Scots as a language learning option in schools

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Scots language teacher CPD September 2024 |

| Book: | Scots as a language learning option in schools |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, 21 November 2025, 4:49 PM |

Description

1. Introduction

In this final unit written by Michael Dempster, you will explore Scots as a potential subject area in its own right within schools, where pupils can learn the language, or improve their already existing skills in Scots further. This unit also revolves around multilingual practices in the classroom and what that could mean with regard to Scots in your own teaching context to ensure you create a safe space for learners to use their own voice and language.

In addition, you will find out more about the complexities such an approach brings not only because of the different levels of confidence and proficiency of pupils and teachers, but also due to the negative image that still exists around Scots in educational contexts.

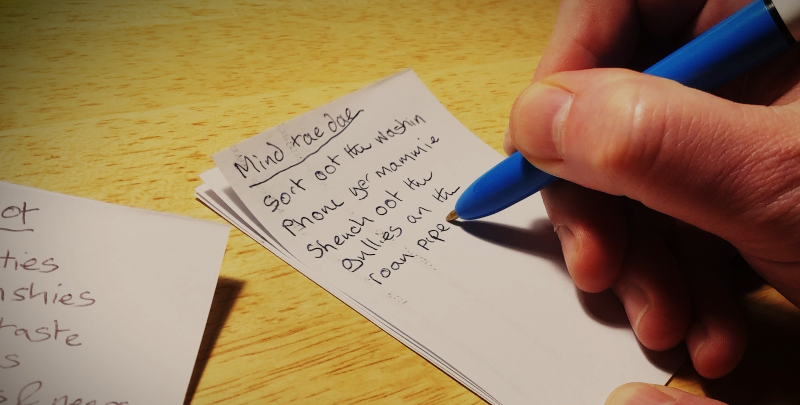

An important point for schools and teachers today is how to represent the sounds of Scots language on the page. This is writing in a non-standard language. Scots does not have a standard or one correct answer for how it should be written. We have seen not only writers across history take different approaches, but even those published as contemporaries take different approaches. This is often down to dialect. It is also down to personal choice and the desire to represent one’s own unique voice. We encourage a similar approach be taken in classrooms today. Many learners’ experience of Scots will be specific to their dialect area. This opens a wide variety of creative opportunities, particularly for creative writing, poetry and fiction.

How to assess or correct writing like this requires a tweaked approach from assessing or correcting writing in a standardised language like English. The reality and lived experiences of learners can be explored here – with the option for schools to link more closely with life outside of education for children and young people. It is their knowledge of language from outside the classroom which learners draw on, just as they do when using their imagination for writing a story or poem. If they have seen Scots written down, that experience helps them to write confidently. If the learners have never seen Scots written before (particularly in a classroom environment) they will require more support. Resources are available on the Scots Language Centre website as well as from Education Scotland, such as 100 key Scots words which is broken down into the different dialects of Scots, for you to use depending on where you and your class are in the country.

Key learning points

- to learn about language standardisation and the development of spelling conventions in Scots

- to understand the importance of dialect diversity for both written and spoken Scots

- to find out about the relationship between Scots and English in the context of creative writing

- to develop teaching ideas and assessment techniques for Scots spelling and pronunciation

- to learn about the role of Scots as one of many languages in a school context

- to understand the impact of multilingual classroom practices on pupils’ attainment and inclusion.

2. Input

Activity 1

To start your study of this unit, we think it will be useful to learn about studying the Scots language to become more fluent and teaching Scots as a language in its own right. To find out more about the discussions around this theme, engage with Unit 4 Dialect diversity of the Open University’s Scots language and culture course to get an introduction to the dialects of the Scots language. Unit 20 Standardisation of the Scots language, also written by Michael Dempster, will provide useful background information on other aspects of what you will be introduced to in this Unit.

Undertake as many activities as you can in the units of the Scots language and culture course, taking notes on aspects that are relevant for the key learning points listed for this unit. You may want to take your notes in the learning log for future reference.

2.1. Activity 2

In this activity you will think about Scots in education and compare your own experiences as a learner/speaker of the Scots language with those Michael Dempster recounts in a recent video.

A.

Before engaging with the input material in this activity, take a moment to consider what might be problems and what might be advantages when introducing Scots as a subject in its own right in Scottish schools.

You

may want to keep a record of your initial thoughts in your learning

log, from your unique subject perspective, and bring these along to

the tutorial to share with your peers.

B.

Watch the first 4 minutes of the video ‘Dignity’ by Michael Dempster, where he introduces his relationship with the Scots language. You may recognise many parallels with your own experiences of Scots – particularly during your own education.

Take

a note of the points he is making that you find most important in

terms of your own relationship with the language and in terms of

teaching Scots, the language your pupils bring to the school, how

they learned it, their attitudes to speaking it etc.

2.2. Activity 3

In

Unit 2 you engaged with the report Scots

language in the Curriculum for Excellence

(2017), which investigated the role and standing of Scots language

and culture in Scottish education. The key finding from this report

is important for the study of this unit:

Scots can support children and young people to develop a range of important skills in literacy, including advanced reading and writing skills required for success in national qualifications. Scots as part of Curriculum for Excellence can support young people in developing their confidence and a sense of their own identity. It can help to engage learners whose mither tongue is Scots by making them feel more valued and included, and therefore more motivated to take part in lessons, to lead learning, and to achieve more highly. (p. 7)

As teachers, you will be deliberating how you can support your pupils in developing the above-mentioned literacy skills when Scots does not have an agreed standard, a set of rules for its use in writing, for example. You might ask how you can be confident in assessing the Scots language outputs your pupils produce and whether there is a right or wrong way of using Scots.

This activity is designed to help you develop your understanding of the close links between Scots and English and help build your confidence in bringing Scots into your teaching.

A.

First of all, read the input text below and take notes on the following aspects explored within it:

Connections between English, Scottish Standard English (SSE) and the Scots language

Considerations for teaching the Scots language

You may want to keep a record of your notes in your learning log. Compare your notes with our model answer.

Although Scots is a non-standard language, it and can be taught formally using techniques available for teaching any other language. Scots is spoken by at least 1.5 million people within and more outwith Scotland. As such it will be the first language of many pupils in Scottish classrooms.

As Scots is a minoritized and largely a spoken language, there are

additional considerations when approaching learning it, compared with

dominant languages. Teachers and pupils alike may fall within a wide

range of levels of proficiency in Scots language production and

comprehension. Identifying a particular level of Scots to be taught

in a particular classroom can therefore be difficult.

Why

is that the case?

Scots

has existed in a state of language contact with English for a number

of centuries. A highly simplified model of the degree to which a

person’s Scots is influenced by language contact is its

‘broadness’. This is often conceptualised as the extent to which

a person’s language deviates from what some consider the prestige

language of Scotland, Scottish

Standard English

(SSE). SSE may be considered Standard English as spoken using the

phonological system of Scots, commonly conceptualised as an ‘accent’.

For

some the replacement of the Scots accent with the accent of Received

Pronunciation (or R.P. as it is commonly known) when speaking English

is the standard that is sought. Historically this type of vocal

production would be learned through elocution lessons, and today

through what is known as accent reduction training. Not only do we

not teach elocution in Scottish education we do not seek to reduce

accents – or allow any discrimination against anyone for their home

language being one other than English. This is the case for children

and young people in Scotland’s schools, as much as it is for adults

living and working in the wider Scottish society today.

As

Scots has been in a state of language contact with English over the

centuries concurrent with the development of modern scientific

linguistics, when teaching Scots as a language we often encounter

what is termed ‘folk

linguistics’

- received wisdom about language which is not derived from current

scientific linguistics. It is worth bearing this in mind as you

explore Scots as a language, often this will yield valuable knowledge

and understanding that can be applied to all language learning.

One

consequence of the over-simplified conception of the continuum of

language varieties is that people believe there ought to be a

distinct cut-off point where English ends and Scots begins.

Becoming

caught up in trying to draw a line on this continuum can be a

stumbling block in language learning, leaning towards a Prescriptive

linguistics, where

one speaks about how a language ought

to be spoken, while descriptive linguistics is where one speaks about

how a language is spoken.

Whilst

prescriptivism may make it easier for a new learner, it may well

alienate the native speaker from their own language. Taking a

descriptive linguistic approach allows the exploration of Scots as it

is spoken. From this stance of linguistic awareness, speaker and

learners alike can use both spoken and written forms of the language

with confidence.

Coming

back to the research on spoken Scots in Scottish classrooms, this

finding from Scots

language in the Curriculum for Excellence

(2017) exemplifies the blurred boundaries between Scots and English

and the fact that these do not impact negatively on teacher and pupil

confidence in using Scots. However, observe the positive impact of

the amount of Scots spoken by the teacher on pupils’ proficiency:

Most teachers observed spoke in

Scottish Standard English whilst speaking to the whole class. They

also used occasional Scots words and phrases. A small number of

teachers spoke extensively in Scots to the class, for example when

giving directions or asking questions. Where this occurred, most

children and young people spoke Scots in response, demonstrating

their understanding of the teacher’s use of Scots and their own

proficiency in using the language. Repeated use in lessons of Scots

words initially unfamiliar to pupils helped them increase their Scots

vocabulary and their confidence.

(p. 5)

B.

Now watch another part of the video Dignity, minutes 4:00 to 9:20. In this section you will hear Michael talk about folk songs, approaches to singing and some of the challenges around these ways of using the Scots language he identifies.

Again,

take notes on aspects that are relevant to you personally and to

teaching Scots in your specific context.

2.3. Activity 4

As writing a language forms an important part of the way we teach languages in educational contexts, you are going to explore written Scots in some more detail. In this activity, you will use examples to find out how the written Scots language evolved, and what particular features it developed, which made it the written Scots language we know today.

Michael

asks an important question in this part of his film, Hou

dae A best write sae thit fowk ken hou tae read oot whit it is that

A’m writin? To answer

Michael’s question, now engage with three input texts in parts A to

C which will provide ideas of how a pupil will write in Scots and how

you can support them in developing their written Scots.

A.

To

start with, read a short summary of the development of written Scots

and take notes of any developments you may wish to discuss with

others on this course.

A historical excursion into the development of Scots

A useful distinction to be made when approaching Scots as a language is to consider it first of all as a spoken language, and that the written language is a complement to a spoken or a gestural language. Written Scots, as is the case with many written languages, is the representation of the spoken language using the technology of the alphabet largely developed to represent Latin.

Written Scots began in the 14th century along with other vernacular literatures such as Italian and Middle English. Foundational works in these languages are The Divine Comedy in Italian by Dante Aligheri completed in 1320, The Brus in Scots by John Barbour completed in 1375, and The Canterbury Tales in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer written between 1387 and 1400. One of the earliest works in Scots is Scotland after Alexander dated to circa 1300.

Written Scots has a continuity through the past 700 years to this day. It reflects changes in the spoken language over that period, as do the vernacular literatures of other spoken languages. All written languages have different influences and processes in their development and usage. When using written Scots in learning Scots as a language it can be useful to understand some of this when introducing a text.

Written Scots was used as a language of record, law, correspondence and literature until the 17th century. During this period conventions of grammar, lexicon and spelling emerged. In the late 17th through the 18th century written English was adopted as the language of record and law. During this period English became standardised and this was the model on which Scottish Standard English emerged as a spoken language.

From the 18th century Scots literature continued with an ideology of revivalism, retaining written Scots’ lexicon and spelling but increasingly becoming influenced by the grammar and spelling conventions of written English. It continued to develop reflecting the spoken language, however increasingly it represented the finer differences of Scots dialects and the innovation of the individual authors.

At various times in the history of the Scots language the adoption of pan-dialectical conventions, which are language principles used across the dialects of the Scots language, have been employed to support the revival and ensure the survival of the language. In these revitalisation endeavours, language conventions were often drawn more from historical literature rather than the spoken language. This has led to what has become known as Literary Scots, where, to a greater or lesser extent, each text stands not as a record of the spoken Scots language, but as a proposition of what Scots, written and spoken, ought to be.

This overview by Michael can help you and your pupils develop writing skills with examples of written Scots through the history of the language.

B.

You will now delve a little deeper into the story of how writing the Scots language on the page began, using materials on the Education Scotland website which were written by teachers in collaboration with scholars at Glasgow University. The resource is a series of lessons providing learners with an introduction to Medieval Britain and Scots language through activities based around Listening and Talking, Reading and Writing.

Go to ‘Engaging with spelling in Scots language - BGE@The University of Glasgow’ and study the lesson ideas, with a specific focus on writing in Scots. You may find it helpful for this activity to look back at lessons you have delivered previously and adapt that lesson plan, rather than create a completely new one. Depending on the age of your class and/or the subject you teach, it may be best to add a Scots element or focus to a lesson you know already works well.

Begin to develop your own lesson idea for writing in Scots which you will bring to the tutorial and take notes in your learning log.

C.

Moving on from looking at the historical aspects of Scots, you will now explore Scots today and how this can feature in your classroom, leading on from your work in creative writing in Unit 5.

Take a note of key points in the input text below and end your engagement with Activity 4.C with Elaine C. Smith’s video and your teaching ideas around this.

Learning Scots as a living language

As a living spoken language one often finds that there is a wealth of linguistic knowledge to draw from Scots within the classroom. Usually, we experience Scots as spoken where we live and as it has not yet been codified it can be best to approach it from this perspective. It may be the case that the pupils have a greater linguistic knowledge of spoken Scots than the teacher, particularly in local dialectical usage. Be prepared to facilitate this. Depending on the age of your class there are a number of ways you can entice learners to share their knowledge of the language, be it sharing stories of community events, or within families, or even by presenting the class with objects or cultural artefacts – this is the approach taken in the Open University Scots Language and Culture course where a ‘handsel’ introduces each unit.

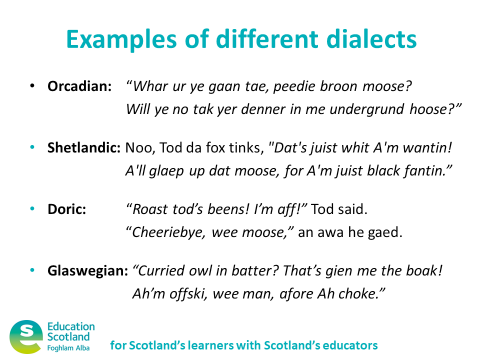

A further option is to use a well-known piece of literature which has been translated into Scots. Here are four examples of a translation of a children’s book into different Scots dialects. Each line is in a different dialect and all come from published translations of Julia Donaldson’s The Gruffalo.

Here you can observe four different authors making different decisions on how to codify their Scots, but all four are going through the same process of mirroring on the page how the people in that area of the country would pronounce Scots, and which words or vocabulary is prominently used there. This approach to writing, used by published authors, is very popular in schools across Scotland. Embracing dialect diversity and pupils’ unique voice has been commended by bodies like Education Scotland and the SQA.

And when it comes to reading the Scots determined by different dialect influences, there are various techniques you can use to assist if you do not understand written Scots. To stick to the examples from The Gruffalo in Scots:

you have the original English text and knowledge of the story;

the fact that the story follows a rhythm and the lines rhyme in couplets;

context clues;

and resources such as the Dictionary of the Scots Language, both the full online version and the Scots Dictionary for Schools App.

Here are activities you can undertake with the resource in this activity.

Choose 4 lines from the Gruffalo in dialect, record yourself speaking them or translate them into English. Your pupils can try the same.

Watch Elaine C Smith’s rendition of The Gruffalo and pay attention to the way in which she uses rhythm and rhyme to pronounce the Scots language.

Depending on the age group and subject you are teaching, either

- take 4 lines from The Gruffalo in Scots and analyse how the poem’s structure helps with the pronunciation of Scots. You can find different versions of the text on the National Improvement Hub: The Gruffalo in Scots ;

- alternatively select a different text to work with, for example from the Scots poetry selection on the Scots Language Centre website.

Find out more about dialect variation and the development of spelling rules in Scots, with resources developed by Michael.

2.4. Activity 5

Although Scots is classed as a non-standard language, this does not mean there are no rules for using it. For example, when it comes to spelling, there are rules which can help you build confidence in reading and writing in Scots.

As you might have discovered in the three parts of Activity 4, there is a close link between spelling and pronunciation which helps develop your mastery of the rules for writing in Scots. For example, lesson 1 of the ‘Engaging with spelling in Scots language - BGE@The University of Glasgow’ highlighted the phonetic approach to spelling in Scots. This is the same approach used in the German language, where words are mostly written as they are pronounced, as showcased in some of the language links in the Open University Scots language and culture course.

This activity is designed to help you create classroom activities based on the information on Scots spelling you will study.

A.

When exploring Scots as a language it is useful to begin at the level of vocabulary.

Often people’s conception of what Scots is, are the words which are perceived as being unique to Scots. Take some time to note down as many unique Scots words as you can think of. There are many thousands of these in common usage. When exploring uniquely Scots words it is useful to consider if these are words specific to a dialect or if they are used in other dialects of Scots. And to go one step further, you might be able to identify, if they exist in other dialects, how do they vary in pronunciation and spelling.

Example: fankle or fangle (verb or noun, see the DSL for various nuances in meaning: to trap, to tangle, to stumble; a tangle/muddle)

You may like to do this activity in your own class.

Start by asking the pupils for a Scots word they know, then discuss how this could be spelled. In this discussion, think again about the question from Michael’s video: How can I write a Scots word so that others can say/read/understand it/Hou dae A best write sae thit fowk ken hou tae read oot whit it is that A’m writin? Also remember the links you have made between spelling and pronunciation in Activity 4. To help you with this activity, explore the list of unique Scots words Michael has collated in his own teaching.

As a second step, you can work with a dictionary to ascertain whether the spelling convention you have come up with is commonly used, and whether the meaning of the word you had in mind coincides with that listed in the dictionary. Use the Dictionary of the Scots Language, both the full online version and the Scots Dictionary for Schools App.

As a final step, think of a way in which pupils can then use these uniquely Scots words in writing, depending on your own teaching context. Then bring your word(s) and activity idea to the Unit 7 tutorial.

B.

A second class of words to consider are those which are related to English words but vary in one or more consonant or vowel sounds. Take some time to note down as many of these as you can think of.

Examples: scoor (Sc.) – scour (Eng.); soond (Sc.) – sound (Eng.)

You could again develop an activity around this for your own teaching.

Study the list of common words with varying spellings in Scots and English provided by Michael to raise awareness of spelling patterns in Scots and English and differences between both that are common. Pupils might even realise that they might have been spelling words in Scots rather than making mistakes in English spelling! By being aware of such common patterns, pupils will have more knowledge to draw on and become more confident in their own work.

Discuss with your pupils good ways of remembering these patterns such as:

Example: oo (Sc.) vs. ow/ ou (Eng.)

Pupils could create posters for display in the classroom, start developing a rule book or other ways to help remembering through visualisation.

Finally, think again of an activity in which pupils use these words, for example writing the same text in Scots and English using such words and bring your idea to the tutorial.

2.5. Activity 6

To gain an understanding of how the basic vocabulary of Scots differs from that of English it can be useful to explore the most frequently used words. In this activity, you will undertake a comparison of the two hundred most common words in English and their Scots equivalents.

A.

Using Michael’s ,

find a unique Scots word,

find a word with the same meaning same but different pronunciation and/or spelling,

find a word with the same meaning and spelling.

B.

What observations can you draw from studying the list and thinking about the three categorisations you worked with in 6.A?

Looking at the Scots words in the table of the two hundred most common words in English you have noticed that some words, when written, are the same as their equivalents in English. It ought to be noted that their pronunciation using the Scots phonological system makes them sound quite different to their pronunciation using an English phonological system. This is of particular note in words containing ‘r’, ‘ch’, or ‘wh’, or where there are different numbers of syllables, such as ‘film’ or ‘medicine’.

With the focus on written language these may be misunderstood as “English words” and Scots words only being those which differ in spelling or which are thought of as being unique to Scots. However, a language is composed of all words and features as they are spoken.

With Scots speakers adopting English for written record and governance, as well as contact with literature and spoken English, it could be argued that all English words have been borrowed into Scots. The important point here in terms of education is that of languages not having borders – certainly not the distinct borders between countries – and that words move as the speakers of languages do. It would be difficult to write an English text where no words are used which have been borrowed from other languages, so when using Scots in the classroom the approach should not be one of trying to create a Scots-only text. Writing in Scots should be about opening doors to new vocabulary and creativity, and that doesn’t require putting the English words out as you go.

2.6. Activity 7

In this activity you will explore the wider connections of Scots with other languages and how these are reflected in the language itself.

We often compare Scots only with its major contact language, English. This can re-enforce the view that it is merely a set of exceptions to Standard English. However, it is both historically related to and has been influenced by most of the neighbouring languages of Western Europe, and those further afield.

A.

In developed by Michael, you find many Scots words relating to the common social and physical environment of Northern Europe. These are placed in the context of English, Norwegian, Dutch, German, French, Italian, Scottish Gaelic, Irish and Welsh.

Now explore the table and compare Scots words with these other languages. Then try to answer the following questions:

How do the written words compare?

Can you see the relationship between Scots and other languages?

Do the vowels change, and the consonants remain the same?

Do consonants change in regular ways?

Is Scots sometimes closer to languages other than English?

This type of comparison across related languages can help place Scots in context and aid learning of other modern languages.

B.

In this part of the activity, we ask you to start developing a teaching idea based on what you learned in part A.

Continue working with body parts and try out the following:

Pupils find examples in table they want to work with.

Depending on the age and literacy skills, pupils could:

record a video talking about body parts in different languages

create a poster labelling the body parts in different languages

write a language link like the ones on the Open University course explaining the links between languages in the names of body parts

produce a skills strategy for learning the names of body parts in Scots and how knowing the names of body parts in different languages can help learning these in speaking and in writing.

Then take a note of what you tried out, or plan to try out and reflect on possible challenges and impact of the activity.

3. Tutorial

Activity 8

As in previous units, the tutorial is designed to provide a space for the discussion of key questions from the unit with your peers, to share ideas you developed when studying the unit input section and to start planning your application task.

In the tutorial your own assumptions and experiences will play an important role and the discussion will build on Higgins and Ponte’s (2017) finding that ‘the teachers’’ own linguistic histories strongly shaped their views about multilingualism in schools, [and] that a formally sanctioned opportunity to experiment with multilingual pedagogies opened up new spaces for critical self-reflection about the links among languages, teachers’ identities, and academic engagement for multilingual learners’ (p. 15).

A.

Go through your notes from Activities 1 to 7 and select key thoughts you noted down about:

teaching Scots as a subject in its own right in Scottish schools,

teacher confidence in using, teaching and assessing Scots in the classroom,

important steps that need to be taken to build pupil confidence in using Scots in the classroom and developing their Scots literacies.

Bring these to the tutorial for discussion.

B.

Closely related to the approach of teaching Scots as a subject in its own right, is another concept, namely that of Scots being a crucial aspect of multilingual practices in the classroom in Scottish schools.

Read our summary of research on multilingual classroom practices and take notes to bring to the tutorial discussion of:

important findings from the research mentioned here,

your own thoughts related to this about your and maybe also your colleagues’ teaching practice and context,

the role of Scots alongside other languages pupils bring to the classroom – can Scots lead the way here for the embedding of multilingual classroom practices?

Multilingual classroom practices – pros and cons

Moore and Vallejo (2018) highlight reasons why multilingualism has been mostly absent in our classrooms:

‘A large body of research has demonstrated that the plurilingualisms and pluriliteracies that children and youth bring to classrooms are often not those required for school success. This is even more so for students from underprivileged backgrounds, a demographic where children and youth with family backgrounds of immigration are over-represented. [...] Thus, paradoxically, students who are ‘pre-equipped’ with diverse communicative repertoires that could be used to the benefit of their education, and of society, are often vulnerable to poor school results’ (p. 25).

Contrasting that, there is a growing body of research investigating the benefits of bringing multilingual practices to the classroom. Findings from such research show how important it is to incorporate home languages in the classroom to activate prior knowledge. In his article ‘Why mixing languages can improve students’ academic performance’ Rasman (2021) identifies three key advantages of utilising pupils’ multilingual skills in the classroom:

‘multilingual skills help students to activate their prior knowledge, which positively affects the process of understanding new knowledge;

multilingual skills help build rapport between students and teachers, which is important for improving academic performance;

multilingual skills help increase students’ well-being, which is a key factor in successful learning.’

Lompart (2022) in a recent ground-breaking edited volume on plurilingualism in education, reports findings from a collaborative plurilingual classroom project where teachers and pupils learn with and from each other:

‘All in all, the analysis of the data has shown how by positioning students as participants and as experts in their languages, Urdu, in this case, the traditional knowledge asymmetry associated with classroom talk is changed and the youth can take up roles as experts and thus direct the teaching activity and introduce metalinguistic reflections. Actually, the adult’s admission of her lack of competence in the Urdu language […] accounts for the youth’s participation and transformation into teachers and experts. (p. 63)’

Lompart concludes that plurilingual practices in the classroom ‘subvert the traditional class dynamic […] by giving value to the students’ plurilingual repertoire and by situating them as full participants and agents in their process of learning. [… The lesson design] set out from the crucial idea of understanding that the students are experts in their respective languages and that their knowledge is valid for academic work. (p. 63)’

Wagner’s (2021) investigation into teacher practices that can support multilingual learners highlights the role of the teacher modelling in building learner confidence and challenging their own assumptions about classroom language use. He emphasises that ‘nurturing multilingualism starts with creating spaces in which students are comfortable and empowered to use all of their languages. Doing this required making the use of multiple and non-English languages routine and using them in ways that had meaning and significance in the classroom’ (p. 6). An important finding from Wagner’s research, that has often been debated in the context of teaching Scots, is teacher proficiency:

‘For teachers, stoking language curiosity in children did not require being proficient in the languages their students spoke. […] In many of these examples, supporting students’ curiosity required both questioning and moving past teachers’ own assumptions and preferences about how to use language, an obstacle that […] can limit teachers’ use and encouragement of multilingualism in the classroom. A willingness to move beyond their own comfort zone was part of how these teachers were able to see, recognize, and encourage the language practices that excited and motivated their students’ (p. 9).

Coming back to literacy development in multilingual settings, in our case writing in Scots, Wagner (2021) underlines that allowing multilingual outputs is an important building block for pupil confidence and development in all the languages they are using. He states: ‘[W]hen writing, […] teacher encouragement to make active choices led some children to produce multilingual texts. Across classrooms, teachers shared similar stories about how the “decision to allow students to choose their language preference […] made learning more fun and comfortable for them” (Teacher 4, Interview)’ (p.10).

C.

As the final step to prepare for the tutorial, you are going to engage with an impactful school-university research partnership between Banff Academy and The Elphinstone Institute at Aberdeen University that investigated the influence of teaching Scots on pupils' self-esteem and wider achievement, using Participatory Action Research and creative arts to explore attitudes to Scots in school.

Watch the presentation by the two primary investigators, PhD student Claire Needler and teacher Jamie Fairbairn, at the FRLSU conference 2021. (Note: should you be asked for a password, please use: FRLSU_202!)

When watching the presentation take a note of findings from the partnership on one or more of the following:

the approach and methodology that was used in the project,

how the project created spaces where ‘critical questioning of the world’ was possible,

how positive attitudinal change and encouraging the pupils to view the Scots language as a valuable part of both their cultural heritage was achieved,

the role the creative arts played in this process,

how the project aims (fostering inclusion, developing literacy, boosting cultural knowledge and inter-generational communication) were achieved.

3.1. Lesson planning

Activity 9

To prepare for the tutorial, start preparing your own lesson by writing the activities and learning outcomes you plan to include – use the ideas for your own lesson based on what you studied thus far in this unit. You may wish to refer to the ‘3-18 Literacy and English Review’ as well as the Education Scotland resources.

Continue the lesson planning after you have discussed your ideas during the tutorial.

The CfE Experiences and Outcomes for Literacy and English should be referenced as often as possible.

Compare your lesson plan with our .

Key aspects to consider when planning a Scots language lesson or activity

You now need to consider what you need to do before you can use your lesson plan in the classroom. Identify what you will need, say, why, and plan which order you will structure the activities.

Education Scotland have prepared word lists for the various regional varieties of Scots which you may wish to use as a guide to Scots vocabulary suitable for classrooms across the country depending on where your school is.

Each lesson should be planned using the experiences and outcomes document. These describe the knowledge, skills, attributes and capabilities of the four capacities that young people are expected to develop.

The CfE Benchmarks set out clear statements about what learners need to know and be able to do to achieve a level across all curriculum areas. Here are the Literacy and English Benchmarks.

Learning in the broad general education may often span a number of curriculum areas (for example, a literacy project planned around science and technology might include outdoor learning experiences, research and the use of ICT). This is likely to be in the form of themed or project learning which provides children and young people opportunities to show how skills and knowledge can be applied in interesting contexts. The term often used for this is interdisciplinary learning and Scots language opens a wealth of possibilities for such lessons. See 'Fresh approaches to Interdisciplinary learning' for more on IDL best practice.

Should you need further inspiration, the ‘Scots Blether’ on glow has a resources section where teachers from all across Scotland have posted lesson plans and activities as well as links to teaching material from other organisations: https://glowscotland.sharepoint.com/sites/staff/scotsblether/SitePages/resources.aspx *this link requires you to be signed into glow

Don’t forget to share examples of the fantastic teaching and learning going on in your classrooms. Share on social media using #OUScotsCPD, and tagging us in your posts @OUScotland, @OULanguages, @EducationScot.

4. Application

Activity 10

Using the notes and ideas that you began to gather during the tutorial, complete steps 1–5.

In your own time, continue planning your chosen activity, adding more detail where required.

Try out the planned activity with your learners. You might want to gather some feedback from your learners about the activity as well, which you can bring to the module and share with your fellow students.

Write an account of 250–300 words, highlighting the successes and challenges you encountered when applying what you have learned in terms of pedagogy and language. It may be helpful to consider these questions:

What do you think worked particularly well in your classroom application?

Is there anything you would do differently if you were to repeat this lesson?

What are the next steps for your learners?

How will you provide further opportunities to practise and reinforce what was learned?

Then post your reflective account in the Course forum. Read and comment constructively on an application task post by another colleague.

Don’t forget to share examples of the fantastic teaching and learning going on in your classrooms. Share on social media using #OUScotsCPD, and tagging us in your posts @OUScotland, @OULanguages, @EducationScot.

5. Professional Recognition

This reflective blog post should be informed by your learning across units 1–7. You should write critically and in some depth about your development across the course of the whole programme.

You are encouraged to:

revisit and review the coaching wheel you completed during Induction

consider the extent of the interconnections between the language and pedagogy strands

outline the next steps for you as a teacher of languages.

Your post should:

be 750–1000 words in length. You may write a longer contribution if you wish.

be informed by your learning since the start of this programme and look forward to the next steps for your professional development in terms of Scots language and culture teaching pedagogy

address the programme’s three Master’s level criteria:

Knowledge and understanding

Critical analysis

Structure, communication and presentation.

In writing your post, you may choose to:

use one or more prompts from the bank of reflective prompts provided to frame your writing

make connections between readings and your practice

explore the extent to which you feel surprised/impressed/disappointed or something else by an aspect in your coaching wheel.

Finally, post your reflection in your Reflective blog.

6. Community Links

Still from Wandering Oisin HOME | scotsoperaproject

The Scots Opera Project

The Scots Opera Project is an arts organisation based in the West of Scotland which presents opera and classical music in Scots. Creative director and tenor David Douglas formed the arts organisation in 2014. The company consists of a core of professional singers and instrumentalists, librettists creating original translations of classical repertoire in Scots, and composers interpreting existing Scots texts.

Watch the news item from ITV news about the project to get a first impression about the project and the challenges of performing an opera in the Scots language – Michael Dempster features too.

Now read Michael’s observations:

Each production works with a community chorus who attend an intensive course supported by vocal coaching and language coaching. In addition to this outreach workshops engage with community arts organisations for set design and schools with singing and Scots language activities.

Productions thus far include Scots translations of Charpentier’s Actéon, and La Descente D’Orphée Aux Enfers, (Christopher Waddell) & Mozart’s The Magic Flute, and Purcell’s Dido & Aeneas (Dr Michael Dempster.) Working with composer Alan Fleming Baird The Scots Opera Project have performed his original opera Tannahill, and his new operatic version of Robert Burns’ ‘The Jolly Beggars’.

In my role as librettist and language coach I have had the pleasure of working very closely with a wide variety of professional singers and highly skilled amateur singers. It is often a very mixed group with broad Scots speakers, Scottish Standard English speakers who have a high comprehension of Scots through to those who have little comprehension, and first and second or other language English speakers.

We work on singing in a Scots accent, having developed a method similar to what you find in the established operatic languages, and Scots language comprehension, to enable singers to interpret the meaning of the libretto and act the song.

Singing in a Scots accent is a learning experience for most singers, regardless of their linguistic background, as we often learn to sing in accents that are not those which we use for speech. Some features we explore are the sounds of Scots, stress patterns, syllable count. One feature in particular is the vowel sound in words like ‘wife’, ‘side’, and ‘Clyde’ which are part of spoken Scots accents, but are rarely sung as the distinction between, for example, ‘side’ and ‘sighed’ is not present in other accents used to speak English.

Scots language comprehension can be an excellent group experience as many participants have full knowledge of the meaning of the text and others find it completely opaque. I facilitate company and chorus members in sharing the meanings of words, phrases and complete songs with one another, serving to give authoritative answers only when the group are not able to arrive at a consensus. In a classroom setting this approach is useful to draw from the linguistic expertise pupils bring with them.

As I write the libretti in a pan-dialectical Scots this accommodates dialect variation within principle singers and the chorus. When we have performed in different areas of Scotland, we are able to discuss the dialectical variations in the small number of words where this comes up. We settle upon the pronunciation local to the performance. For principle singers we discuss the appropriate dialect for their character and invariably they wish to sing in their own dialect. For example, in The Magic Flute the singer who played Pappageno described himself as a Doric speaker and chose to sing ‘wh’ words with an ‘f’ and alter the vowel sounds of the handful of variant words to North East Scots. Pappagena sang in her Ayrshire dialect.

Participants regularly feed back very favourably on the course and there is a very high return rate at subsequent productions. Those who didn’t speak Scots often report their delight in being able to engage with the linguistic culture of the place they have made home. Those with Scots accents and those who speak Scots frequently identify it as a transformative experience that validates their own voice and accent. All participants go on to sing in Scots and with a Scots accent in their own work away from The Scots Opera Project productions rightly identifying singing in Scots and with a Scots accent as a valuable skill to proudly include in their performance range.

“It’s a really interesting way to sing. It’s not something I’m used to, which is odd because [given] our accent and the way we speak it kinna comes naturally once you speak it. But combining that with operatic singing, it’s really interesting.” - Stephanie Strachan, Soprano and participant.

7. Research

Activity 11

To develop a better understanding of the challenges around literacies development in indigenous languages in educational contexts, read the study '“I Learned That My Name Is Spelled Wrong”: Lessons from Mexico and Nepal on Teaching Literacy for Indigenous Language Reclamation' (2021) by de Krone and Weinberg, who have drawn conclusions that are highly relevant for teaching writing in Scots.

This well-written article will provide an excellent context for your teaching of creative writing in Scots as it promotes the acceptance for variety and writer voice and choice in writing indigenous non-standardised languages.

Read the article and take notes that will help you answer the question the authors pose at the start of the article: What are the opportunities and challenges of teaching writing in support of endangered language revitalization and reclamation?

Take notes on the following aspects of indigenous language writing in school contexts:

- opportunities

- challenges

- literacies aspects

- experiences

- lessons learned

Now read our and compare this with your own notes.

8. Further Engagement

To read more about the experience of Scots speakers coming to voice:

- Tett, L. and Crowther, J. (1998) ‘Families at a Disadvantage: class, culture and literacies’, British educational research journal, 24(4), pp. 449–460. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192980240406.

To find out more on Scots grammar:

Dempster, Michael (2020) ‘Scots language an accent - web version 1.0’, MindYerLanguage Videos - https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmk3hiyUEgWl7Qa9pBGN3r94ahQiSXJ2U

Teaching resources - https://independent.academia.edu/DempsterM

Purves, David (1997) ‘A Scots Grammar’

Rennie, Susan and Matthew Fitt (1999) ‘Grammar Broonie’

Robinson, Christine (2012) ‘Modren Scots Grammar’

Wilson, L Colin (2002) ‘Luath Scots Language Learner’

For more advanced research in this area

Corbett, John, J. Derrick McClure and Jane Stuart-Smith (2003) ‘The Edinburgh Companion to Scots’

Macafee, Caroline (2011) ‘Characteristics of non-standard grammar in Scotland (1980, revised c. 1992, edited 2011)’ https://www.academia.edu/38768063/Characteristics_of_non_standard_grammar_in_Scotland

Millar, Robert McColl (2018) ‘Modern Scots – An analytical Survey’

To find out more about Scots vocabulary:

Dempster, Michael (2020) Scots Language in comparison with English, Norwegian, Dutch, German, French, Italian, Gaelic, Irish & Welsh - https://www.academia.edu/43927407/Scots_Language_in_comparison_with_English_Norwegian_Dutch_German_French_Italian_Gaelic_Irish_and_Welsh

To read more on the History of Scots:

Dictionary of the Scots Language - https://dsl.ac.uk/about-scots/an-outline-history-of-scots/

The Scots Language Centre - https://www.scotslanguage.com/articles/node/id/117/type/referance

For more advanced research in this area

Jones, Charles (1995) ‘A Language Suppressed’

Millar, Robert McColl (2020) ‘A Sociolinguistic History Of Scotland’

Corbett, John (1997) ‘Language & Scottish Literature’

To find out more about approaches to language revival and revitalisation:

A free course on language revival by the University of Adelaide: Language Revival: Securing the Future of Endangered Languages - Learn how the world’s endangered languages are revived and why this process is critical to preserving cultural identity.

To learn more about multi-/plurilingual classroom practices and the importance of local connections:

Read the open access articles:

Plurilingual Classroom Practices and Participation Analysing Interaction in Local and Translocal Settings Edited By Dolors Masats, Luci Nussbaum (2022)

Florence Bonacina-Pugh (2020) ‘Legitimizing multilingual practices in the classroom: the role of the ‘practiced language policy’, International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23:4, pp. 434-448, DOI: 10.1080/13670050.2017.1372359

Dixon, Kerryn (2018) ‘Seven reasons for teachers to welcome home languages in education’, British Council, 8 August [online] Available at https://www.britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/reasons-for-teachers-to-prioritise-home-languages-in-education (accessed 02 December 2021)

To undertake some textual analysis to investigate the history of the Scots language, here is an activity for you:

Activity 11

Read the three versions and take a note for the main similarities and differences you spot in the three versions of the extract in terms of spelling as well as use of vocabulary or any other feature that you think stands out when comparing the texts.

Also, try to read the three texts out loud using the note underneath to help you with the Scots pronunciation. Reading a text out loud can support your understanding of the words, especially as Scots does not have a written standard.

Scotland After Alexander (c.1300) |

Scotland Efter Alexander (Modren Scots) |

Scotland after Alexander (Modern English) |

Qwhen Alexander our kynge was dede, |

Whan Alexander oor king wis deid, |

When Alexander our king was dead, |

That Scotlande lede in lauche and le, |

That lead Scotland in law an beild |

Who lead Scotland with law and protection |

Away was sons of alle and brede, |

Awa wis skreeds o yill an breid, |

Gone was the abundance of ale and bread, |

Off wyne and wax, of gamyn and gle. |

o wine an wax, o gemm an glee |

and wine and wax, and game and glee |

Our golde was changit in to lede. |

Oor gowd wis chynit in tae leid, |

Our gold was changed into lead, |

Christ, borne in virgynyte, |

Christ, born in virginitie, |

Christ, born in virginity, |

Succoure Scotlande, and ramede, |

Succour Scotland, an remedie |

Succour Scotland, and remedy |

That stade is in perplexite. |

Thon state is in perplexitie. |

That state is in perplexity. |

*Note that in the original text ‘Qwh’ is the older spelling of ‘wh’, and that ‘our’ is pronounced oor and ‘dede, brede and lede’ are pronounced ae which by 1500 was the ee of ‘deid’, ‘breid’ and ‘leid’ (lead).

9. References

Costa, James (2015) ‘Can Schools

Dispense with Standard Language? Some Unintended Consequences of

Introducing Scots in a Scottish Primary School’, Journal

of Linguistic Anthropology,

25, 10.1111/jola.12069.

De Korne, H., & Weinberg, M. (2021). “I Learned That My Name Is Spelled Wrong”: Lessons from Mexico and Nepal on Teaching Literacy for Indigenous Language Reclamation. Comparative Education Review, 65, 288 - 309.

Dempster, Michael (2021) ‘Dignity’, 3 September [online] Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=GkKmoGn0YfY&t=547 (accessed 16 August 2024)

Dijckmans, Lorenz (2016) ‘Scottish language subordination and revitalisation in multilingual UK: Eye on Scots and UK education’ [online] Available at https://www.academia.edu/30916516/Scottish_language_subordination_and_revitalisation_in_multilingual_UK_Eye_on_Scots_and_UK_education

(accessed 16 August 2024)

Education Scotland (2017) ‘Scots Language in Curriculum for Excellence’ [Online] Available at https://education.gov.scot/nih/Documents/ScotsLanguageinCfEAug17.pdf (16 August 2024)

Education Scotland (2021) ‘Engaging with spelling in Scots language - BGE@The University of Glasgow’, National Improvement Hub [online] Available at https://education.gov.scot/improvement/learning-resources/engaging-with-spelling-in-scots-language/ (16 August 2024)

Folk linguistics - Wikipedia (16 August 2024)

Higgins, Christina and Ponte, Eva (2017) ‘Legitimating Multilingual Teacher Identities in the Mainstream Classroom’, The Modern Language Journal, vol. 101, issue S1, pp. 15-28. Available online at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/modl.12372

Llompart, Júlia (2022) ‘Students as teachers, teacher as learner - Collaborative plurilingual teaching and learning in interaction’ in Dolores Masats and Luci (eds) Nussbaum Plurilingual Classroom Practices and Participation - Analysing Interaction in Local and Translocal Settings, Abingdon, New York, Routledge, pp. 54-65. Also available online https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-edit/10.4324/9781003169123-7/students-teachers-teacher-learner-j%C3%BAlia-llompart?context=ubx&refId=242cbd2b-ef96-4c96-99f9-bcedc4933fb3

(accessed 16 August 2024)

Macafee, Caroline (2010) ‘Introduction’, Lallans [online] Available at https://www.academia.edu/98155460/Introduction (accessed 16 August 2024)

Moore, E. and Vallejo, C. (2018) ‘Practices of conformity and transgression in an out-of-school reading programme for ‘at risk’ children’, Linguistics and Education, 43, 25–38.

Needler, C.L. and Fairbairn, J. (2021) ‘How Do You Feel About the Language That You Use?': Promoting Attitudinal Change Among Scots Speakers in the Classroom. In Transformative Pedagogical Perspectives on Home Language Use in Classrooms (pp. 151-171). IGI Global https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/how-do-you-feel-about-the-language-that-you-use/262275. (16 August 2024)

Needler, C.L. and Fairbairn, J. (2021) ‘Scots language teaching: The transformative potential of an inclusive approach to home languages’, FRLSU conference 2021 [online] Available at https://cast.itunes.uni-muenchen.de/clips/HfapxzrO6U/vod/online.html (accessed 16 August 2024)

Nordquist, Richard (2020) ‘Prescriptivism’, Thought&Co. [online] Available at https://www.thoughtco.com/prescriptivism-language-1691669 (accessed 16 August 2024)

Rasman (2021) ‘Why mixing languages can improve students’ academic performance’, The Conversation, 26 October [online] Available at https://theconversation.com/why-mixing-languages-can-improve-students-academic-performance-170364 (accessed 16 August 2024)

Scots Opera Project [online] HOME | scotsoperaproject

Scots Language Centre ‘Scots poetry’ [online] Available at https://www.scotslanguage.com/articles/node/id/96 (accessed 16 August 2024)

Scottish Standard English [online] Available at https://www.scots-online.org/grammar/sse.php (accessed 16 August 2024)

Smith, Elaine C. (2020) ‘Elaine C Smith reads The Glasgow Gruffalo’ [online] Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=hq8zxYnWRW8 (accessed 16 August 2024)

STV News (2017) ‘Opera in Scots’, 5 September [online] Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IlUgr6fPxBg (accessed 16 August 2024)

Wagner, CJ. (2021) ‘Teacher language practices that support multilingual learners: classroom-based

approaches from multilingual early childhood teachers’, TESOL Journal, p.e583. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.583 (accessed 16 August 2024)