Nature recovery

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Introduction to Rewilding |

| Book: | Nature recovery |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 2:49 AM |

Introduction

Genista sp. shrub vegetation natural recovery, Pyrenean oak plantation, Serra da Malcata Nature Reserve, Greater Coa Valley, Portugal Credit: Juan Carlos Muñoz / Rewilding Europe.

In Module 1 you learned about natural processes and how rewilding works to restore them.

In this module we will explore:

- Potential barriers to the restoration of natural processes.

- Different ways rewilding can help nature heal itself.

- How people and natural processes can coexist in Europe.

Rewilding is about working with nature to restore natural processes that are missing or degraded.

If humans can recognise and restore these natural processes, then nature can function as it should, allowing it to support life in all its breathtaking diversity.

The restoration of natural processes can deliver wide-ranging benefits to people. But with many Europeans only now learning to live alongside wild nature once again, nature recovery can often lead to challenges.

Rewilding can help to transform these challenges into opportunities. Measures to promote human–wildlife coexistence, revitalise cultures and traditions, support the development of nature-based economies and harness the wide range of other benefits that nature recovery can deliver, all have a role to play.

![]() Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

After completing this module, you should be able to:

- Explain how rewilding aims to restore natural processes with minimal human intervention and describe the role of ecological integrity in ecosystem health.

- Reflect that nature recovery can generate both challenges and opportunities.

- Evaluate how rewilding's various tools and approaches can transform challenges into opportunities, and how different tools and approaches are applicable in different contexts.

- Evaluate the importance of identifying and removing artificial barriers to enable the recovery of natural processes.

- Evaluate the impact of species translocations in situations of poor connectivity and analyse the effectiveness of focusing on keystone species to restore ecosystem functionality.

1 Core concepts

Across Europe, many natural processes have been disrupted or completely removed from the landscape by human intervention – particularly since the industrial revolution.

Humans have:

- Cultivated huge tracts of land, introduced non-native species, deforested old-growth areas, and replaced broadleaf woodland with coniferous plantations.

- Dammed, widened, and straightened waterways, burned peatland, and drained wetlands.

- Built infrastructure such as roads and railways that prevent wild animals from roaming across the landscape.

- Reduced wildlife populations to very low densities, even in protected areas.

1.1 Working with nature

In general, European nature is managed and controlled to a huge extent. There is a belief that people need to manage nature, and we are perhaps afraid of what might happen if we don't.

Rewilding is about working with nature, not against it. It's about using nature's immense power to revitalise itself, supporting the restoration of natural processes so that they can breathe new life into ecosystems and enable them to function as they should.

A key principle of rewilding is acknowledging that nature may not need our continuous intervention, and that it can lead its own recovery.

1.2 Defining ecological processes

The presence or absence of particular natural processes in an ecosystem reflects its overall health, functionality, and resilience to external influences such as climate change.

In rewilding, we use the concept of ecological integrity. This is a measure of the health of an ecosystem. It takes into account three variables: trophic complexity, dispersal, and natural disturbance.

How do we define ecological integrity?

Trophic complexity

First, what is a trophic level? A trophic level is the group of organisms within an ecosystem which occupy the same level in a food chain.

So, trophic complexity is a measure of the species present within the different trophic levels of an ecosystem. High trophic complexity means that there are a wide range of species at different trophic levels, such as plants, herbivores, carnivores, scavengers, and decomposers.

Dispersal

This is a measure of the ability of a species to move to another area, which lowers competition and can increase genetic diversity. Animals may need to disperse regularly in search of food, shelter or a mate.

Dispersal also allows organisms to escape circumstances which may affect their ability to survive or thrive, such as habitat degradation caused by human activity or less favourable conditions caused by climate change. Infrastructure such as cities, agricultural fields, dams, roads and fences, as well as artificial light and sounds, can act as barriers to dispersal. Increasing connectivity by creating nature corridors or dam removal can increase dispersal.

Natural disturbance

This is a measure of factors causing natural change in ecosystems, such as floods or wildfires. However, humans intervene in natural disturbance because of how it may affect them. Through rewilding we can increase natural disturbance by restoring natural river dynamics or enhancing natural grazing.

The diagram above highlights the interconnectedness of dispersal, trophic complexity and disturbance in maintaining ecological integrity. Ecological integrity improves from left to right.

Measuring changes in ecological integrity over time can help those involved in rewilding understand the impact of their efforts. You will see this term come up again in Module 4.

1.3 Bringing back natural processes

In Module 1 you learned that most European landscapes have been heavily degraded by human intervention. Negative impacts are particularly apparent if we examine change over extensive geographical areas or over significant timescales.

One fundamental role of people involved in rewilding is to look at a particular area of land or sea and work out which natural processes are degraded or missing. The best ways of restoring these processes can then be identified.

Natural process restoration can then enhance the health and functionality of the land or sea in question.

Which natural processes are degraded or missing?

|

Rewilding lets nature lead, so our first approach is to work out how we can act on opportunities to restore natural processes and kick-start nature recovery. It's important to bear in mind that all the interventions taken at the start of a rewilding initiative are designed to lead towards a point where those interventions are no longer required and where healthy nature looks after itself.

Rewilding is not about restoring a picture that then needs curating – it's about creating fully functional natural systems that can sustain themselves.

1.4 Opportunities for nature recovery

Transforming challenges into opportunities

In conservation, the focus is often on responding to threats to nature and biodiversity. The aim is to reduce pressure on nature and protect it. But rewilding is different – it's not about reducing threats to nature, but harnessing opportunities to restore it.

Many threats offer opportunities and if we look for opportunities the world around us might look different.

So, there is a key question that needs to be asked at the start of any rewilding journey. How can we turn challenges into opportunities? How can we bring seemingly opposing interests together and co-create a way forward by providing innovative solutions?

Here are a few examples of how rewilding transforms challenges into opportunities.

Rural depopulation and land abandonment

Rural depopulation is often seen as a problem because of its negative environmental, socio-economic, and cultural impact. Trends such as diminishing employment prospects, increasing dependency on subsidies, and the erosion of social cohesion and cultural heritage, mean areas and communities affected by rural depopulation often face a very unsustainable outlook.

But less pressure on the land also provides new opportunities for nature and wildlife populations to recover. New nature-based economies can be built on recovering natural assets, providing jobs and income that enable people to stay in and repopulate communities. The return of young people and families to such communities can breathe new life into areas and generate pride in the natural landscape.

Flooding

The regulation of rivers and increasing periods of heavy rainfall mean the risk of hugely damaging floods has grown along many European rivers. Rewilding can lead to win–win situations by giving rivers more space to flow naturally.

The removal of embankments helps to restore river dynamics and other natural processes, which can:

- allow alluvial forests to come back on land that seasonally floods

- reduce flood risk for towns and villages by retaining more water in the flood plain

- create recreational areas

- enhance biodiversity by creating different water dynamics and habitats that provide nursing, feeding or nesting grounds for many species.

This approach has been used on many Dutch river floodplains with hugely beneficial results.

Forest management

Europe has very little natural forest left, however forest cover has increased by 5.5% since 2020 (Eurostat, 2024). Many of these new forests have been planted, while in mountainous areas most of the regeneration has happened spontaneously as grazing pressure from livestock is removed. Bringing back large wild and semi-wild herbivores in such places can create healthy, functional mosaic landscapes that are rich in biodiversity, less susceptible to catastrophic wildfire, and more resilient to factors such as climate change and disease.

Wildlife comeback

Europe has witnessed the comeback of many wildlife species since the 1970s, thanks to legal protection, habitat restoration and reintroduction efforts. From beavers, otters, red deer and wild boar, to lynx, eagles, wolves and vultures, this comeback is very encouraging as it proves that nature can bounce back if we let it (Ledger et al., 2022). Since many Europeans have become accustomed to the absence of wildlife (see shifting baseline syndrome in Module 1) they are now struggling to find ways to live with it. As a holistic approach, rewilding supports people to understand the return of wildlife, protect themselves and their assets, and find new ways to benefit from their new situation. Nature recovery can support the growth of nature-based tourism businesses, which provide jobs and income to rural communities, creating economic incentives for people to live alongside wildlife once again.

Cities and urban places

Many cities are becoming less comfortable places to live due to climate change. Concrete and stone buildings, asphalt, and pavements without vegetation are becoming increasingly inhospitable places as summers become longer and hotter. By greening cities with wilder urban parks, trees, flowers, and free-flowing waterways, we can lower temperatures, support the return of wildlife and enhance the health and wellbeing of urban residents.

1.5 Barriers

Aerial view, Distributary channel of the Danube River flowing into the Black Sea, Danube Biosphere Reserve in Danube delta. Credit: Andrey Nekrasov

At the start of practical rewilding initiatives we may need to intervene to create the right conditions for nature to restore itself. This frequently involves removing artificial barriers that have been created by people in the landscape. While many of these barriers are now old and obsolete, they still prevent natural processes from functioning as they should and stop wildlife from moving freely.

Examples of such barriers include:

- Artificial dams, levees, or dykes that prevent flooding, erosion, and deposition, or drainage channels that remove water from natural wetlands.

- Roads, railways, power lines, and fences, which cut through landscapes and prevent wildlife from moving and seeds from dispersing.

- Areas where intensive production is taking place, such as highly managed monoculture plantations, or over-hunted or over-grazed areas that offer little beneficial habitat and which prevent the natural regeneration and dispersal of plants and animals.

- Shipping lanes at sea, where the marine environment is highly disturbed and species such as whales and dolphins are often killed or injured by ship strikes.

|

Another example is the restoration of Arctic rivers in Sweden's Nordic taiga landscape, which you will learn more about in Module 6.

Absence can be a barrier

Barriers may be the presence of something that prevents natural processes from taking place but the absence of a natural element within a landscape can also act as a barrier.

The absence of carcasses in a landscape prevents many natural processes from taking place. When animals die in nature their carcasses are consumed by scavengers like vultures, foxes, and an array of insects, which are part of intricate local food webs. Eventually, aided by the action of microorganisms and fungi, the decomposition of once-living flesh returns nutrients to the soil which then helps new plants to grow, providing food for living animals.

This chain of interactions is referred to as the ‘circle of life’. As you can see from the diagram below, the absence of carcasses can negatively impact entire ecosystems.

The role of large mammal carrion can be considered a keystone. A taurus carcass can trigger a series of natural processes and interactions called ‘Circle of Life’. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

1.6 How can we remove barriers to natural processes?

Rewilding is bold and ambitious, but it is also practical. There are different factors that affect which barriers can be removed, and in what order. Some of these factors are below. .

Prevention first

You learned earlier that infrastructure such as dams, canals, roads, and railways can harm nature and prevent natural processes from functioning as they should. It's important that these barriers to let nature recover and heal itself are removed, where possible.

It's also important that we look to the future and see what opportunities lie ahead. A recent report commissioned by WWF estimates that European countries are using between EUR 34 billion and EUR 48 billion in subsidies each year in ways that may damage the environment, including new infrastructure (Vandermaesen et al., 2024). To support recovery of nature, new infrastructure must be designed to allow wildlife, seeds and natural processes to continue.

Removing barriers that already exist

When it comes to taking opportunities to remove barriers in a landscape or seascape, a range of factors must be taken into account. These include:

|

2 Letting nature lead

Taking advantage of opportunities to kick-start nature recovery can lead to the restoration of some natural processes that were previously present and also help to establish new ones.

Removing a dam changes the way water flows, enabling new interactions between freshwater plants and animals. It also allows a river to resume its role in the downriver dispersal of waterborne sediments and seeds.

Preventing boats from mooring on a sensitive seabed can allow seagrass beds to recover. This provides essential spawning grounds for fish, helping fish stocks to recover, with knock-on effects throughout the food web.

Allowing carcasses to remain in the wild can re-start the circle of life, helping scavengers return to an area. It can also boost populations of invertebrates, which lock up carbon in their shells and help to transfer nutrients from the carcass to the soil.

The phrase ‘passive rewilding’ is sometimes used to refer to humans stepping back, scaling down or ceasing management, and allowing space and time for nature to recover. This cost-effective approach can be very successful where barriers to natural processes are few, and there is already some heterogeneity (diversity or variety) within the landscape and connectivity with other areas.

Leaving deadwood in forests and rivers is a simple way of reducing human management and restoring natural processes.

2.1 Case study

When dead wood is left in rivers, it serves as a vital component of the ecosystem by providing resting and observation spots for birds and dragonflies, as well as egg-laying sites for insects, fish, snails, and dragonflies. It forms the base of complex food webs that include myriad wildlife species, such as diatoms, insect larvae, fish, ospreys, herons, and otters.

Bryozoans (simple aquatic invertebrates), sponges, and caddisflies attached to the wood enhance water quality. Deadwood offers numerous hiding places for young fish and helps to create variation in the river bed.

The key role of dead trees in rivers. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

2.2 How can we measure the recovery of nature and natural processes?

In 2018, a novel approach for measuring and monitoring progress in rewilding was developed by Torres et al., focusing on the ecological attributes of rewilding.

The ‘Rewilding Score’ – a framework for assessing the recovery of natural processes – evaluates two variables:

- Changes in human forcing (intervention in) ecological processes. This is the extent to which people control or modify natural processes. Changes in the ecological integrity of ecosystems.

- This rewilding assessment framework is innovative because it links changes in human forcing to the recovery of nature and natural processes.

Visual representation of the concept and examples of rewilding score against two axis – Human Intervention and Ecological Integrity.

The assessment of a rewilding score combines ecosystem observation and expert dialogue, based on indicators for each of the two axes. Through this process, it also helps identify new potential rewilding actions, including steps to stop or reduce human intervention that can enhance ecological integrity.

Ecological integrity indicators:

- Terrestrial species composition

- Spontaneous vegetations dynamics

- Harmful invasive species

- Aquatic landscape connectivity

- Terrestrial landscape connectivity

- Natura pest and mortality regimes

- Natural fire regimes

- Natural avalanche and rockslide regimes

Human intervention indicators:

- Deadwood removal

- Carrion removal

- Harvesting of aquatic wildlife

- Harvesting of terrestrial wildlife

- Area of mining and intensity of impact

- Grassland area for hay, crop production and intensity of management

- Forest area for silviculture and intensity of management

- Cropland area and farming intensity

- Population reinforcements

- Artificial feeding of wildlife

Other types of monitoring can also deepen our understanding of the functionality of nature, such as:

- sediment loads and erosion/deposition volumes along a rewilded river

- demographic and behavioural monitoring of recovering keystone species

- changes in vegetation heterogeneity using satellite images of the landscape over time.

These, and many other approaches, help to give us a better understanding of the impact of rewilding efforts.

3 Give nature a helping hand – bringing back wildlife

To kick-start and speed up the nature recovery process, we often need to give nature a helping hand, particularly at the start of rewilding initiatives. This can go beyond addressing the presence or absence of barriers. If an ecosystem and its wildlife populations are too degraded, simply letting nature lead may not be enough to restore functionality, or it will take too long for the restoration process to have a meaningful impact.

This is particularly true when it comes to wildlife. Poor connectivity and large distances between existing populations frequently make it impossible for animals to recolonise areas on their own. Beavers in the UK would never have been able to return without reintroductions. In these situations, rewilding efforts can help to kick-start nature recovery by translocating absent animal species, if the conditions for those species to return are favourable.

Dung beetle on cattle dung having been released at l'Étang de Cousseau (Cousseau dunes and wetlands). Credit: Neil Aldridge / Rewilding Europe.

You learned in Module 1 that rewilding focuses on the ecological role of animals and the natural processes that they enhance, rather than their conservation status.

Rewilding is concerned with what an animal does, not necessarily what it is. Often these two are the same, because when an animal is endangered and missing from many places, its functional role in the ecosystem will also be missing from those places.

But there is a difference.

3.1 Keystone species

From a rewilding perspective some of the most important animals are keystone species. These are organisms that have a disproportionately large effect on their natural environment relative to their abundance. The same species may be a keystone species in one context and not in another, depending on the habitat and which other species are present. Some examples of keystone species are:

- European bison in forest mosaic landscapes

- Eurasian beavers in riverine landscapes

- whales in the ocean.

Keystone species not only exert their effects downwards from the top of the food chain, as is the case with predators such as wolves and lynx, but also upwards from the bottom, as is the case with beavers and rabbits. A wide range of organisms including plants and fungi can also be considered keystone species.

The loss of keystone species such as wolves, beavers, or mycorrhizal fungi, can cause an entire ecosystem to collapse. Helping a keystone species return to an ecosystem and thrive within it can have a hugely positive ecological impact and benefit countless other wildlife species.

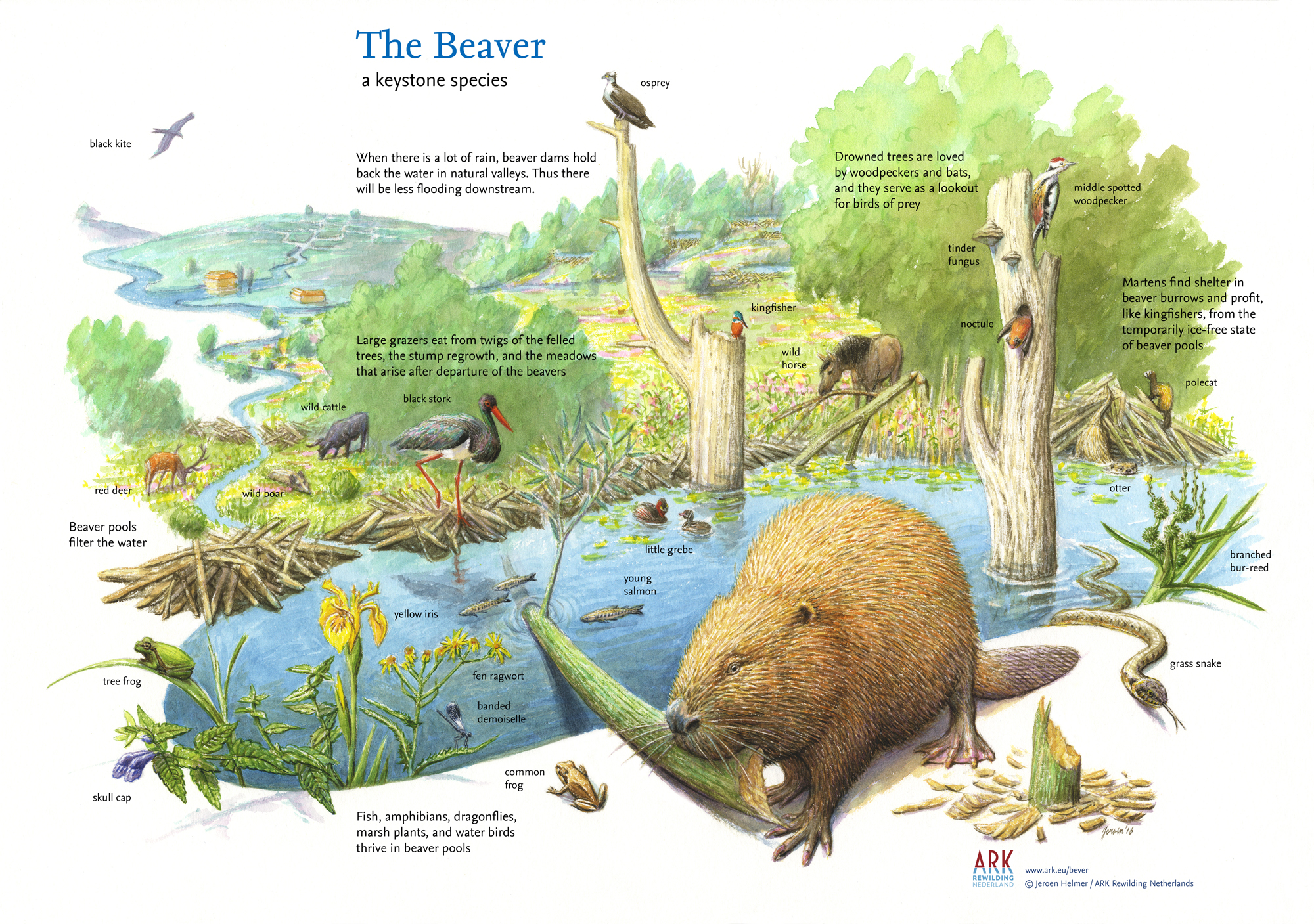

Beavers: an example of a keystone species

Consider what happens in nature when a beaver fells a tree.

- The tree falls and floods part of the river.

- This creates a pond, which attracts insects and fish.

- These attract birds, which carry seeds, which grow more trees.

- These help to mitigate the effects of heavy rains, which may stop the flooding of towns and villages – and so the whole, interrelated system continues.

This gives a clear illustration of how both nature and people benefit from the presence of one or more keystone species.

The beaver: A keystone species. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

Click here for an enlarged version of the above image.

Forest dynamics in a stream valley with a beaver pond. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

|

3.2 Species translocations

Species translocations involve the movement of wildlife species including animals, plants, or fungi, by people, from one place to another. Translocations can be beneficial when it’s unlikely or impossible for a species to return to a rewilding site, due to the extent of local extinctions or barriers that we cannot remove, like mountains or seas. Translocations can also be used to enhance the growth and health of a small existing population – this is called restocking.

In passive rewilding, wildlife species return by themselves, and people have no say in this process. In active rewilding efforts like species translocations, people make choices about what wildlife to move, when, and where to. In reality, many species can and will come back on their own, if the necessary conditions for that species to survive and thrive are present.

When making decisions about supporting spontaneous wildlife comeback, or active reintroductions and population enhancements, rewilders consider which natural processes are missing from or degraded in an ecosystem. Then they can identify which species would be best suited to restoring them. In an area where large herbivores are already present, the ecosystem could benefit from scavengers such as vultures to eat the carcasses, and dung beetles to assist with the breakdown and distribution of the dung.

When looking at the role of wildlife in its natural environment, it's important to look at how groups of species interact with each other. These groups are called ‘guilds’ or ‘assemblages’. A guild of herbivores comprising of species such as European bison, deer, and semi-wild horses, will have a certain impact on a landscape. If only one species is present the impact will be different.

Herd of 17 Konik horses from Latvian nature reserves was released by Rewilding Ukraine on Ermakov island in the Ukrainian Danube delta to maintain mosaic landscape and biodiversity through natural grazing. Credit: Andrey Nekrasov / Rewilding Ukraine.

The selection of which wildlife to translocate as part of a rewilding initiative should consider many different factors, including:

- Whether the species was once naturally present in the area.

- How the presence of the translocated species may impact other wildlife species in the area.

- Whether the current state of the habitat in the new site is suitable for all life stages of the species, and how the habitat may evolve in the context of climate change.

- Whether stakeholders connected to the area where the proposed translocation will take place will welcome the selected species, or if there will be resistance and coexistence issues.

- What economic impact it will have.

- Whether there is a source population in the wild or in captivity from which individuals can be transported, with a healthy genetic base.

- What permits are needed for the selected species in the source and recipient countries.

- If the knowledge, skills, and equipment are in place to capture, move, and release the species at the time and place(s) needed.

These questions are typically answered as part of a feasibility study, which explores and assesses whether it is possible and advisable to move forward with a translocation. This study considers biological feasibility, genetic considerations, animal welfare, and social and legal feasibility, following guidelines established by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The legalities surrounding translocations can be complex. Public and private lands may require different permits. The legal status of a particular wildlife species can relate to factors such as whether it is endangered and if it is considered native to a country. This can affect management requirements and permits. Such status will vary by country and by species and different permits may be needed for capture, holding, transport, and/or release. This makes the translocation process complex.

A Eurasian lynx is released from a crate by Wildlife Comeback Officer Wiebke Brenner in the Oder Delta, Poland. Credit: Neil Aldridge / Rewilding Europe.

Some wildlife species are considered wild, while others are considered domestic, even if they roam free in the wild. This classification determines which animal health laws apply to each species and therefore how much handling of the animals is legally required. It can also affect who is responsible for their management once they have been released (e.g. hunters for so-called ‘game’ species).

4 Module summary

In this module you have learned that rewilding focuses on restoring natural processes with minimal human intervention, allowing ecosystems to recover on their own. It emphasises ecological integrity, which includes trophic complexity, connectivity and natural disturbance regimes as indicators of ecosystem health.

The process begins by identifying opportunities and developing collaborative solutions that benefit various stakeholders. Removing artificial barriers helps natural processes recover and enables wildlife to thrive. When natural return of wildlife is not possible due to poor connectivity, active measures like species translocations, especially of keystone species, are used to restore ecosystem functionality.

![]()

Now that you have completed this module, you should be able to:

- Explain how rewilding aims to restore natural processes with minimal human intervention and describe the role of ecological integrity in ecosystem health.

- Reflect that nature recovery can generate both challenges and opportunities.

- Evaluate how rewilding's various tools and approaches can transform challenges into opportunities, and how different tools and approaches are applicable in different contexts.

- Evaluate the importance of identifying and removing artificial barriers to enable the recovery of natural processes.

- Evaluate the impact of species translocations in situations of poor connectivity and analyse the effectiveness of focusing on keystone species to restore ecosystem functionality.

Next, we will look deeper into how rewilding engages people and communicates its messaging.

4.1 Further reading

The Lifescape Project Rewilding law (n.d.) Available at https://lifescapeproject.org/rewilding-law/ (Accessed 15 April 2025)

Dando,T.R., Crowley, S.L., Young, R.P. Carter, S.P. and McDonald, R.A. (2023): Social feasibility assessments in conservation translocations. In: Trends in Ecology & Evolution, May 2023, Vol. 38, No. 5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2022.11.013

Rewilding Europe (2023) 'Go with the flow: river rewilding in Swedish Lapland', Rewilding Europe [Online]. Available at: https://rewildingeurope.com/BLOG/GO-WITH-THE-FLOW-RIVERS-REWILDING-IN-SWEDISH-LAPLAND/ (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

4.2 Module 2 quiz

Now it’s time to complete the Module 2 quiz – it’s a great way to check your understanding of the course content.

This quiz contains 5 questions and a pass mark of 60% and above is required if you'd like to be awarded your Module 2 – Nature recovery digital badge.

You can review the answers you gave, and which were correct/incorrect, after each attempt has been completed.

If you don’t pass the quiz at the first attempt, you are allowed as many attempts as you need to pass.