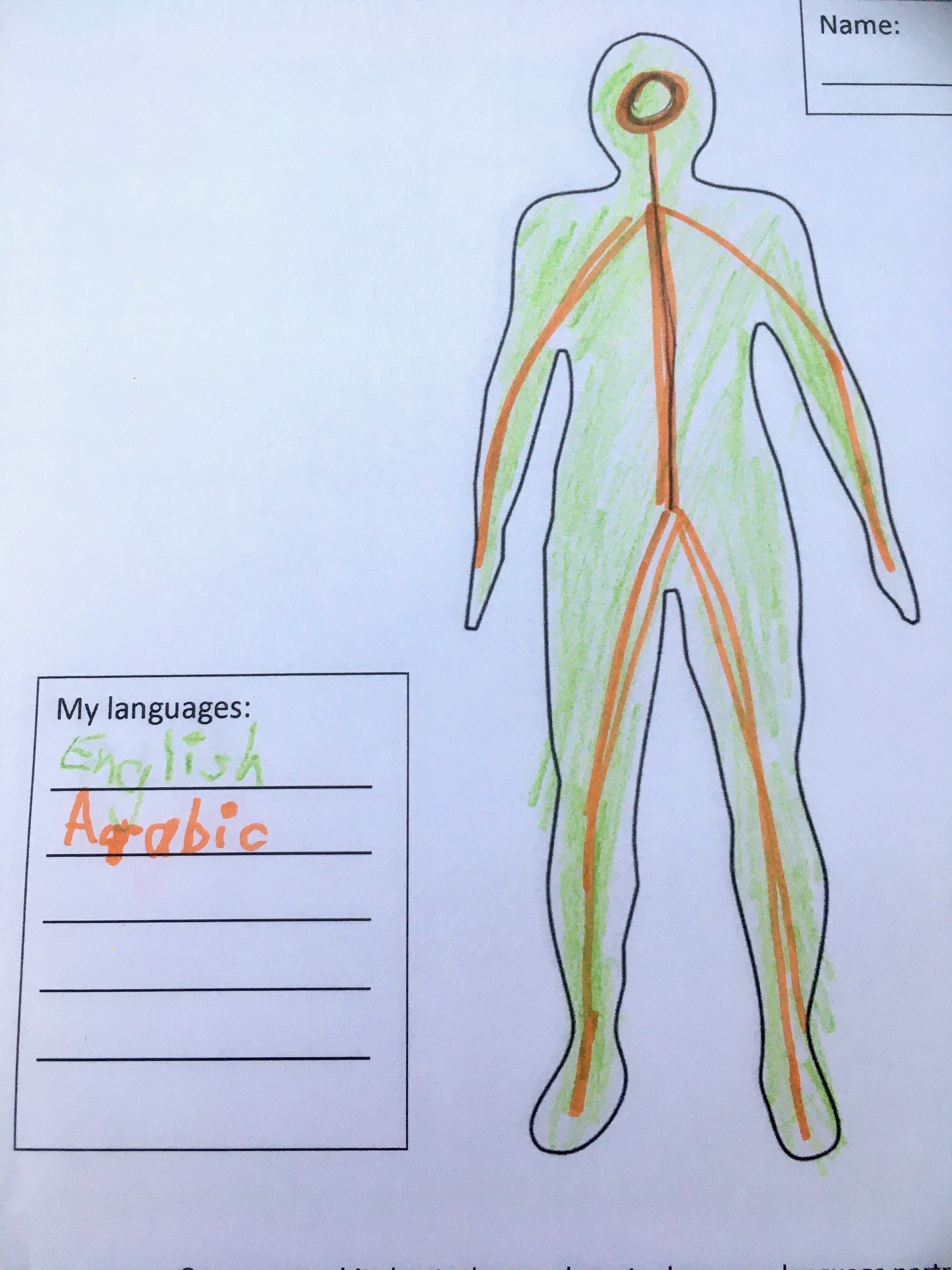

Pictures can prompt discussions about which languages are used for which purposes:

Variation: You can do this activity in a language lesson

Have students talk, write and draw about their languages, to create a ‘language portrait’ of themselves.

You can model pronunciation, vocabulary, phrases and structures, such as:

- ‘When I am at home I use [language] with my grandmother because….’

- ‘I use [language] on the train when it is necessary to….’

Variation: You can do this activity in a subject lesson

Focus the discussion on a relevant topic and the languages students use for it in different contexts. For example, where, how, why and with whom do we talk about numbers, history, science, or technology? Do we use different languages for certain ideas or vocabulary?

Have students discuss with a partner, or in a small group, or make notes, before they present their ideas.

This discussion can help students learn subject content and subject language at the same time.

4.2 Teachers – Activity 2

Languages and purposes

Languages and purposes

In these activities, you have options to plan and try out classroom tasks for students centred around the usefulness and purposes of different languages, with variations for pair work and class debate.

Read through the activities first and then plan a lesson.

The languages can be:

- A national language

- A local language

- English or other foreign languages such as German, French, or Arabic.

Why learn a language?

1. Are some more useful or important than others – why or why not?

2. In the EMEGen research, ‘English’ was often associated with ‘being educated’. What do you think? Why or why not?

3. Have students discuss this in pairs and then give their ideas for you to write on the board. You can create categories of reasons to learn a language, for example:

| Learning/thinking reasons | Social/personal reasons | Career reasons | Learn about the world |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Improve mental quickness Improve vocabulary Be smarter |

Increase confidence Make friends Better listening and understanding Interact with international visitors/tourists |

Increase job prospects Earn more money Get work in another country Serve my country Have interesting work |

Discover new customs and cultures Travel |

Variation: Language lesson activity

You can have this discussion in a language lesson.

Model questions, vocabulary, sentences and phrases orally and on the board, such as:

- ‘I enjoy / dislike [language] because…’

- ‘[Language] is important to learn because…’

- ‘As an adult I will need to know [language] in order to …’

- ‘I will / will not continue to learn [language] because…’

- ‘For me [language] is very useful because….’

- ‘English is not/is the same as being educated because…

‘My parents want me to learn [language] because…’

Variation: Subject lesson activity

You can have this discussion in a subject lesson.

- Are certain languages important to certain school subjects?

- Are certain languages important to certain careers?

Have students discuss the value of different languages to careers linked to the subject. For example, which languages are important to a career in science, engineering, technology, medicine, or journalism?

Have students say why, for example:

- ‘I will need [language] in my career as a [scientist, journalist, accountant…] because….’

Variation: Pair work

1. Organise pairs of students to talk to each other – single-sex pairs or girl–boy pairs, depending on your context.

2. Have pairs ask and answer each other the questions generated from the class discussion. Write vocabulary, sentences, phrases on the board to support students.

3. If it is permitted in your context, allow students to develop their ideas in the language they are most confident with, before having them interact or report back in English. For instance, they can make notes in a familiar language, and then practice orally in English.

Have each pair describe their partner’s ideas.

You can circulate and listen, encourage and offer suggestions, make corrections, and informally assess students’ participation, vocabulary and pronunciation, and their understanding of the topic.

Extension: Class debate

Building on the class discussion and pair work, you can organise a class debate about languages for different purposes, careers, academic ambitions or community life.

1. Have girls v boys, or mixed groups, depending on your context.

2. Allow students to use drawings, photos or pictures to support their points.

3. Allow time for students to prepare, practice and be ready.

4. During the debate, notice the participation of different groups of students.

5 Activities for informal learning facilitators

These activities aim to help learners develop confidence to value and use all their languages for learning.

In these activities, you will support learners to create personal language portraits. You will also support learners to discuss their goals and the languages they need to achieve these goals.

The activities are opportunities for learners to interact, speak and listen with each other.

Activities for teachers can be adapted for informal learning contexts.

5.1 Facilitators – Activity 1

My language picture

My language picture

You will need to prepare:

- materials for drawing

- space for drawing (table or floor)

- a template or a few examples for the language pictures

- an example of your own personal language picture.

1. Ask learners to describe the languages they speak, understand, listen to, read and write.

2. Ask learners when, where and why they use these different languages. This can include family, school, social media, books, advertising, etc.

3. Ask them which languages they are more and less confident to use, and why.

4. Show learners your own language picture and describe it to them.

5. Give learners drawing materials. Invite them to make a picture of themselves and their languages. They can do this in any way they like, such as:

7. Compare the similarities and differences amongst learners.

5.2 Facilitators – Activity 2

My goals and languages I need to achieve them

My goals and languages I need to achieve them

You will need to prepare:

- Examples of people who use different languages in their work (these can be newspaper articles or pictures of famous people, or examples of local people).

- ‘Case studies’ of language learners. We have included some examples for you, in the ‘Further resources’ section.

- Photographs from magazines or newspapers of different career people, to discuss the different languages they use.

More and more employers look for people who can use more than one language so having more than one language is an extra skill to put on a job application.

1. Discuss with learners how many people around the world use more than one language in their work.

2. Read out some examples or have learners read out the examples to the group.

3. Talk together and make a list of people who use different languages in their careers, such as:

- Tour guide

- Lawyer

- Customer service representative

- Airline flight attendant

- Customs officer

- Journalist

- Humanitarian aid worker

- Accountant

- IT and programming

- Translator

- Hotel manager

- Language teacher

- Doctor.

4. Can learners name a famous person who uses more than one language?

5. Do learners know local people who use more than one language in their work?

6. Ask learners to talk about their goals and ambitions, for study, work or travel.

7. Ask them what languages they might need to achieve their goals.

6 Further resources

Translators without borders (2021) Case studies from Africa of language careers: Translators Without Borders. Available at: https://translatorswithoutborders.org/blog/meet-jeff-and-ursuline-supporting-the-african-language-community/

Indeed (2023) Eleven Jobs with Languages. Available at: https://uk.indeed.com/career-advice/finding-a-job/jobs-in-language

Wei, L. (2018) ‘Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language’, Applied Linguistics, Vol. 39(1), pp. 9–30. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039 9 (Accessed: 21 February 2024).

This article argues that the 21st century has made it necessary for us to think differently about language than we have done to date. Because of globalisation, migration and extensive cross-border communication coupled with advances in technology that facilitate multimodal communication, there is a need to reconceptualise language and multilingualism to make it better aligned with the ways in which communication takes place in today’s world. Today, people switch in and out of different ‘named’ languages, e.g. they mix English with Chinese, and they use emojis and post video stories on Instagram, thus blurring the lines between spoken and written modes of communication. For these reasons, there has been a shift within sociolinguistics with researchers increasingly arguing that named language as we used to know them, e.g. ‘English’, ‘Swahili’, ‘Hausa’, ‘Nepali’, etc. are becoming increasingly irrelevant, at least in practice. Of course, ‘named’ languages still play an important role in official policy, for promoting linguistic rights and in peoples beliefs. At the same time, linguistic researchers who used to advocate that it was best if learners were only exposed to the target language when learning languages, this doctrine has over the years, and as more research evidence has emerged, come to be replaced with one where learners are best served by learning through many different languages, as they are wholly capable of telling them apart when they need to.

Erling, E. J., Adinolfi, L. and Hultgren, A. K. (2017) Multilingual classrooms: opportunities and challenges for English medium instruction in low and middle income contexts. British Council and Education Development Trust.

This research report shows how students and teachers across primary schools in Ghana and India engage in ‘translanguaging’, that is they draw widely on features from one ‘language’ or ‘dialect’ to facilitate comprehension in others. This can entail the teacher teaching a topic in English and then grouping students according to their home language and asking them to discuss the topic in their home language. It can also entail drawing on resources from both speaking and writing, e.g. the teacher explaining something to the class in Nepali or Hausa while writing key words or teaching points on the white board in English.

Paulsrud, BA, Zhongfeng, T. and Toth, J. (2021) English-Medium Instruction and Translanguaging. Multilingual Matters.

This book shows how students and teachers across contexts as diverse as Kenya, South Africa, Maldives, Cambodia, Kazakhstan and others engage in translanguaging, i.e. extensive usage of their home language, despite the fact that the classes are officially English-medium. Authors make the point that although translanguaging is sometimes stigmatised or actively discouraged in official language policy, it tends to be used extensively in classroom practices, and often with positive effects of facilitating communication and comprehension between speakers of multiple different languages. Researchers argue that everyone should work to destigmatise language mixing and translanguaging and instead actively promote it in language policy and practice. To support their point, they evidence it with research showing the many positive benefits of translanguaging.

7 References

Hultgren, A. K., Wingrove, P., Wolfenden, F., Greenfield, M., O’Hagan, L., Upadhaya, A., Lombardozzi, L., Sah, P. K., Adamu, A., Tsiga, I. A., Aishat, U., & Veitch, A. (2024). English-medium education in low- and middle-income contexts: Enabler or barrier to gender equality? British Council/The Open University.

8 Acknowledgements

This content has been developed by The Open University, UK, with support from the British Council.

Thanks to everyone who assisted in the authoring, production and editing of these resources, especially students, parents, teachers and head teachers in three secondary schools in Nepal and Nigeria (you know who you are!) as well as our two researchers in Nigeria, Prof. Amina Adamu and Prof. Aishat Umar.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. We will be pleased to include any necessary acknowledgement at the first opportunity.

Images

Course image: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Head teacher and teacher discussing school activities: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Activities for School Leaders 1: EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Activities for School Leaders 2: EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Teacher talking to a group of students in Nigeria: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Temple and worship - image 3: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Temple and worship - image 4: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

City and shopping - image 6: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

City and shopping - image 7: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Boy speaks in favour of English: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Girl speaks against the use of English in class: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Drawing: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Language portrait a: With permission of Lost Wor(l)ds

All videos courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

8 Videos

he draws it.