OER 4 Digital and tech for language and learning

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | English Medium Education and Gender Equality (EMEGen) Open Educational Resources |

| Book: | OER 4 Digital and tech for language and learning |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 23 November 2025, 8:36 AM |

Table of contents

1 Role of digital in girls’ lives

The British Council carried out a global research exercise on the role of digital and technology in the lives of adolescent girls in:

- Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia.

- Bangladesh, Pakistan, India and Nepal.

- Myanmar, Indonesia and Vietnam.

- Syria.

- Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Sudan and Ethiopia.

What is girls’ level of digital literacy and what access do they have to digital technology and platforms?

Read these two excerpts from the 2022 ‘EDGE (English and Digital for Girls’ Education)’ report. As you read, notice the uses of digital and tech for language and communication, and for learning in general. Do you notice similarities or differences to your own context?

You can find the whole report in the ‘Further resources’ section.

Nigeria

Access to digital technology, particularly mobile phones, is widespread across all the surveyed states in both urban and rural communities. Mobile phones are often internet enabled and used to access social media platforms like WhatsApp, YouTube and Facebook. Adolescents mainly rely on mobile phones to connect with friends and peers, meet new people, do school assignments and find information. However, very few adolescents own or have access to personal computers. There is unequal access and use of digital skills between the poor and rich, rural and urban communities, as well as communities in the North and South (Ifijeh et al., 2016; Girl Effect, 2016).

Across the states, the girls expressed enthusiasm to learn, believing that it is important to develop their English and computing skills (including the use of computer applications like Microsoft Excel and Word) in order to interact effectively, boost their productivity and generate additional income. Parents believe their children will benefit and become better people if they can develop digital literacy and digital skills. Another motivation is to be able to complete digital forms themselves, without having to travel far to get help to do so.

(p. 22)

Myanmar

Women in Myanmar are 14 per cent less likely to own a mobile phone than men despite improvements in access and affordability (GSMA, 2020). This gender gap is likely a result of a combination of low household income and traditional gender roles that prioritise men for mobile ownership (Scott, 2017). Rural and ethnic-minority women lack accessible and relevant online content due to higher rates of female illiteracy and the language of the content.

Women’s digital skills are limited, they have less time to explore digital technologies, and they often rely on men to learn ‘how’ to do things on mobiles (GSMA & LIRNE Asia, 2016). Reasons suggested for women and girls’ lack of digital skills include:

- Most girls in rural areas do not know how to use the phone to access the internet or send text messages

- Women work longer hours of unpaid household work and have less time to explore digital technologies than men

- Women’s opportunities for skills training and employment are hampered by restricted mobility, especially in rural and conflict-affected areas

The threat of online violence and the dangers of online dating can lead to parents censoring adolescent girls’ access to digital technologies

Adolescent girls tend to use a family member’s phone, with their access often restricted by fathers who believe that they are protecting them from drugs, being trafficked or being distracted from their studies (Bartholomew & Calder, 2018). For girls who do own a phone, they use them mainly to access Facebook.

(p. 59)

Next, read from global research about girls and mobile phones.

1.1 Global research

In 2018, the Vodaphone Foundation and the Malala Fund carried out global research on girls’ access to and uses of mobile phones. This research found that girls are aware of the positive impact that mobile technology can have on their lives and they are creative in getting access to it.

Look at this data from the report, Real girls, real lives, connected.

Notice the opportunities for language, communication and learning in mobile technology:

|

Phone uses |

Girls who own a phone (n = 351) |

Girls who only borrow (n = 418) |

Girls who own and borrow (n = 181) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Calls |

90% |

69% |

31% |

|

SMS |

65% |

33% |

81% |

|

Games |

35% |

31% |

27% |

|

Entertainment |

43% |

27% |

34% |

|

Radio |

40% |

29% |

26% |

|

|

44% |

21% |

18% |

|

Internet |

42% |

15% |

42% |

|

Calculator |

39% |

17% |

17% |

|

|

31% |

27% |

17% |

|

Banking |

28% |

12% |

41% |

|

Homework/school work |

31% |

15% |

23% |

|

|

24% |

9% |

34% |

|

Dictionary |

22% |

12% |

33% |

(p. 26)

Since 2018, these numbers will have increased.

In your context, what access do learners have to digital technologies and ICTs (information and communication technologies)? Is this different for girls and boys?

What are the opportunities and challenges of digital and tech in your context, for girls and for boys?

In your professional role, how do you use digital and tech?

Now read from the EMEGen research.2 EMEGen research

Teachers are creative in using available ICTs for lesson planning and resources.

I was teaching a lesson on driverless cars in America. I downloaded a video about it on my phone and we watched it together. Students were very interested to see this video – the car is moving without a driver!

(English teacher)

In my school, internet and a projector are available. I connect the projector, and I show students the different industries, small ones and large ones, and the locations on the map. This is good, because I can’t transport students to see these in real life.

(Economics teacher)

I recommend students to learn English by using YouTube videos. I tell them to research a topic further on the internet.

(English teacher)

We live in the 21st century and we are surrounded by technologies. But here we have no equipment or laboratory. So, to demonstrate practical physics and chemistry, I could show videos or pictures that I find on the internet.

(Science teacher)

Teachers use digital technologies to find lesson ideas, resources, and videos or pictures that will inspire students and they use social media platforms to share information and resources.

Teachers will also often use their personal phones and laptops to supplement what is available in the school. For instance, if the school has a projector, teachers can connect their phones to it and show a video or image that they have downloaded.

Access to digital technologies is growing rapidly. ICTs offer many opportunities for school leaders, teachers and students.

With this in mind, now go to your activities.

3 Activities for school leaders

In these activities, you will audit the digital resources that are available to you and to your teachers. You will survey teachers, and see if one or two would become ‘digital champions’ for the school.

3.1 School leaders – Activity 1

ICT Audit

ICT Audit

Make an ICT audit, as a chart or a table with the headings shown below.

|

ICTs in the school |

ICTs that we use personally |

|---|

You can do this as a staff meeting activity, with teachers contributing their ideas or you can do this by informal one-to-one conversations with teachers.

ICTs could include:

- Laptop

- Projector

- Mobile phone

- Bluetooth speaker

- Radio

- Television

- Slide projector

- CD player.

Add resources, software and platforms, such as:

- Internet

- Translation tools

- Text to voice software

- Mapping and directions systems

- Multimedia tools for editing or creating images

- Communications systems such as email, WhatsApp or Telegram

- Resources such as YouTube or government websites.

Do teachers have opportunities for professional learning on digital platforms, such as government websites, WhatsApp or Facebook?

What are the ICTs that seem to be most available, and most used?

3.2 Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be defined as: ‘technologies that mimic human behaviour to conduct tasks normally done by people’ (Edmett, 2023, p. 24).

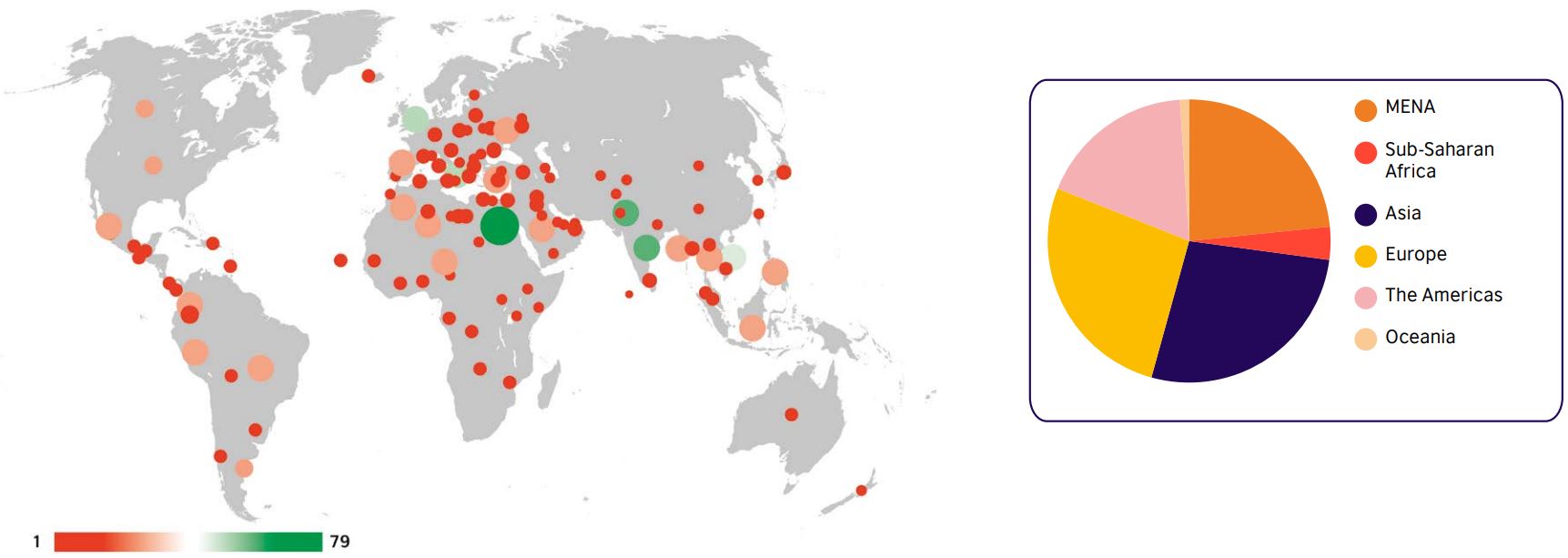

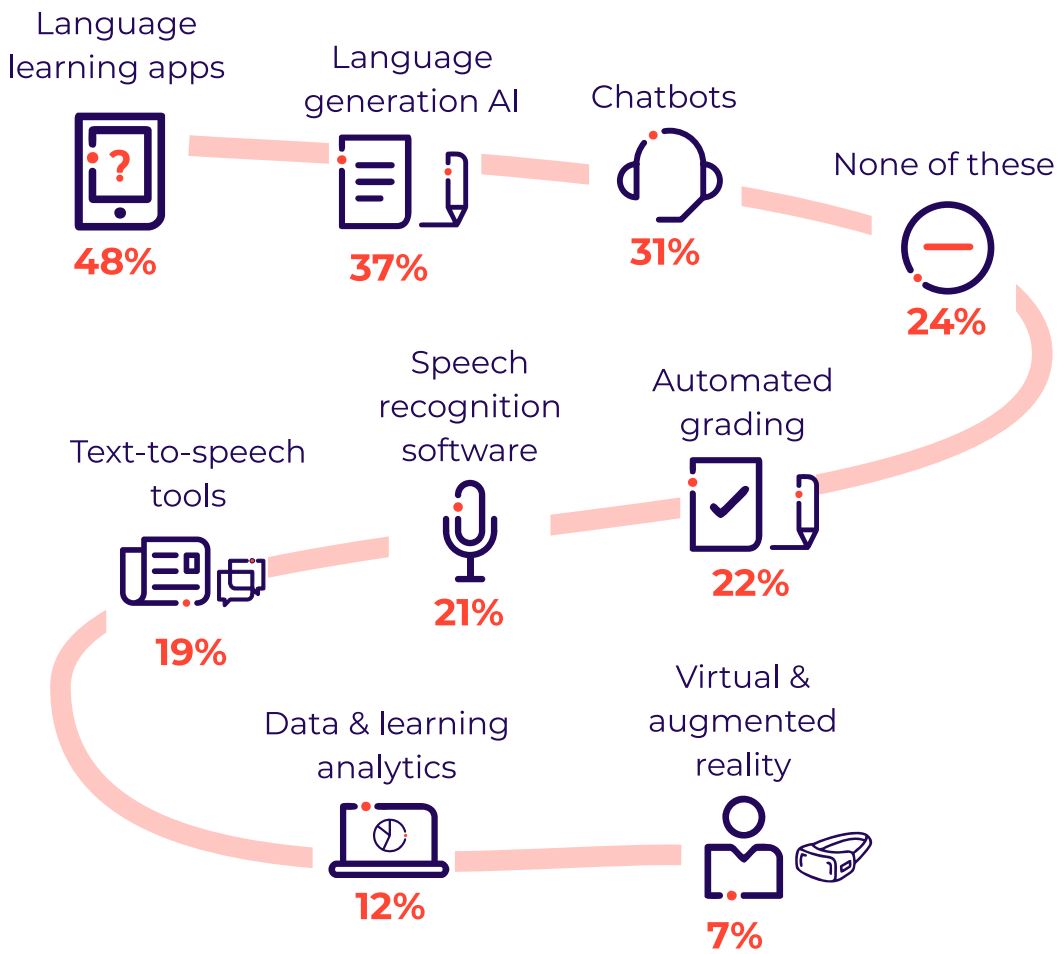

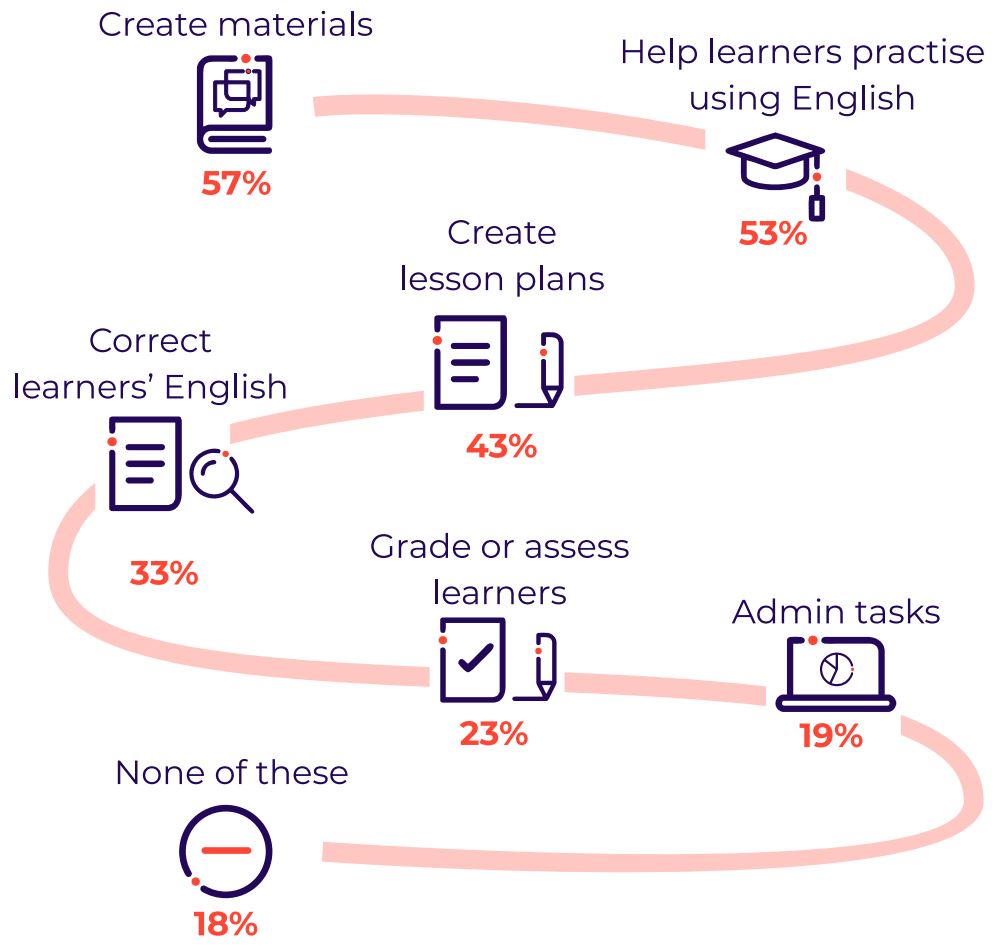

In 2023, the British Council surveyed 1,348 secondary school and university English language teachers from 118 countries and regions about their uses of artificial intelligence (AI) (Edmett, 2023).

33 per cent were teaching in state schools, 23 per cent in private or fee-paying schools, and 22 per cent at a university.

27 per cent of the teachers were from Asia, 27 per cent from Europe, 23 per cent from the Middle East and North Africa, 18 per cent from the Americas, and 4 per cent from Sub-Saharan Africa.

The teachers said that what AI tools they use and how they use them.

Here is what they reported. Do you use any of these tools? Do you know if your teachers use any of these?

The majority of teachers in the survey felt unprepared to use AI in teaching, but many are educating themselves:

I am trying to learn as much as I can by myself.

I have completed online […] courses to develop my knowledge of AI in teaching.

(p. 30)

AI is evolving rapidly and it is likely that you and teachers use AI tools already, such as:

- spell- or grammar-checking that automatically corrects errors

- a chat bot that answers basic questions

- a language app to learn or practise.

There are organisations, such as the British Council, that offer ‘digital badges’ for completing courses, so teachers increase their digital skills and their professional practice at the same time.

3.3 School leaders – Activity 2

Staff survey and digital champions

Staff survey and digital champions

Make a survey of teachers to find out who has good digital skills.

There is a digital audit template from the Digital Heritage Hub and included in the ‘Further resources’ section that you can adapt and use. It covers topics, such as:

- Computer skills

- Social media

- Web-based communications and searching

- Word processing

- Email and chat

- Basic online security.

You can include AI tools and activities such as those listed in the British Council survey of teachers.

When you have done your survey, could one or two of your teachers be ‘digital champions’ for the school staff?

Could you have a female teacher take this role?

Professional women who are confident to use digital technologies can inspire and motivate girl students to develop their digital skills.

Alternatively, are there professional people, women and men in the community who could support staff development?

4 Activities for teachers

The activities for teachers and the activities for facilitators are not activities that are made to be used just once. They can be repeated with variations for different classes and subjects.

Try the activities based on what is possible in your context – you can do an activity for your own personal development, or you can do an activity in the classroom with your students. Try choosing an activity that is new to you or an activity that you would like to become more confident at, then practise the activity before trying it out in your classroom.

You can do an activity on your own, but it can be more fun to try it with other teachers and talk about it together.

If you are already very confident and familiar with these activities, you could support or mentor teachers who are less confident.

4.1 Teachers – Activity 1

Visual resources for language and learning

Visual resources for language and learning

Visual resources are stimulating and reinforcing for language learning and learning in general. Images can:

- support learners at different levels of the language of instruction

- be current and relevant to learners

- illustrate words and ideas

- add interest to your lessons

- show places and people that are far away

- show processes that are not possible in the classroom

- reduce how much you need to talk and explain.

1. Use a phone or other device to download a visual resource. This could be:

- video (e.g. demonstrating a science experiment or illustrating a topic such as driverless cars)

- photographs (e.g. of famous historical figures, or faraway locations)

- artwork to copy or discuss

- graph or chart

- slide show

- map.

2. Then make a plan to integrate the resource into a lesson. Downloading will depend on how large the resource is, and your connectivity.

Have you tried digital tools that can ‘capture’ images without downloading everything? There is a ‘snipping’ tool that is built into most digital devices. Look for the ‘scissors’ icon and practise using it.

You can connect the device to a projector, if you have one, and show the resource on a sheet or wall for students to see and respond to. Students can:

- develop their vocabulary by describing what they see

- ask and answer questions about it

- write about it.

Note: We have seen teachers improvise a projector using a cardboard box and a magnifying glass. In some contexts, there are mobile projectors that are shared in a district or region.

Or, you can have students see the resource in pairs or small groups around the device. If you organise the presentation in this way, have students see the resource and then go off to work on an activity about it.

3. After the lesson, think about:

- How difficult or easy did you find this?

- Did the resource make the lesson more interesting and motivating for students?

- Did the resource make teaching more enjoyable?

Share your resource with colleagues if you have a professional chat group (on WhatsApp, Viber or Facebook, for example).

4.2 Teachers – Activity 2

Audio resources for language and learning

Audio resources for language and learning

Practise your own speaking and pronunciation, and have students practise comprehension, vocabulary, speaking and listening.

Try a speaker

Download spoken poetry, an audio book, a speech, interview or music, and play this through a speaker.

Pause at different points to check students’ understanding or pose questions for them to answer or discuss.

Try a translation tool

This converts one language to another – there are free versions online such as Google translate.

Notice similarities of words in different languages and compare different ways to say the same words or phrases.

If you have access to a projector, demonstrate to students how the tool works and practise vocabulary and phrases in translation.

Try a shared writing activity with the class:

- Have students dictate the lines of a story or a poem in one language.

- Process and read out the translation.

Try a text-to-voice tool

This converts written words into computer-generated speech. There are free versions online and many digital devices now have built-in text-to-voice tools.

Text-to-voice is ‘multisensory’. It allows us to see and hear what we read. This can:

- improve word recognition

- increase the ability to pay attention and remember information

- help us correct our own writing

- improve pronunciation and listening.

5 Activities for informal learning facilitators

Prepare for these activities by knowing how to stay safe online, and how to decide if something online is reliable and trustworthy. There are some suggestions in the ‘Further resources’ section.

5.1 Facilitators – Activity 1

Find out what learners know and use

Find out what learners know and use

Part 1

Where do learners see ICTs being used, for what purposes, and what ICTs do learners have access to?

Adapt and use the Digital Skills Audit (Digital Heritage Hub – also in the ‘Further resources’ section) or adapt the list from the table in the Section 1.

Ask if learners use a mobile phone for any of these?

- Calls

- SMS

- Games

- Entertainment

- Radio

- Internet

- Calculator

- Banking

- Homework/school work

- Dictionary.

Alternatively, you can ask learners to tell or show you as a diagram, by writing lists underneath the headings:

- ICTs that I use

- ICTs that I know about but do not use

- ICTs that my family (parents or older siblings) use but I do not

- ICTs that I would like to learn about.

When you know what the learners have access to, what they would like to know about, and what is permitted to them, you can plan activities for their interests.

Part 2

Ask learners to choose as a group what they would like to learn about when it comes to ICTs. What you do next will depend on what the group decides.

If learners have the same or a similar homework assignment, choose an activity that will help them to work on it.

For instance, learners might know about Facebook, but are prohibited by their parents from using it. In these situations, learners should not do something that their parents do not allow. You can discuss the reasons why parents might prohibit certain platforms or social media.

For another variation of this activity: learners might know about social media or communication apps but are not sure how they work. You can demonstrate some of these, and how learners can stay safe on them. You can show the differences between social media that can be accessed mainly for viewing, such as Instagram, and digital platforms that are mainly for communicating with others, such as WhatsApp.

Learners could be interested in AI but what is it, and how does it work? Learners may have heard about Siri, Alexa or ChatGPT. With a tablet, a bluetooth speaker or a projector, you can demonstrate and discuss these tools.

You could:

- Search the internet using key words (see Activity 2).

- Use an online calculator.

- Look up historical dates or timeline.

- Use a speaker to listen and practise English or another language.

- Listen to an AI programme on a telephone automatic answering system (e.g. ‘Press 1 for yes, press 2 for no’, etc.).

- Look at email formats and how to write an email.

- Try out text to voice software for speaking practice.

- Try out a translation tool for vocabulary practice.

- Experiment with a mapping programme to show directions.

- Travel the world with Google Earth.

- Use a search engine for information about a topic, such as future careers.

- Complete a digital form together.

- How to make a secure password.

- Updating devices and software.

5.2 Facilitators – Activity 2

Searching and reliability

Searching and reliability

1. Discuss basic online safety measures, like:

- Don’t share personal information online.

- Not all downloads are safe and some may contain viruses or malware.

- Public Wi-Fi networks may not be protected by a password.

- Do not click on any ‘pop-up’ ads.

2. Demonstrate how to search the internet using key words or a question by asking learners to choose a topic and find out something about it, using key words or asking a question. For example:

- Question – Who was the first woman explorer?

- Key words – Woman explorer world

Learners can do this in pairs or groups and each pair or group can find out a different fact about a topic. See which key words work better for good results!

3. Discuss how to decide if the information learners find is reliable.

- What is the source of the information?

- Is the source a political party, a charity, a government department, a business, a well-known author, a university or an anonymous person?

- How would we decide what is more and less reliable and trustworthy?

7 References

British Council (2022) EDGE report. Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/2022-04/Girls%27%20education%20and%20empowerment.pdf (Accessed: 22 March 2024).

Edmett, A., Ichaporia, N., Crompton, H. and Crichton, R. (2023) ‘Artificial intelligence and English language teaching: Preparing for the future’, British Council. Available at: https://doi.org/10.57884/78EA-3C69 (Accessed: 26 February 2023).

Girl Effect (2018) Real girls, real lives, connected. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b8d51837c9327d89d936a30/t/5bbe7

bd6085229cf6860f582/1539210418583/GE_VO_Full_Report.pdf (Accessed: 23 March 2024).

8 Acknowledgements

This content has been developed by The Open University, UK, with support from the British Council.

Thanks to everyone who assisted in the authoring, production and editing of these resources, especially students, parents, teachers and head teachers in three secondary schools in Nepal and Nigeria (you know who you are!) as well as our two researchers in Nigeria, Prof. Amina Adamu and Prof. Aishat Umar.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. We will be pleased to include any necessary acknowledgement at the first opportunity.

Images

Table of phone usage (text): Overview of girls' phone usage, by ownership status. Respondents able to select multiple uses (TEGA data, n=880). From Vodafone Foundation and Girl Effect (n.d.) 'Real girls, real lives, connected' www.girlsandmobile.org. Available from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b8d51837c9327d89d936a30/t/

5bbe7bd6085229cf6860f582/1539210418583/GE_VO_Full_Report.pdf [Accessed 22/03/24]

Teacher on phone: Courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)

Image of countries map: British Council

AI diagram 1: Courtesy of British Council

AI diagram 2: Courtesy of British Council

Two

girls sitting in a school looking at a laptop: One Laptop per Child on Flickr

https://www.flickr.com/photos/olpc/4882658643/. This file is available under a

Creative Commons CC BY 2.0 license.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

All videos courtesy of the EMEGen Project (British Council and The Open University)