Terrestrial rewilding

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Introduction to Rewilding |

| Book: | Terrestrial rewilding |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 2:45 AM |

Table of contents

- Introduction

- 1 European forests in context

- 2 Forests and natural processes

- 3 Ways of restoring natural processes in forests

- 4 Case study: productive forests and natural processes

- 5 Grasslands

- 6 Rewilding terrestrial landscapes: an integrated approach

- 7 The benefits of terrestrial rewilding

- 8 Coexistence

- 9 Module summary

Introduction

Bison in De Maashorst, The Netherlands. Credit: Hans Koster.

In recent decades Europe has witnessed a notable expansion in wooded areas and grassland, primarily due to the abandonment of agricultural land. This trend is largely driven by economic shifts, rural depopulation and changes in agricultural policies which have made farming less viable in certain regions, particularly in remote and mountainous areas.

As agricultural landscapes are abandoned, natural processes of succession take over leading to gradual natural regeneration. This natural reforestation can have ecological benefits, including increased biodiversity, improved soil health and enhanced carbon sequestration. The return of grasslands and wooded areas provides new habitats for a variety of plant and animal species, enhancing the overall ecological richness of the landscape.

One of the most exciting opportunities presented by this expansion in wooded areas and grassland is the potential for rewilding. Newly abandoned areas in Europe offer prime conditions for rewilding initiatives to support the recovery of wild nature.

![]() Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

After completing this module, you should be able to:

- Determine what rewilding principles are most relevant and suitable to rewilding terrestrial landscapes.

- Explain the ecological, social, climatic and economic importance of forests and grasslands ecosystems.

- Assess the impacts of key threats to terrestrial ecosystems and how they disrupt natural processes.

- Compare the differences and similarities between rewilding in grasslands and in wooded areas, and their connections to each other and the wider landscape.

- Evaluate the role of keystone species and natural processes in maintaining healthy terrestrial ecosystems.

- Analyse case studies of rewilding forests and grasslands in Europe.

- Articulate the challenges and opportunities associated with wildlife comeback and select appropriate locally led positive coexistence measures.

1 European forests in context

Old-growth forest reserve, Velebit mountains Nature Park, Croatia Credit: Staffan Widstrand.

Europe has lost nearly all of its primary forests, which are natural ancient forests, untouched by significant human activity. Their disappearance is largely a result of centuries of agriculture, urbanisation, logging and industrialisation. The loss of these pristine forest ecosystems means Europe now lacks many native habitats crucial for biodiversity and natural ecological processes.

This context is essential for understanding the importance of rewilding efforts across Europe, which aim to enable natural regeneration and allow ecosystems to function independently. Without primary forests, rewilding provides an opportunity to rebuild self-sustaining habitats that can support diverse wildlife, enhance ecosystem resilience and help to address climate change.

1.1 Types of European forest

Historically, Europe was once covered by vast expanses of forest. These ancient woodlands were home to a diverse array of flora and fauna, including large mammals such as European bison, wolves and bears. As human populations grew and civilisation advanced these forests were gradually cleared for agriculture, settlements and industrial use. By the Middle Ages, huge swathes of primary forest had been converted to farmland or used for timber and fuel.

Wild horses living wild in the Campanaruis de Azába Reserve, Salamanca, León, Spain. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

Today, the forests that remain in Europe are largely secondary or managed forests. Secondary forests are those that have regrown after being cleared or those that have been significantly altered by human activity. Managed forests on the other hand, are actively maintained and harvested for resources such as timber, pulp and non-timber forest products.

These forests are often planted with specific tree species and managed to optimise economic return which means they typically have less biodiversity than natural forests and have a lower capacity to absorb and store atmospheric carbon.

Learned land abandonment, particularly in remote areas, has also resulted in an increase of wooded areas and new opportunities for rewilding.

2 Forests and natural processes

Aerials over the Letea forest, Danube delta rewilding area, Romania. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe

Despite the lack of primary forests, Europe's forested landscapes still play a critical role in the environment and economy. They provide essential ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, water regulation, soil protection and habitat for wildlife. Forests also offer recreational opportunities and cultural value, contributing to the wellbeing of European societies.

Despite the value of European forests, historical and ongoing human management means natural processes are often missing or significantly degraded. These processes are crucial for maintaining ecological dynamics, biodiversity, and ecosystem services such as carbon capture.

Click on the icons below to learn more about some of the natural processes that are potentially missing.

You will learn more about some of these important natural processes in this module.

Forest fragmentation

One of the main ecological constraints of European forest ecosystems is their fragmentation. Many forests are divided into small, isolated patches which can hinder the movement of species and reduce genetic diversity.

In addition, many ‘forests’ are in reality monoculture plantations managed for timber production, where natural processes are prevented from taking place. This has a negative impact on biodiversity as well as ecological resilience and functionality.

The impact of climate change

Climate change poses another significant threat to Europe's forests. Rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events can stress forest ecosystems and make them more susceptible to pests and diseases.

Shifting climate zones mean habitats that were once suitable for specific tree species gradually become unsuitable, meaning trees effectively need to migrate, which is very difficult as trees are static and their dispersal is often constrained by forest fragmentation.

2.1 Deadwood

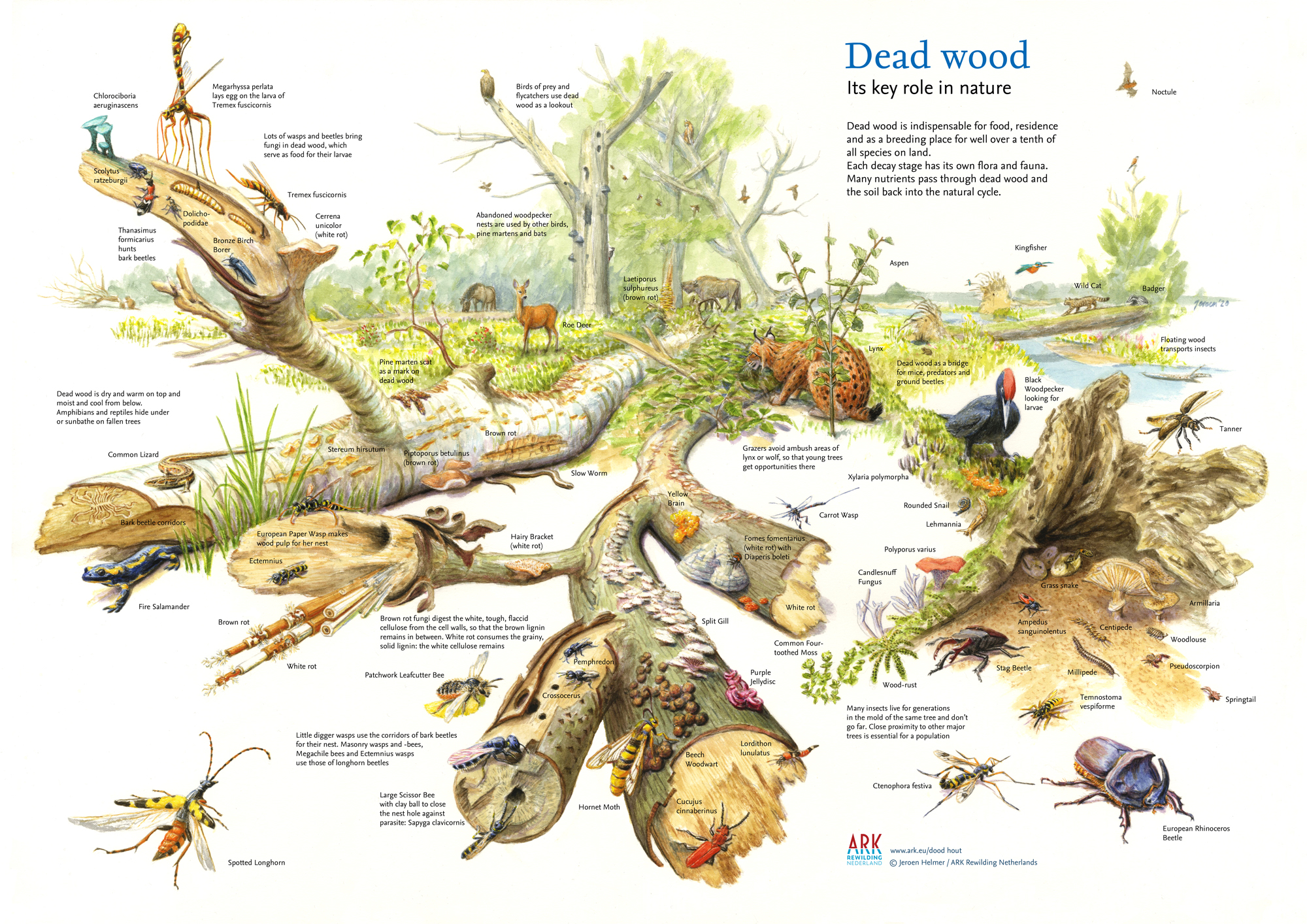

Deadwood can be standing (snags) or lying (fallen logs). Both are critical components of forest ecosystems as they provide habitat for a wide range of organisms, including fungi, insects, birds, and mammals.

Deadwood is essential for nutrient cycling as it decomposes and returns nutrients to the soil. In many managed forests, deadwood is removed to reduce fire risk or for aesthetic reasons, leading to a loss of biodiversity and ecological functions.

Dead wood: Its key role in nature. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

2.2 Bark beetle outbreaks

Bark beetle outbreaks are natural disturbances that play a significant role in forest dynamics. These insects help to create gaps in the forest canopy, allowing light to reach the forest floor and promoting the growth of diverse plant species.

While bark beetle outbreaks can be devastating in the short term, they contribute to long-term forest health and resilience. In managed forests, efforts to control bark beetle populations can disrupt these natural processes and reduce habitat diversity.

Result of bark beetle work, North Velebit National Park, Croatia. Credit: Staffan Widstrand.

2.3 Grazing, wallowing, and tree breaking

Large herbivores (e.g. deer, bison, and wild boar) engage in activities such as grazing, wallowing, and tree breaking, which create a variety of habitats and promote plant, insect, bird, and fungi diversity. These activities help to maintain open areas within forests, which are important for many species.

In many European forests the absence or low density of large herbivores due to hunting or habitat fragmentation limits these natural processes, leading to more homogeneous and less dynamic forest structures.

Soil disturbance and its key role in nature. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

3 Ways of restoring natural processes in forests

Rewilding wooded areas in Europe involves reintroducing natural processes that have been disrupted or eliminated by human activities.

This section details some of the ways of restoring these processes.

3.1 Veteranisation of trees and leaving deadwood

Veteranisation involves artificially creating features in trees that mimic the characteristics of ancient or veteran trees, such as cavities, dead branches and decaying wood. This practice can accelerate the development of habitats for species that depend on old trees.

Leaving dead wood, both standing and lying, is crucial as it provides habitat for fungi, insects, birds and mammals, and plays a key role in nutrient cycling and soil health.

Old-growth pine forest, Stora Sjöfallet National Park, Laponia UNESCO World Heritage Site, Sweden. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

3.2 Thinning plantations and allowing natural regeneration

Thinning involves selectively removing trees from dense plantations to reduce competition and allow more light to reach the forest floor. This encourages the growth of a diverse collection of plants beneath the canopy and promotes natural regeneration.

By allowing natural processes to take over, forests can develop a more complex structure and greater biodiversity. Thinning helps transition monoculture plantations into more natural, mixed-species forests.

Pyrenean oak and Lygos / Retama monosperma in Sierra de Gata, Salamanca Region, Spain. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

3.3 Allowing bark beetle infestations

Bark beetle infestations are often seen as destructive but they are a natural part of forest dynamics. Allowing these infestations can create gaps in the canopy, promoting the growth of diverse plant species and providing habitats for a wide range of wildlife species.

Allowing infestations is an example of letting nature lead by reducing human management and control and allowing natural processes and dynamics to take place.

Result of bark beetle work, North Velebit National Park, Croatia. Credit: Staffan Widstrand.

3.4 Restoring populations of large animals

Reintroducing or reinforcing populations of large herbivores, like deer, bison, wild horses, and semi-wild bovines can significantly impact forest structure and dynamics.

In Milovice, Czech Republic, large animals have been reintroduced to graze, wallow and break vegetation, creating a mosaic of habitats. These activities help maintain open areas, promote plant diversity and create conditions for other species to thrive.

Large herbivores also play a role in seed dispersal and nutrient cycling which further enhances ecosystem health.

|

4 Case study: productive forests and natural processes

Pro Silva's win–win approach

Pro Silva was founded in Slovenia in 1989 and is an organisation that advocates close-to-nature or continuous cover forestry as an alternative to clearcutting.

Through its network of practitioners across 25 countries, Pro Silva demonstrates how productive forestry and the conservation of the forest ecosystem can coexist, which involves managing forests in a way that mimics natural processes (Pro Silva, 2012).

In practical terms this means using methods such as selective felling and thinning based on the concept of stand basal area, as well as the sustainable management of ungulates and the control of invasive non-native species.

Pro Silva's approach maintains timber yield while enhancing biodiversity and ecosystem health. By allowing natural regeneration and promoting a diverse mix of tree species the organisation's forestry practices create resilient forests that can adapt to changing environmental conditions.

This not only supports sustainable timber production but also contributes to the ecological and social benefits of rewilding, such as enhanced carbon capture, reduced risk of catastrophic wildfire and increased recreational value.

Today, sustainable forestry practices are increasingly being employed across Europe. This shows that it is possible to balance productive forestry with the principles of rewilding, creating forests that are both economically viable and ecologically rich.

5 Grasslands

The European context

Like European forests, grasslands in Europe have also been significantly degraded.

Historically, Europe's grassland ecosystems were maintained by the ecological impact of large herbivores. Since the megafauna extinction at the end of the Pleistocene, extensive grazing by livestock has somewhat replaced this natural process.

But with the more recent decline of traditional farming and land abandonment, European grasslands and the rich biodiversity they support are increasingly threatened by encroachment, which means they are gradually turning into forests through vegetation succession.

Today, we have an opportunity to restore these vital ecosystems through rewilding, particularly through the reintroduction of free-roaming large herbivores like European bison and semi-wild bovines.

5.1 The need for natural grazing

Grazing is an essential natural process which maintains grasslands and prevents encroachment by shrubs and trees. Without grazing, grasslands can quickly become overgrown, losing their characteristic open structure and biodiversity. Low-intensity grazing by large herbivores such as cattle, horses, and bison helps to create dynamic mosaic landscapes that support a wide range of plant and animal species.

The low-intensity grazing should align with natural grazing principles. You can find out more about these in further reading.

Use the Next and Prev buttons below to learn more about how grazing animals play several important roles in grassland ecosystems.

Use the Next and Prev buttons below to view the illustrations and use the full-screen icon to enlarge the images.

5.2 Grassland case studies

Case study 1: Tarutino Steppe, Ukraine

Tarutino Steppe in Spring, Ukraine Credit: Deli Saavedra / Rewilding Europe.

In Ukraine, the rewilding of grasslands is taking place in areas such as the Tarutino Steppe, close to the Danube Delta. This is one of the largest preserved steppe fragments in Ukraine and has seen significant restoration efforts, including the reintroduction of grazing animals.

Species such as kulan (wild donkeys), deer, steppe marmots and susliks have been released to help maintain open grassland.

Herd of kulan in Tarutino steppe. Credit: Deli Saavedra / Rewilding Europe.

The impact of these herbivores on the landscape has led to the creation of more varied habitats, which support a diverse array of wildlife. It has also boosted seed dispersal, further enhancing plant diversity. Rewilding efforts on the Tarutino Steppe demonstrate how natural grazing can help to restore and maintain grassland ecosystems (Rewilding Europe, 2023).

Case study 2: Lika Plains, Croatia

Velebit Mountains from Lika Plains. Credit: Neil Aldridge / Rewilding Europe.

The Lika Plains are located near the Velebit Mountains of Croatia, a region known for its karst landscapes and rich biodiversity. Here, large herbivores such as semi-wild bovines and horses were reintroduced to prevent the encroachment of shrubs and trees (Rewilding Europe, 2020).

Tauros wallowing at Lika Plains. Credit: Daniel Allen / Rewilding Europe.

Through their interaction with the landscape these herbivores maintain a dynamic, semi-open mosaic of habitats that support a wide range of species, including birds, insects and small mammals. The Lika Plains are home to several endangered species, such as the European ground squirrel and corncrake, which benefit from open grassland habitats maintained by grazing.

6 Rewilding terrestrial landscapes: an integrated approach

Forests, scrublands, and grasslands each support a wide range of biodiversity. When rewilding, it is important to not only recognise how these habitats differ, but also how they complement each other in supporting nature and delivering benefits to people.

By considering these habitats together, rewilding efforts can create a mosaic of interconnected ecosystems that enhance biodiversity and ecological resilience.

6.1 Rewilding and human activities

The rewilding of terrestrial landscapes must take account of human activities and infrastructure. People live, work and play on dry land which means that rewilding efforts need to take account of other forms of land use like agriculture, roads, and cities.

Use the Next and Prev buttons below to learn about rewilding and human land use and use the full-screen icon to enlarge the images.

7 The benefits of terrestrial rewilding

The rewilding of terrestrial landscapes can deliver a wide range of ecological, social and economic benefits.

Sundowner hike during gathering in Pettorano Sul Gizio Credit: Nelleke de Weerd / Rewilding Europe.

|

7.1 Challenges and solutions

Promoting rewilding and scaling it up alongside existing land uses can be challenging.

Click on each item in the list below to learn more about some example solutions:

7.2 Monitoring and evaluation

Effective monitoring and evaluation are necessary to assess the impacts of rewilding and adapt management strategies.

In Module 2, you learned about measuring ecological integrity using the Rewilding Score. The Rewilding Score provides an excellent overview of the condition of an area that can be replicated over time and compared to areas outside a rewilding landscape.

Rewilders often supplement the Rewilding Score with more specific monitoring for ecological changes and socio-economic impacts, using a wide variety of tools and technologies.

|

8 Coexistence

In Module 2, you learned about the rewilding principles, and how nature recovery can generate both challenges and opportunities. In this section, we dive deeper into what applying the rewilding principles means when we focus on people and wild nature living together.

We will focus particularly on the return of wildlife, although the same approaches are relevant to the return of natural processes that don't inherently involve animals, such as flooding, erosion, and natural forest regeneration.

8.1 Wildlife comeback in Europe – enabling coexistence

After centuries where the eradication of wild animals was both accepted and, in many cases, encouraged, the populations of some European wildlife species have grown both in size and geographical range over the last 40 to 50 years.

Today, mammals such as the Eurasian beaver, grey seal, and European bison are making a strong comeback, while bird species such as the barnacle goose, griffon vulture, great white egret, and Dalmatian pelican are also recovering well.

Reasons for upward population trends include legal protection through the EU Birds and Habitats Directives, changes in policy and land use, as well as species management and conservation efforts, including rewilding.

Griffon vulture, Gyps fulvus, Madzharovo, Eastern Rhodope mountains, Bulgaria. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

As populations of some European wildlife species recover, people are learning to live alongside them again. In some cases, this has led to challenges around coexistence, particularly in places where wildlife recovery has an impact on land use.

This includes, for example, beavers flooding land, livestock being predated by large carnivores, and the spread of diseases such as African swine fever. Fostering a growing acceptance and appreciation of wildlife is essential to any coexistence approach.

As you learned in Module 2, most human–wildlife coexistence issues are underpinned by different human perspectives on how and whether humans should share space and resources with wildlife again, the relative risks of wildlife to different interest groups, and the cultural values that different species reinforce or challenge.

Because there are multiple ways people see wilder nature, there must be different ways to help people live harmoniously with wildlife.

Physical efforts to prevent coexistence issues

Historically, efforts to promote human-wildlife coexistence have focused on using physical infrastructure to keep wildlife and human assets apart.

Click on each icon below to see some of the common methods that are used.

Working together

These physical measures on their own are often not enough to enhance coexistence to a necessary level. Living with wildlife is an emotional issue, it is not only a practical and financial one. Once damage caused by wildlife has taken place, the negative emotions this evokes are already in effect – compensation may be too slow or not enough to lessen these feelings.

Demonstrating the tangible benefits of wildlife comeback, and connecting people with wildlife in a positive, long-lasting way, have therefore become increasingly important, particularly in communities impacted by wildlife comeback.

International vulture awareness day 2023, Madzharovo, Bulgaria. Credit: Ivo Danchev / Rewilding Rhodopes.

Rewilding adopts a holistic approach to promoting coexistence with nature. This approach has a bottom-up focus, encouraging and enabling people to live alongside wild nature once again.

Physical measures to coexist with wilder nature are used in combination with:

- Building engagement, through positive communications, education, and inspiration, as you learned in Module 3.

- Developing nature-based economic activities in order to increase the economic value of wildlife for communities and therefore encourage acceptance, which you learned about in Module 4.

8.2 Managing success

The successful recovery of nature in Europe will mean an increase in wildlife populations. This is a cause for celebration for many reasons and can generate a wide range of benefits and new opportunities.

It will also pose challenges, which may influence people's behaviour and the way landscapes and seascapes are managed and used.

Human responses to such challenges can lead to behaviours that harm wildlife, such as causing habitat damage and disturbance. They may lead to more extreme actions such as retaliatory killings through shooting or poisoning, or misinformation campaigns against wildlife.

Wild Italian wolf, walking in the snow, in the Central Apennines. Credit: Bruno D´Amicis / Rewilding Europe.

The return of wildlife in some areas of Europe has already prompted a pushback against some species. The response to the increase in wolf numbers and geographical range in Europe is a striking example of this. Despite no recorded fatal wolf attacks on humans over the past 40 years and manageable losses to livestock (European Commission, 2023), the wolf has nonetheless become symbolic for those that oppose environmental protection.

Resistance to wolf comeback includes calls to downgrade its protected status with serious potential repercussions for wolves and many other species in future.

To enable wildlife comeback and nature recovery in Europe, we must proactively promote coexistence. To do this, we need to work with people to understand their fears and challenges, and find ways to address them in a constructive and collaborative way.

Different human perspectives

Most human–wildlife coexistence issues are underpinned by different human perspectives on how and whether humans should share space and resources with wildlife again, the relative risks of wildlife to different interest groups, and the cultural values that different species reinforce or challenge (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2023).

For instance, farmers might resent the return of predators like wolves or bears, fearing for their livestock and safety. People may also fear that removing dams and embankments will change the flow of a river and put their homes and property at risk from flooding.

At the heart of these issues lie differing perceptions of the value of wildlife, fears for livelihoods, and different priorities regarding land use and conservation.

Left unaddressed, these issues can escalate, leading to strained relationships, lawsuits, loss of livelihoods, and even violence between people, as well as against wildlife.

Coexistence Festival. Credit: Io Non Ho Paura Del Lupo.

To prevent these situations from arising, coexistence strategies must be developed through collaborative approaches, while respecting legal regulations and laws. Such approaches bring people together to share their needs and experiences, and plan, implement, and govern strategies to meet those needs.

In this way, the people living with wildlife can agree together who should benefit from prevention measures (such as electric fences and guardian dogs), what to do if problems still occur, and who is responsible for responding and overseeing this.

In Europe, there are countless examples where this has been done in a successful way – in some cases, for centuries.

8.3 The importance of local governance

National governments in Europe have a responsibility to ensure adequate enforcement systems to deter illegal activities such as poaching and habitat destruction. They may also offer compensation schemes for those that suffer the most severe losses as a result of living with wilder nature.

Complementary to this overarching enforcement and compensation role, community-based governance can be instrumental in fostering cooperation and preventing and mitigating coexistence issues.

Community-based governance usually involves bringing together local community members including landowners, farmers, hunters, fishermen, local business owners, NGOs, local government representatives (e.g. at the municipal level), and technical advisors (e.g. from agencies in charge of wildlife or agriculture).

Shepherd leading his sheep to a paddock. Southern Carpathians, Munții Ṭarcu, Caraș-Severin, Romania. Credit: Florian Möllers / Wild Wonders of Europe.

Together, they form a representative group that can share and analyse information, make decisions, help enforce those decisions (within an existing set of regulations), and resolve issues. They ideally work in line with a framework of transparent processes and principles that have been agreed in advance and in compliance with legal requirements.

Collaborative management approaches such as this empower local communities to identify, plan for, and mitigate current and potential coexistence issues, and can help those that are most exposed or vulnerable to find the necessary emotional, technical, and financial support.

This process brings diverse local interests in line with rewilding efforts, increasing cooperation and reducing fears and misunderstandings that can lead to coexistence challenges.

8.4 Case study: What does working with others and knowledge exchange look like in practice?

Bear-smart communities

Today, the Rewilding Apennines team and local partners are working hard to protect and enhance the endangered population of Marsican brown bears living in the Central Apennine mountains in Italy. The team are developing a network of large-scale wildlife corridors, enabling bears – and a wide range of other wildlife species – to move safely between protected areas.

In and around these wildlife corridors – which are focused on the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park, Sirente-Velino Regional Nature Park, and Gran Sasso and Laga Mountains National Park – the team are establishing a network of ‘Bear-Smart Communities’.

Wild European brown bear, solitary female peering from behind dwarf pines in mountain meadow. Western Tatras, Slovakia.

The Bear-Smart Community model, originally developed in British Columbia (Get Bear Smart, n.d.), employs various measures to help residents and businesses coexist with bears.

Click on each of the icons below to learn more about what these measures include:

Decisions on which measures to employ are made in consultation with community stakeholders and incorporated into coexistence plans overseen by community members. Benefit-sharing mechanisms may also be included.

In Pettorano sul Gizio, the first Bear-Smart Community in the Central Apennines, the team worked with a local NGO, authorities, and protected area managers. They used geo-spatial analysis to identify interaction areas and improve surrounding forests for bears. They also analysed local attitudes towards bears to prepare educational materials and guide community meetings.

The village of Pettorano sul Gizio, the first Bear Smart Community in the Central Apennines, Italy. Credit: Nelleke de Weerd / Rewilding Europe.

First information panel placed in light of LIFE Bear-Smart Corridors for the bear-smart community Genzana. Credit: Nelleke de Weerd / Rewilding Europe.

Following this period of assessment and dialogue, it was decided that the following coexistence measures would be employed:

- Modifying pools and tanks where bears could drown.

- Enhancing habitat – for example, by clearing scrub away from fruit trees in former orchards, in order to provide food for bears and divert them away from orchards under cultivation.

- Distributing damage prevention equipment, such as solar-powered electric fences, to enable people to protect beehives and other property.

- Replacing old rubbish bins with bear-proof bins to stop bears being attracted to waste.

- Developing rapid intervention teams, which local people could call if a bear was present in their area.

The Rewilding Apennines team also work with local businesses to explore new opportunities for nature-based tourism and help producers using bear-smart approaches benefit from a unified marketing strategy.

All these measures are brought together under the umbrella of a Bear-Smart Community that is chaired by the local mayor. A ‘bear conservation fund’ has also been set up to help finance expenses related to coexistence measures.

The impact of a Bear-Smart Community

After two years of work, in Pettorano sul Gizio and 15 other small towns across the Central Apennines, the Bear-Smart Community approach has:

- Enhanced 500 hectares of habitat, with greater availability of food for bears, in the corridors between the protected areas.

- Reduced by 30% bear damage to farm property and assets. For beehives, the reduction in damage was over 90%.

- Secured 21 pools to prevent bears from drowning.

- Enhanced public knowledge of monitoring, management, and human–bear coexistence.

- Developed at least one bear-related tourist package in each community.

Benefits to the economy

Working with local people to enable peaceful coexistence with bears has benefitted the local economy. People coming to see, monitor, or learn about the bears has meant extra business for hotels and hostels, restaurants, transport providers, and tour guides.

The Marsican brown bear has become a flagship species for the region and a valuable nature-based tourism asset. This is reflected in many different ways, from branded local products and statues to public bear-watching viewpoints and the names of local pubs.

Bear advocate Matteo Simonicca from Lecce nei Marsi in his ‘Bear Pub’. Central Apennines, Abruzzo, Italy. Credit Bruno D’Amicis / Rewilding Europe.

A replicable model

This model can be applied to more than one species. Although we began by focusing on bears, the same approach could be used for multiple species at once. Wildlife-smart communities have huge potential across Europe and need to be part of our rewilding plans. As European wildlife populations recover, encouraging and empowering people to live alongside them can generate wide-ranging benefits for communities and businesses, as well as generate additional support for further nature recovery.

‘I like to think of it as a positive feedback loop,’ says Rewilding Apennines team leader Mario Cipollone. ‘As more people here get behind rewilding, the more quickly nature can recover, which enhances the benefits it can provide to local communities. People in our communities then become even more supportive of rewilding and passionate about and proud of the nature around them. Pettorano sul Gizio is a prime example of how this cyclical process can work.’

‘We are now hosting many rewilding events,’ says Milena Ciccolella, owner of Il Torchio restaurant in Pettorano sul Gizio. ‘These have been a real lifesaver in economic terms, and have stimulated us creatively, as we now offer vegetarian dishes on our daily menu. We are also planning to offer cooking courses to ‘rewilding guests’.’

If you would like to dive deeper into this topic, here are some further resources you might be interested in:

- More detailed overview.

- Information on bear-smart produce.

- Useful video for context (first four minutes).

The work in Italy was funded by the EU LIFE Programme.

8.5 Building trust and confidence

As exemplified by the Bear-Smart Community approach, facilitating the exchange of knowledge and opinions can help to build mutual understanding and trust.

As you have learned, coexistence issues are often caused by a lack of information and different human perspectives of the value of wild nature. Enhancing understanding through engagement can help to promote coexistence between humans and wildlife.

This dialogue is not a one-off at the beginning of a rewilding initiative. Rewilding aims for wilder nature and a change in how wilder nature is understood and appreciated. As the relationship between people and nature changes over time, new ideas, opportunities, and challenges will emerge over time as well. Genuine partnerships, trust, collaboration, knowledge exchange, dialogue, and celebration of success should continue over time too.

When there are knowledgeable and skilled people present in a rewilding area, ready to respond and provide a helping hand in relation to coexistence issues, this can go a long way to building and maintaining trust and generating acceptance.

9 Module summary

In this module, you have learned about the changing land use patterns in Europe and that rewilding can offer a new path forward for nature and people in places experiencing land abandonment.

You have learned that few forests in Europe are truly natural, but that there are ways to move them to a more natural state, through artificially aging trees, leading deadwood in forests, and bringing back wild animals that interact with vegetation in many different ways.

You have also learned about grasslands, and how natural grazing is essential to keep some areas open. Grazers create a mosaic habitat, where grasses, scrub and woody plants all exist, interact and are needed when we are thinking at the scale of ecosystems and landscapes.

Wilder terrestrial habitats offer benefits to people, from capturing carbon, to offering new wildlife watching tourism opportunities. Yet they can come with challenges, as the land is where most human activities also take place.

For this reason, promoting coexistence is essential, and you have learned about a community-led approach that can bring stakeholders together and find new ways for people to thrive alongside wilder nature.

![]()

Now that you have completed this module, you should be able to:

- Determine what rewilding principles are most relevant and suitable to rewilding terrestrial landscapes.

- Explain the ecological, social, climatic, and economic importance of forests and grasslands ecosystems.

- Assess the impacts of key threats to terrestrial ecosystems, and how they disrupt natural processes.

- Compare the differences and similarities between rewilding in grasslands and in wooded areas, and their connections to each other and the wider landscape.

- Evaluate the role of keystone species and natural processes in maintaining healthy terrestrial ecosystems.

- Analyse case studies of rewilding forests and grasslands in Europe.

- Articulate the challenges and opportunities associated with wildlife comeback and select appropriate locally led positive coexistence measures.

|

9.1 Further reading

- Rewilding Europe (2015). Natural grazing – Practices in the rewilding of cattle and horses. Available at: https://www.rewildingeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Natural-grazing-%E2%80%93-Practices-in-the-rewilding-of-cattle-and-horses.pdf (Accessed: January 26, 2025).

- Publications Office of the European Union (2019) ‘The situation of the wolf (canis lupus) in the European union’ [Online]. Available at: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5d017e4e-9efc-11ee-b164-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-299076073 (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

- European Parliament (2020). The Rewilding of Europe: Policy options. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2020/641556/EPRS_ATA(2020)641556_EN.pdf (Accessed: January 26, 2025).

- von Korff, Y. (2024): A Practical Guide to Group Facilitation. The Threefold Approach. Routledge.

- Araújo, Miguel B. et al.(2024) Current Biology, Volume 34, Issue 17, 3931 - 3940.e5 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.07.045

- IUCN SSC (2020) IUCN SSC Position Statement on the Management of Human-Wildlife Conflict. Available at: https://iucn.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/2021-position-statement-management-hwc_en.pdf. (Accessed: 25 January 2025).

9.2 Module 5 quiz

Now it’s time to complete the Module 5 quiz – it’s a great way to check your understanding of the course content.

This quiz contains 5 questions and a pass mark of 60% and above is required if you'd like to be awarded your Module 5 – Terrestrial rewilding digital badge.

You can review the answers you gave, and which were correct/incorrect, after each attempt has been completed.

If you don’t pass the quiz at the first attempt, you are allowed as many attempts as you need to pass.