Freshwater rewilding

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Introduction to Rewilding |

| Book: | Freshwater rewilding |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 2:45 AM |

Table of contents

- Introduction

- 1 Rivers

- 1.1 Human impacts on rivers

- 1.2 Towards wilder waters

- 1.3 Case study: rewilding the Abramsån in Sweden's Nordic Taiga

- 1.4 Case study: giving the Waal River room in the Netherlands

- 1.5 Breaking barriers

- 1.6 Case study: breathing new life into the Danube Delta

- 1.7 Reintroducing wildlife

- 1.8 Case study: releasing crayfish in the Central Apennines

- 1.9 Rewilding riverbanks

- 1.10 Other initiatives

- 1.11 The impact of the land on rivers

- 2 Wetlands

- 3 Peatlands: an essential type of wetland

- 4 Carbon credits: supporting land use change

- 5 Module summary

Introduction

Freshwater systems underpin life on land. They provide clean drinking water and habitat for fish and other aquatic species, store huge amounts of carbon and offer places for recreation.

Despite their critical importance, many of Europe's freshwater ecosystems have been heavily degraded by human activities, such as drainage for agriculture, dam construction, channelisation, and industrialisation.

These activities have disrupted natural processes, damaged habitats, negatively impacted biodiversity and impaired the way ecosystems function. This has undermined many of the benefits these systems deliver to people and nature.

In this module you will learn about why freshwater systems need rewilding and the benefits this delivers, as well as some of the various approaches to rewilding rivers, wetlands and peatlands.

![]() Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

After completing this module, you should be able to:

- Identify which rewilding principles are most applicable to rewilding freshwater landscapes.

- Explain the ecological, social, climatic and economic importance of freshwater ecosystems.

- Assess the impacts of key threats to freshwater ecosystems and how they disrupt natural processes.

- Compare the differences and similarities between river and wetland rewilding and the connection to the surrounding landscape.

- Evaluate the role of keystone species and natural processes in maintaining healthy freshwater ecosystems.

- Analyse case studies of freshwater rewilding in Europe.

1 Rivers

People have interacted with and depended on rivers for millennia.

In industrial times rivers were widely used for transport and to power mills and factories. This saw many waterways choked by dams and other artificial barriers and straightened to facilitate the transport of goods and people.

While many of these barriers and other interventions are now obsolete, they continue to have a hugely negative impact on fish, other wildlife and people.

1.1 Human impacts on rivers

Eurasian otter, Lutra lutra, Pusztaszer reserve, Hungary. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Wild Wonders.

Today, freshwater systems are also impacted by ongoing human activities. Water may be removed from rivers for irrigation, or added to them as wetlands and forests are drained. These removals and additions influence the chemical composition, speed and flow of river water, altering habitats, sedimentation and flood patterns.

The majority of European rivers are now in poor health, with only a few truly wild stretches remaining. The result has been a huge reduction in biodiversity and water quality accompanied by a widespread deepening of riverbeds and a massive loss of floodplains and wetlands.

In many cases, European rivers have been altered so much that we no longer know what wild water looks like. With climate change bringing new challenges we urgently need a new relationship with water – accepting it into our landscapes again and rewilding it where we can.

1.2 Towards wilder waters

Rivers harbour some of the richest biodiversity on earth and provide an array of benefits to people. Healthy, free-flowing rivers that are well-connected with surrounding landscapes offer a wide range of habitats for wildlife species. Such ‘waterscapes’ also help to purify water and reduce the risk of downstream flooding in times of heavy rainfall, and are more resilient to the effects of climate change.

Rewilding means letting nature recover itself. In the context of rivers this means giving them the space and freedom to flow, flood, freeze and even periodically dry out. This means:

- removing artificial structures such as man-made dams, embankments and weirs

- reconnecting rivers to their floodplains, allowing riparian vegetation to naturally regenerate

- supporting the return of wildlife such as water voles, beavers, otters, and aquatic birds.

Some rivers may need a helping hand at first but many can heal themselves, often quickly and effectively.

Click or hover your cursor over each picture to enlarge it.

Healthy rivers are free-flowing rivers with more space for dynamic, natural processes such as the free flow of water and flooding.

1.3 Case study: rewilding the Abramsån in Sweden's Nordic Taiga

In the Nordic Taiga most rivers have been severely damaged by historical logging. Here, Rewilding Sweden is working to restore natural water courses and forests. In 2023 and 2024, the Rewilding Sweden team led efforts to rewild a stretch of the Abramsån River in the valley of the Råne River by removing embankments, removing log flooring and adding gravel and silt. These actions will help to create a range of different habitats, slow down the flow of water, promote sedimentation and increase connectivity between the river and the surrounding forests (Rewilding Europe, 2023c).

Rewilding rivers helps to retain water in the freshwater system for longer. In the case of the Abramsån, this has a huge ecological benefit for:

- insects, birds, and fish that depend directly on the river

- natural grazers like reindeer who feed on hanging lichens that thrive in moist forest conditions, and moose that graze on plants in and around rivers.

In addition, seeds from upstream can be deposited on the river floodplain, boosting biodiversity in flooded areas. Deadwood, washed down the river, can also be deposited which provides an important substrate for macrofauna, creating a wide range of micro-habitats and adding nutrients to the soil.

Use the left and right arrows below to show the before and after landscape.

1.4 Case study: giving the Waal River room in the Netherlands

The narrow watershed of the Waal River used to create a bottleneck in the Dutch city of Nijmegen, which has long been prone to flooding. Severe flooding in 1993 and 1995 in the Netherlands led to a change in the way rivers and flood risk were managed across the country.

Whereas previous policy was based on enhancing flood protection through the construction of higher dykes, new policy supported the creation of more space for rivers - by reconnecting floodplains, recovering former side channels, and moving dykes further from river channels. This national programme was named "Room for the River".

In Nijmegen, the city chose to embrace this new approach and make space for the Waal. By restoring the riverscape to a more natural condition, the aim was to help manage water flow in a better way, and thereby prevent flooding to nearby homes and businesses. In 2012, efforts were begun to remove infrastructure and houses. The river's main dyke was moved 350 metres back from the edge of the water, while an extensive new river channel was dug parallel to the existing one. To cross this new channel, the Waal Bridge was extended and three new bridges were constructed.

Costs and benefits

While the cost of the work on the Waal exceeded 350 million euros, there were four main benefits:

Click on each of the icons below to explore each benefit.

All information in this case study is from Climate ADAPT (2016).

The Waal River in Nijmegen was transformed through the 'Room for the River' programme, reducing flood levels by 35 cm and creating a new nature reserve. Credit: Richard Brunsveld / Unsplash.

1.5 Breaking barriers

The momentum behind dam removal in Europe continues to increase, with more than 6000 people now playing a pivotal role raising awareness and driving action across the continent through the coalition.

The removal of dams has already proven to be one of the most efficient and cost-effective ways of restoring rivers. This is why Dam Removal Europe – a growing European-wide coalition of organisations – is working to restore European rivers by removing old and obsolete dams and weirs.

The momentum behind dam removal in Europe continues to increase, with more than 6000 people now playing a pivotal role raising awareness and driving action across the continent through the coalition (Dam Removal Europe, 2023a).

According to the Dam Removal Europe report published in 2024, a remarkable 487 barriers were removed across 15 European countries in 2023 – a 50% increase on the year before. These initiatives helped to restore over 4300 kilometres of free-flowing rivers.

|

1.6 Case study: breathing new life into the Danube Delta

Several years ago, the Rewilding Ukraine team and local partners kicked off long-term efforts to restore natural water flow and connectivity in the Danube Delta rewilding landscape, which is divided between Ukraine, Romania and Moldova.

Large-scale hydro-engineering work carried out in the Ukrainian part of the delta during the twentieth century – which primarily involved the creation of an extensive network of canals and dykes, and agricultural polders – had a hugely negative impact. Effects include:

- leaving stagnating water bodies

- altering sedimentation patterns

- disconnecting floodplains

- devastating populations of fish and other wildlife

- diminishing the ability of the delta to recycle nutrients.

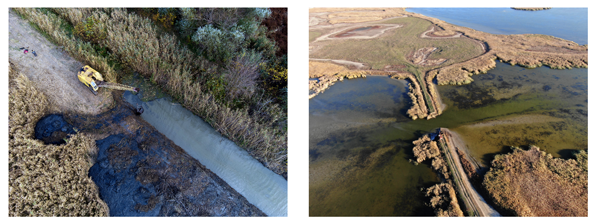

By removing dykes and dams and reconnecting channels, rewilding efforts are breathing new life into the delta and its communities (Rewilding Europe, 2025).

Cleaning of channels between the Danube River and Katlabuh Lake helps to restore water flow. Credit: Andrey Nekrasov [left]. Dam removal in the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta in 2019. Credit: Maxim Yakovlev [right].

|

1.7 Reintroducing wildlife

The reintroduction of keystone species can be an important component of rewilding rivers and wetlands in Europe, helping to restore natural ecosystems and enhance biodiversity. Beavers are known as ecosystem engineers, with their dam-building activity creating wetlands that support a variety of plant and animal life. These wetlands can improve water quality, reduce flood risks, and provide habitats for numerous other wildlife species.

The reintroduction of sturgeon, another keystone species, helps maintain the ecological balance of river systems by contributing to nutrient cycling and providing prey for other wildlife. Crayfish, as both predators and prey, play a significant role in maintaining the health of aquatic ecosystems by controlling algae and detritus levels, which in turn supports a diverse range of other aquatic life.

In Europe, the rewilding of rivers through species reintroductions can have socio-economic as well as ecological benefits. Restored river ecosystems can boost local economies by enhancing opportunities for nature-based tourism and recreational activities like fishing and birdwatching.

|

1.8 Case study: releasing crayfish in the Central Apennines

The Rewilding Apennines team have been releasing white-clawed crayfish in the Central Apennines rewilding landscape in Italy since 2023, following a positive feasibility study carried out in 2020 (Rewilding Europe, 2020). Two breeding centres are now operational, with one more in the pipeline.

The white-clawed crayfish, which is found in freshwater ecosystems from the Balkans to Spain, and as far north as the UK, is considered a keystone species. It is an important food source for animals such as otters, fish and birds, while it helps to maintain balance within invertebrate communities as it predates on smaller animals. It also helps to keep water bodies clean by feeding on decaying matter. Sadly, it is in decline across much of its range, facing an array of threats including poaching, disease, competition with invasive species, and climate change (Rewilding Europe, 2023a).

Click on the left-hand and right-hand images to view all the pictures.

1.9 Rewilding riverbanks

Rewilding the banks of the rivers is also an important aspect of rewilding rivers as it helps to re-establish the natural processes and biodiversity that are essential for healthy aquatic ecosystems.

Riparian zones are the areas adjacent to rivers and streams and they are important areas in rewilding. Riparian vegetation supports a diverse array of wildlife, offering food and shelter to birds, insects and mammals. The roots of riparian plants help to stabilise soil and reduce the impact of floods, while their foliage provides shade that keeps water temperatures suitable for aquatic life.

Measures to rewild riverbanks include allowing natural regeneration to occur and leaving fallen deadwood lying in rivers. Flood waters can deposit seeds, dead leaves and wood from upstream, enriching the soils with nutrients and bringing new species to the area. As with the forests and grasslands you learned about in Module 5, grazing, trampling and browsing are important here too as they also disperse seeds and create and maintain a diverse mosaic habitat.

River wood pasture. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

Click here for an enlarged version of the above image.

River (riparian) wood debris and their role. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

Click here for an enlarged version of the above image.

The water buffalo: A Keystone species. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

1.10 Other initiatives

In Europe, a wide range of initiatives promote river rewilding as way of restoring natural ecosystems and enhancing biodiversity. The Living Rivers Europe (n.d.) coalition, led by WWF and other environmental organisations, focuses on advocating for the implementation and enforcement of the EU Water Framework Directive. This initiative aims to protect and restore freshwater ecosystems by addressing issues such as unsustainable agriculture, hydropower and flood defence.

Another important project is SmartRivers, managed by WildFish, which employs citizen science to monitor river health through invertebrate sampling. This helps fill the gap in national monitoring efforts, providing valuable data on water quality and biodiversity that can drive local and national conservation actions. Both initiatives highlight the importance of community involvement and scientific research in achieving sustainable river management and rewilding goals (Wildfish, n.d.).

1.11 The impact of the land on rivers

Freshwater systems are the arteries and capillaries of terrestrial landscapes. As such, ecological conditions on land, and the way land is used, can have a significant impact on rivers. Consider the flow of sediments, nutrients and seeds, for example. Land use can play a major role in determining the health of river systems – the agricultural runoff of fertilisers, pesticides, and other chemicals can have a very detrimental impact on riverine conditions and biodiversity.

The more natural the land use in a river catchment or alongside a river is, the more this benefits the water in the river and wild nature associated with it.

Two important impacts for the land to the water are the impact of chemicals running into the river from the land and the removal of deadwood from the riverbanks.

Click on each list item below to learn more about the impact of chemical runoff:

The impact of deadwood in rivers:

Rewilding efforts that incorporate these practices help to restore natural processes and improve the health of rivers, leading to revitalised and resilient waterscapes.

2 Wetlands

Wetlands are areas where water covers the soil and is present at or near the surface for varying periods of time during the year.

They include marshes, swamps, bogs and fens, each of which have their unique characteristics and species.

2.1 The importance of wetlands

Wetlands are critically important for several reasons.

Click on or hover over each numbered hotspot on the image below to learn more.

2.2 Challenges facing wetlands

In 1971 the International Convention on Wetlands was adopted in Ramsar, Iran, pledging to protect wetlands. Despite this global recognition more than 50 years ago they continue to be extensively altered and degraded by human activities (Ramsar Convention Secretariat, n.d.).

Research indicates that 3.4 million km2 of inland wetlands - representing 21% of the entire global wetland area - have been lost since 1700. This loss, which has accelerated from the start of the twentieth century, has been concentrated in Europe, the United States, and China.

Click on each list item below to find out more about the main drivers of wetland loss:

2.3 Principles of wetland rewilding

As with all rewilding the main focus in wetland rewilding is to create a situation where natural processes can lead nature’s recovery. Often this involves removing the human footprint from the landscape and undoing the harm that people have done, then stepping back to let nature lead.

For wetlands this means restoring natural hydrology to re-establish natural water regimes. This can be achieved by removing drainage systems or other human infrastructure that artificially separate bodies of water. This allows more natural water flow and dynamics to resume, with knock-on impacts on:

- sedimentation

- water nutrients

- vegetation

- nursery and feeding grounds for fish species and birds.

Where wetlands have become too disconnected from wider natural habitats for natural recolonisation, or species have become locally extinct due to overfishing, hunting and persecution, wildlife reintroductions may be needed to restore these species to the wider wetland ecosystem.

2.4 Methods of wetland rewilding

Some of the most important methods of wetland rewilding include:

- Plugging drainage ditches:

- Description – Blocking drainage ditches (e.g. putting back soil) to restore natural water levels and hydrological processes.

- Example – In the Oder Delta, which you will read more about in the peatlands case study later in this module.

- Impact – Improved water retention, restored wetland habitats, and increased wilder nature, including wild species.

- Reintroducing keystone species:

- Description – Reintroducing species that play a critical role in maintaining ecosystem health.

- Example – The reintroduction of beavers in various European wetlands, which create ponds, slow water flow, and increase habitat complexity.

- Impact – Enhanced biodiversity, improved water quality, and natural flood management.

The beaver: A keystone species. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

2.5 Case study: The Danube Delta

In 2023, 20 fallow deer and 20 red deer were released on Bilgorodskiy Island in the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta by Rewilding Ukraine and the Danube Biosphere Reserve.

Deer have an important role in:

- disbursing seeds across the landscape

- consuming vegetation that could otherwise dominate the wetlands

- attracting predators to the area, helping to restore natural predator–prey interactions.

|

Situated in Ukraine, Romania and Moldova, the Danube Delta is Europe’s largest remaining natural wetland, extending across more than 650,000 hectares. Boasting the world's largest reedbeds, this unique ecosystem of unaltered rivers, lakes, marshes, steppes, dunes, lagoons, and old-growth forests is home to more than 60 species of fish, including four species of sturgeon, and mammals such as otters and the European mink.

The delta supports colonies of breeding birds totalling tens of thousands of individuals – notably terns, white pelicans and herons – and colonies of several globally threatened species are found here. Most of the world's global pygmy cormorant population is found in the delta, as is most of the Dalmatian pelican population in Europe.

Context and opportunity

Despite the transboundary Danube Delta being the largest and most natural delta in Europe, widespread development of infrastructure during the twentieth century led to a deterioration of natural flood dynamics and the filtering function of the area's reed marshes. It also caused salinisation and biodiversity loss.

Attempts to control natural river dynamics by constructing polders, dams and dikes have negatively impacted local residents, particularly fishing communities (with a 60% decrease in fish stocks).

Much of the infrastructure that has caused these impacts is now dilapidated and obsolete.

Rewilding progress

Supported by Rewilding Europe, Rewilding Ukraine and Rewilding Romania have taken vital steps forward and restored large parts of the delta by significantly improving the ecological integrity and ecosystem functioning of 40,000 hectares of wetland and terrestrial (steppe) habitat.

Key natural processes, particularly flooding and natural grazing, are being re-established as driving landscape-forming processes. Fostering these processes is encouraging wildlife comeback, enhancing biodiversity and underpinning the development of local nature-based economies.

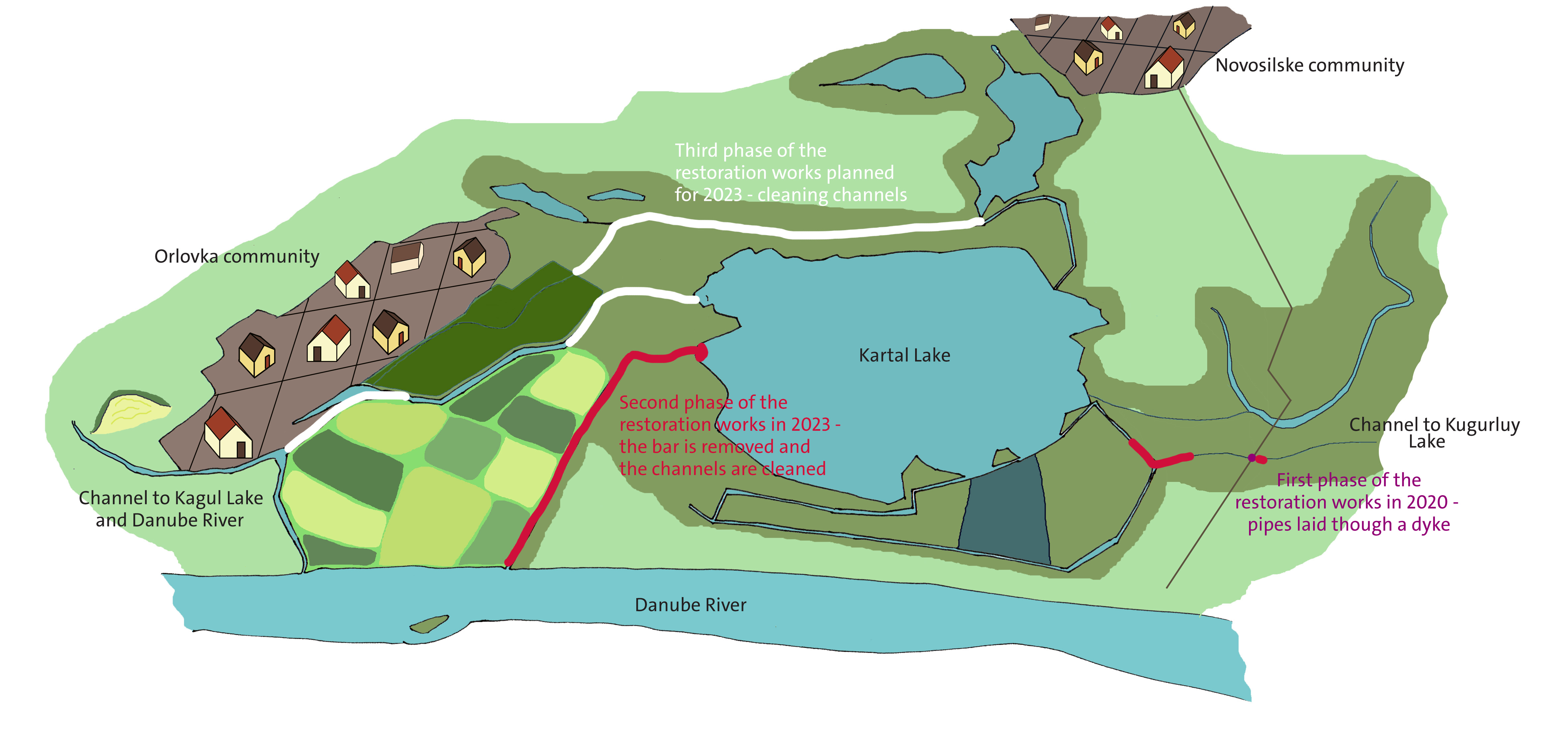

A map illustrating the restoration work currently being undertaken by Rewilding Ukraine and local partners.

The main rewilding interventions, mostly on the Ukrainian side, have so far been:

- Ten obsolete dams and obstacles have been removed on the Kogilnik, Kagach, and Sarata rivers to restore natural flow, spawning grounds and meadows.

- Ecological processes and natural hydrology have been restored on Ermakiv Island through the partial removal of dykes surrounding the island.

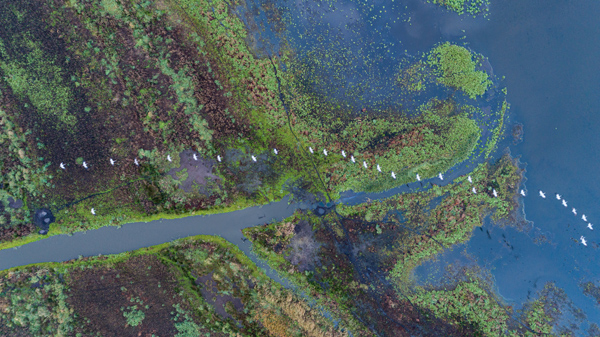

- Water quality has been improved, productive shallow wetlands restored and native fish species populations supported by improving the connectivity and water exchange between the Danube River and some large lakes, such as Katlabuh and Kartal.

- Over the last five years, dynamic natural processes in the delta have been revived by restoring natural grazing, with over 200 large herbivores released, including the red and fallow deer you saw in the film earlier. Others include water buffalo, konik and hucul horses and kulan.

- The growth of nature-based tourism has been supported through the construction of a wildlife hide and observation tower on Ermakiv Island, as well as information panels and other infrastructure on the Tarutino Steppe.

- Eco-ethno festivals held near Beleu Lake in the Republic of Moldova and in the Tarutino steppe in Ukraine have engaged local communities, reviving a sense of pride in their nature and culture.

- An education campaign has been launched in all three countries of the Danube Delta.

Cleaning of the channels between Danube river and Katlabuh lake. Credit: Andrey Nekrasov.

Helping pelican populations recover

The vulnerable Dalmatian pelican requires undisturbed, fish-filled waters with extensive flooded and shallow areas. Between the 1950s and 1980s, the construction of dykes and agricultural polders reduced suitable habitat for the birds and impacted heavily on local communities.

From late 2019 the Rewilding Ukraine team started to construct artificial nesting platforms to encourage the breeding of Dalmatian pelicans. At present these iconic birds lack safe and suitable locations in the delta to breed – this temporary measure will hopefully create suitable conditions for pelican reproduction, despite difficulties in monitoring due to the ongoing war.

With wetland rewilding efforts restoring natural processes and habitats in the delta the team is optimistic that new natural breeding sites will develop.

Restoring natural water flow in the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta will support the comeback of the Dalmatian pelican, one of this important wetland’s most iconic indicator species. Credit: Maxim Yakovlev / Rewilding Europe.

3 Peatlands: an essential type of wetland

Peatlands are a type of wetland landscape characterised by waterlogged soils made up of dead and decaying plant material.

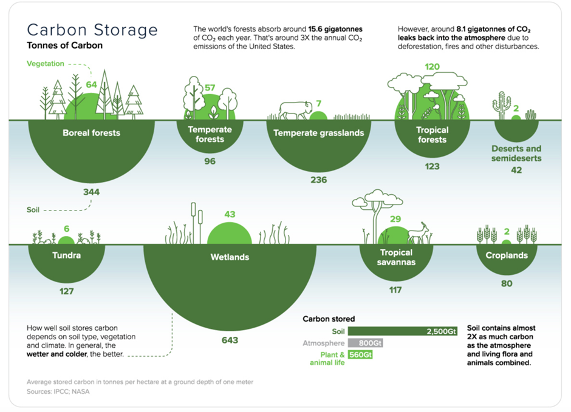

- Despite only covering around 3–4% of the planet’s land surface, peatlands contain up to one-third of the world’s soil carbon which is twice the amount of carbon found in the world’s forests.

- In addition to carbon storage, peatlands are unique and vital ecosystems with special flora and fauna that play a critical role in water regulation and biodiversity support.

- Peatlands occur in almost all European countries. More than half of these are degraded and used for agriculture, forestry and peat extraction. The EU alone is the world's second largest emitter of greenhouses gases (GHGs) from drained peatland.

Rewetted peat bogs and the Peene Rive, west of the city of Anklam, Rewilding Europe Oder Delta, Germany. Credit: Florian Möllers / Rewilding Europe.

3.1. Threats to peatlands

Peatlands face many of the same challenges that other forms of wetland do.

However, additional threats to peatlands includes the extraction of peat for use in horticulture and as a fuel source, which depletes peatland ecosystems and releases stored carbon into the atmosphere.

3.2 How do we rewild peatland?

Rewetting

Rewetting peatlands is a critical measure for restoring these vital ecosystems and mitigating the scale and impact of climate change.

Peatland rewetting involves raising the water table to restore the natural, waterlogged conditions of peatlands. This can be achieved by blocking drainage ditches and constructing ‘leaky’ dams with natural materials that are already present in the landscape like peat, other soils or vegetation. It is also important to ‘re-profile’ the peat. This means making the sides of drainage channels less steep to slow the flow of water over them, which reduces the rate of erosion.

These actions reduce the rate of water flow across the peatland area, thereby making the peat wetter and kick-starting the recovery process. The removal of forest plantations can also help to restore the water balance of peatlands as water is no longer taken up by their root systems. Removing plantations does not have to be done mechanically. If the peat is re-wetted the trees in permanent standing water will eventually die off naturally.

Reintroducing wildlife

Peatlands are important for a huge array of plant and animal species that are specially adapted for wet conditions. When peatlands are drained, populations of these species are negatively impacted and can even disappear.

When degraded peatlands are restored to wetlands again some of these species can return naturally if source populations are still located nearby, or seed banks are still available in the soil.

For other species the barriers to returning are often too great – this is particularly the case for vegetation and some invertebrates such as sphagnum and large marsh grasshoppers. In this case, reintroductions or translocations are needed to help them become re-established.

If you wish to know more about this particular topic once you have completed this module we recommend you watch the IUCN UK Peatland Programme video on reintroductions and translocations, in the context of peatland. You can find it in the further reading section.

3.3 Case study: rewilding the Oder Delta

The Oder Delta is a giant interconnected mosaic of rivers, lakes, wetlands, heathlands and riparian forests on the border between Germany and Poland. As tributaries of the Oder River, many smaller rivers and streams here are in poor ecological condition.

Riverbeds have been artificially straightened, deepened and embanked in many places, the free flow of water has been restricted by dams and weirs, and the areas surrounding rivers drained and reclaimed for agriculture and forestry.

Aerial view of European cranes flying over the marshland of Anklamer Stadtbruch, Rewilding Europe Oder Delta, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany. Credit: Florian Möllers / Rewilding Europe.

The Rewilding Oder Delta (2025) team are working to restore local waterways through a range of measures. These include:

- rewetting wetlands near rivers to increase water storage

- removing barriers to increase habitat connectivity

- supporting riverine species by restoring spawning grounds, which typically involves adding stone and gravel in locations where it should occur naturally.

The overall goals are to:

- Restore natural water flow.

- Enhance biodiversity.

- Increase connectivity.

- Restore fish migration.

- Boost the overall health, functionality, and resilience of the natural landscape.

In addition, the return of keystone wildlife species supports the development of local nature-based economies.

Click on each thumbnail below to enlarge the image.

4 Carbon credits: supporting land use change

As you learned in Module 4, different habitats can store different amounts of carbon. Wetlands are the most important carbon sinks of all habitat types. Wetlands, and particularly peatlands, represent an important opportunity for generating carbon credits that can help fund further rewilding.

A diagram illustrating carbon storage in the Earth's ecosystems. Carbon storage in such ecosystems is a vital component of the global carbon cycle. Credit: Carbon Streaming Corporation and Visual Capitalist.

Income from carbon credits generated by rewilding peatlands can become a source of income for landowners and managers. It represents an important financial incentive to change from intensive, environmentally harmful land management practice to a rewilding approach that benefits people, nature and climate.

4.1 The benefits of freshwater rewilding

As you have learned in the case studies of rivers, wetlands and peatlands, the range of benefits of rewilding are enormous.

Click on the images below to read more about each example.

|

5 Module summary

In this module you have learned about the importance of enabling fresh water to move naturally through landscapes. Most rivers in Europe are heavily modified with structures that would take millennia to degrade naturally, so removing dams, weirs, ditches and embankments is essential to kick-start natural hydrological processes.

Doing so can benefit people through reduced risk of downstream flooding by slowing the rate of flow and retaining more water upstream, which can help to counteract the impact of droughts. Wilder water also provides important income-generating and wellbeing benefits – the potential for new tourism and beautiful places for adventure, rest or relaxation.

You have also learned about the importance of wetlands for nature, people and climate. Wetlands have been extensively drained across Europe, mainly for agriculture and other human activities, while most European rivers are dammed or embanked.

Restoring natural water dynamics, creating free-flowing rivers and rewetting peatlands and grasslands – combined with the reintroduction and reinforcement of wildlife populations – are essential measures to help these critically important ecosystems recover, and to expand and enhance vital habitats for birds, fish, mammals and invertebrates.

You have learned about the wide range of benefits that healthy peatlands deliver to nature and people, how they store vast quantities of carbon, and how rewilding them can help to mitigate the scale and impact of climate change.

Through the case studies you have learned how committed people and organisations across Europe take practical action to rewild freshwater systems – from the north of Sweden and the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta, to the floodplains of the Waal near Nijmegen in the Netherlands and the transboundary Oder Delta.

![]()

Now that you have completed this module, you should be able to:

-

Identify which rewilding principles are most relevant and suitable to rewilding freshwater landscapes.

-

Explain the ecological, social, climatic and economic importance of freshwater ecosystems.

- Assess the impacts of key threats to freshwater ecosystems and how they disrupt natural processes.

-

Compare the differences and similarities between river and wetland rewilding and the connection to the surrounding landscape.

-

Evaluate the role of keystone species and natural processes in maintaining healthy freshwater ecosystems.

-

Analyse case studies of freshwater rewilding in Europe.

|

5.1 Further reading

- European Peatlands Initiative (n.d.) European Peatlands Initiative. Available at: https://europeanpeatlandsinitiative.com/ (Accessed: January 26, 2025).

- arkrewilding.nl (n.d.) 'Smart Rivers'. Available at: https://arkrewilding.nl/sites/default/files/media/Gelderse_Poort/Smart_Rivers_international.pdf (Accessed: January 26, 2025).

- Ramsar (n.d.) 'Global guidelines for peatland rewetting and restoration'. Available at: https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/rtr11_peatland_rewetting_restoration_e.pdf (Accessed: January 26, 2025).

- Günther, A., Barthelmes, A., Huth, V. et al. Prompt rewetting of drained peatlands reduces climate warming despite methane emissions. Nat Commun 11, 1644 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15499-z

- Process-based Principles for Restoring River Ecosystems (n.d.) Available at: [https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2010.60.3.7] (Accessed: January 26, 2025).

- Why Climate Change Makes Riparian Restoration More Important than Ever (n.d.) Available at: https://er.uwpress.org/content/wper/27/3/330.full.pdf (Accessed: January 26, 2025)

- YouTube (2024) Species reintroductions: from principles to practice webinar', IUCN UK Peatland Programme [Online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RkdT-RXuex4 (Accessed: January 26, 2025).

5.2 Module 6 quiz

Now it’s time to complete the Module 6 quiz to check your understanding of the course content.

This quiz contains five questions and a pass mark of 60% or above is required if you'd like to be awarded your Module 6 – Freshwater rewilding digital badge.

You can review the answers you gave and which were correct/incorrect after each attempt has been completed.

If you don’t pass the quiz at the first attempt you are allowed as many attempts as you need to pass.