Marine rewilding

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Introduction to Rewilding |

| Book: | Marine rewilding |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 2:46 AM |

Table of contents

- Introduction

- 1 Threats to marine environments

- 2 Towards healthier marine ecosystems

- 3 Marine rewilding vs terrestrial rewilding

- 4 Passive marine rewilding

- 5 Legal protection of species

- 6 Active rewilding in the sea

- 7 Working at seascape scale

- 8 Financing rewilding in the sea

- 9 Building engagement in a marine context

- 10 Module summary

Introduction

The ocean covers nearly three-quarters of the Earth's surface. It provides us with food, transport, recreation and supports the vital web of life that underpins our planet.

Critically, it is the source of around half the Earth's oxygen.

Sunset over the Adriatic Sea, Šljuka area. Credit: Nino Salkić.

Today, estuarine, coastal and marine environments face an array of mounting pressures but there is hope for the future. Rewilding can restore marine ecosystems and their natural processes, reversing decades of degradation caused by pollution, habitat loss, overfishing, destructive human activity and climate change. Through marine rewilding our oceans, seas, and coastal waters can flourish once again.

![]() Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

After completing this module, you should be able to:

- Determine what rewilding principles are most relevant and suitable to rewilding seascapes.

- Explain the ecological, social, climatic and economic importance of marine ecosystems.

- Assess the impacts of key threats to marine ecosystems and how they disrupt natural processes.

- Compare different approaches to rewilding within the marine environment.

- Evaluate the role of keystone species and natural processes in maintaining healthy marine ecosystems and assess how their restoration can enhance ecological balance.

- Analyse case studies of marine rewilding in Europe.

- Compare the similarities and differences between terrestrial and marine rewilding.

1 Threats to marine environments

In this first section you will consider the impact that global warming has on marine environments, the pressures on fishing and the effects of pollution and acidification on marine waters.

1.1 Climate change

Global warming impacts marine environments in many ways.

Rising temperatures cause ice to melt, adding water to the ocean. They also cause water to expand as it heats up. The resultant ongoing rise in sea level poses a threat to communities, river deltas, estuaries and coastal wetlands, agricultural and industrial land, and coastal urban areas.

Aerial view of a distributary channel of the Danube river flowing into the Black Sea, Danube Biosphere Reserve in Danube delta. Credit: Andrey Nekrasov.

Climate change is also causing many marine wildlife species to move to new parts of the ocean. As water temperatures rise, species found in the tropics and Mediterranean are beginning to appear further north in the Atlantic while some fish typically found in the Atlantic are moving to cooler northern latitudes.

The good news is that the ocean absorbs around a third of all the carbon dioxide emissions from human activities. Marine rewilding is therefore an important nature-based climate solution.

1.2 Fishing pressures

In 2018 it was estimated that nearly 90% of the world’s marine fish stocks were fully exploited, overexploited or depleted.

Overfishing is defined as too many fish being caught so there are not enough adults to breed and sustain a healthy population (Marine Stewardship Council, n.d.).

In addition to overfishing, certain methods of fishing have a greater negative impact than others. For example, trawling and dredging can damage sensitive seabed habitats.

Click on the icons below to reveal two more examples.

All of these pressures mean there is an urgent need to:

- rewild the sea and promote wild fish populations and marine and coastal habitats to recover

- enhance natural processes including those that help mitigate climate change

- support coastal communities.

1.3 Pollution

Pollutants in estuarine, coastal and marine waters can come from multiple sources. They can be washed from inland urban and agricultural areas into rivers, or come directly from boats and ships, coastal areas and industrial activities taking place at sea (e.g. oil and gas extraction, fish farms).

Chemicals, human sewage, nutrients from farms, and plastic and other debris can all have a significantly negative impact on marine life and coastal communities and visitors.

1.4 Acidification

The ever-increasing level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere means the ocean is now absorbing more carbon than ever before.

This changes the chemistry of marine water and results in it becoming more acidic. Ocean acidification can create conditions that eat away at the minerals used by oysters, clams, lobsters, shrimp, coral reefs, and other marine life to build their shells and skeletons. Human health is also a concern.

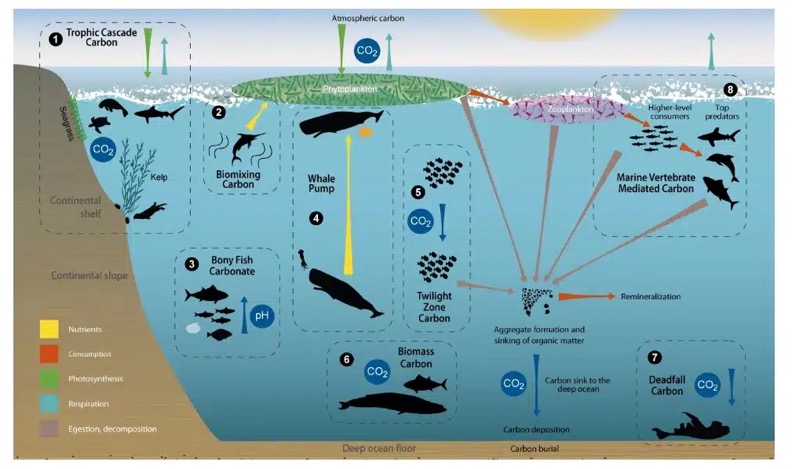

Marine life plays a crucial role in tackling climate change as summarised in Animating the Carbon Cycle, which shows the role wildlife plays in carbon uptake.

Example of Animating the Carbon Cycle in marine coastal and deep ocean ecosystems. Credit: Yale/GRA.

Click here for an enlarged version of the above image.

Whales contribute significantly by diving deep and bringing nutrients to the surface, which supports the growth of phytoplankton. These microscopic plants absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide during photosynthesis which helps to reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (Global Rewilding Alliance, 2024).

Marine rewilding efforts enhance these natural processes and by m aintaining healthy ecosystems, we can ensure that marine life continues to sequester carbon effectively and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

2 Towards healthier marine ecosystems

Coastal Waters in Croatia. Credit: Nino Salkic.

Just as in terrestrial rewilding, marine rewilding is about restoring natural processes. These processes can then revitalise ecosystems to the point where they can sustain themselves independently.

The same types of natural processes occur in the marine environment as on land.

Click on each icon to view some examples.

One of the key processes is the natural flow of water and sediments. In estuaries and deltas the movement of freshwater from rivers into the sea carries essential nutrients and sediments that support diverse habitats. Human interventions like damming and channelisation disrupt these flows (see Module 6), leading to habitat degradation which impacts the marine environment.

Another crucial process is the role of keystone species in maintaining ecosystem health. For example, in coastal areas, species like oysters and mangroves play significant roles in water filtration, sediment stabilisation and providing habitat for other organisms. Oysters filter large volumes of water, removing pollutants and improving water quality, while mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marsh plants protect shorelines from erosion and provide breeding grounds for fish.

Reintroducing and protecting these species can help restore the natural processes they support, leading to healthier and more resilient ecosystems.

Schools of multiple fish species seek protection in the lush reedbed of Danube Delta, Romania. Credit: Magnus Lundgren / Rewilding Europe.

Additionally, the natural cycling of nutrients is essential for marine ecosystems. In the open ocean, processes like upwelling bring nutrient-rich waters from the deep sea to the surface, supporting plankton blooms that form the base of the marine food web. Coastal and estuarine areas benefit from nutrient cycling through the decomposition of organic matter by microorganisms which releases nutrients back into the ecosystem.

Rewilding efforts can enhance these processes by protecting and restoring habitats that facilitate nutrient cycling like seagrass beds and salt marshes.

By focusing on these key natural processes rewilding can help restore the health and functionality of marine ecosystems.

3 Marine rewilding vs terrestrial rewilding

Rewilding in terrestrial or freshwater systems has parallels and differences with rewilding in the sea.

Click on each heading below to learn more:

Credit: Mediterranean Conservation Society (AKD).

As you have seen from the example of hunting concessions in Croatia's Velebit Mountains in Module 4, one way to reduce human pressure on a landscape is for rewilders to acquire hunting rights and then reduce hunting pressure to an absolute minimum. This change in management works to support rewilding.

In the ocean a similar move to reduce human pressure is by acquiring fishing rights and then reducing fishing to the minimum legal level, mirroring the acquisition of hunting rights by terrestrial rewilders. Learn more about this approach by reading this article Conservationists buy fishing licence in Great Barrier Reef to create net-free safe haven for dugongs (Hinchliffe, 2022).

Active and passive marine rewilding

Just as on land, marine rewilding can be ‘passive’ – letting nature lead and seeing what happens next. Or, when needed, it can include active interventions to help natural processes return. These interventions can be divided further into practical habitat restoration efforts and species reintroductions.

First, we will look at passive restoration, where nature leads its own recovery.

4 Passive marine rewilding

Today, the seas around Europe continue to be fished at unsustainable levels, while the amount of fish being caught drops every year. Fishing pressure needs to be reduced to allow fish stocks to recover.

Laws, policies, and voluntary agreements are the main tools for designating areas of the sea for nature. Laws and policies can dictate how, where, and what people fish, and which other uses are permitted. This enables them to be applied across seascapes at much larger scales than physical demarcation could cover.

4.1 Reducing human pressure: changing where people fish

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

MPAs are an essential tool for ocean conservation. Within them, habitats and wildlife species that make up healthy, functional marine ecosystems are safeguarded.

You have already learned that areas of land may be set aside for the protection of a particular species or habitat. The same is true in the ocean. Some MPAs are designated to protect specific species while others are designed to protect ‘blue carbon’ habitats such as seagrass beds.

Ultimately, the purpose of an MPA is to provide protection from damage caused by people, so that marine species can recover and natural processes like predator–prey interactions can resume. MPAs enable nature to lead the recovery of marine habitats and resources.

MPAs exist in all areas of the marine realm. They can be found in the open ocean far from shore. Some protect the coast while others extend across estuaries and deltas.

Click on each icon below to learn more about MPAs.

Flamingos over saltmarshes in Bahía de Cádiz Natural Park, Cádiz, Andalusia, Spain. Credit: Diego López / Wild Wonders of Europe.

OECMs

Alongside MPAs, there is growing interest in ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECMs). These are defined as managed areas that deliver effective conservation of biodiversity within a given site regardless of whether that is the goal. In the marine context, examples could include measures to conserve fish stocks or protect a shipwreck or marine war grave (WWF, n.d.).

Offshore infrastructure like wind farms also offer opportunities to give space to nature. While they may cause harm to some species the exclusion zones found around such infrastructure sites can prevent destructive human practices. They can also act as artificial reefs and provide valuable habitat for oysters. As with OECMs, these zones can help marine nature to recover: enhancing wild nature within the zone, and also benefitting the surrounding area, as plants, crustaceans, corals, fish and marine mammals spill out beyond the zone boundary.

On the other hand, the development of offshore wind farms can have potentially negative impacts on seabirds, as is the case with terrestrial wind farms. Seabirds risk death by colliding with turbine rotor blades and risk being blocked or displaced from important foraging habitats or migration routes. The impacts of wind farms on birds can be mitigated by siting them carefully, employing a range of technologies and painting the turbines (Plymouth Marine Laboratory, 2024).

4.2 Reducing human pressure – changing how people fish

The overall aim of changing how people fish is to reduce pressure on fish stocks, support their ability to recover and reduce by-catch (fish or other marine species caught unintentionally while trying to catch another type of fish).

The problem of by-catch is significant for birds as well as fish and marine species. It is estimated that 200,000 seabirds may die each year in the EU after being accidentally entangled in fishing nets (Mitchel, 2024).

Click on each list item below to learn more about what hanging fishing practices could include:

White tailed sea eagle, Haliaeetus albicilla, from fishing boat, on sea eagle safari tours in the Stettin lagoon, Poland, Oder river delta. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

4.3 Redirecting human pressure – changing what people fish

Another way of enabling the marine environment to recover is to redirect fishing pressure so that invasive alien species are caught instead.

Warmer sea temperatures mean invasive alien species are now often able to colonise new areas of the ocean. This can have a devastating impact on native fish species, depleting the stocks of fish that were once traditionally harvested, affecting people’s livelihoods as well as the ecosystem.

Redirecting fishing pressure so that invasive alien species are caught is similar to removing such species in a terrestrial context. The aim is to reduce the new pressure from alien species enough to let native species recolonise parts of the ocean and become more resilient to future changes.

In a marine context the goal is rarely to remove the invasive alien species completely. Instead, the aim is to provide an opportunity for the ecosystem to recover and find a new equilibrium, where these species are naturally held in balance by others.

Fishing in Europe is primarily a commercial activity. For fishers to prioritise fishing for invasive alien species there must be market demand for them.

4.4 Case study – Gökova Bay, Türkiye

Thanks to the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme for all the information in this case study

Context

Where the Central Aegean and the Northeast Levantine Seas meet, Mediterranean waters provide critical habitat for some of its most charismatic species, including sandbar sharks, loggerhead turtles and Mediterranean monk seals.

These waters have long provided local people with sustainable livelihoods through fishing. But this traditional way of life is being threatened by illegal and unregulated fishing activity, damage from tourism, and invasive species from the Red Sea.

In the Gökova Bay to Cape Gelidonya seascape, along the Turkish Mediterranean coast, over 70,000 people still depend on the sea – particularly fishing. Local communities here have been seriously affected by declining fish populations. Over the last 15 years there has been a sharp decrease in catch size causing thousands of people to lose their income.

The local NGO Mediterranean Conservation Society (AKD), supported by the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and Fauna & Flora International, is working to help nature return to the Mediterranean, enhance resilience to the invasive alien species that are entering from the Red Sea via the Suez Canal and revitalise local livelihoods.

One approach is to generate market demand for invasive species, particularly lionfish, so they become an economic asset. This encourages fishers to preferentially harvest these fish, which in turn gives space for other species to bounce back.

Taking action

Read this article, A festival of invasive food, to learn how a restoration effort worked with fishers, chefs and a TV celebrity to reduce pressure on the marine environment and allow it to naturally recover.

Now read how the same creative group found a way to add even more value to the local economy by using the spines of lionfish as a resource for making jewellery in this article Turning venomous spines into jewellery (Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme, 2024).

|

5 Legal protection of species

As with terrestrial animals, many marine wildlife species are protected under various local, regional, national, and global laws and treaties. Legislation has, in some cases, helped species to recover. Populations of humpback whales, for example, have grown since a whaling moratorium was imposed in the mid-1980s (International Whaling Commission).

Yet despite the protection of individual marine species through legislative processes, many populations continue to decline.

Click on the buttons below to view two examples.

When it comes to efforts to conserve and enhance populations of a particular marine species it is not just their direct protection that is important. Adequate protection of their prey is also critical. For example, the lack of protection for sand eels in the North Sea may have negatively impacted populations of harbour porpoises and dolphins, for whom these small fish are an important dietary component (JNCC, 2015).

When it comes to the recovery of marine wildlife populations and natural processes it is not enough to simply rely on protective laws. Building public support and reducing consumer demand for marine products are also critical to ensuring that laws and policies are respected and enforced.

6 Active rewilding in the sea

Active rewilding is a deeply intensive process, due to the equipment, trained divers and boats needed. To date, the focus has mainly been on reintroductions and habitat restoration but with greater global ambition this is beginning to change.

6.1 Species reintroductions

As on land, reintroductions and population reinforcements can help the process of natural recovery to get started.

They are particularly useful:

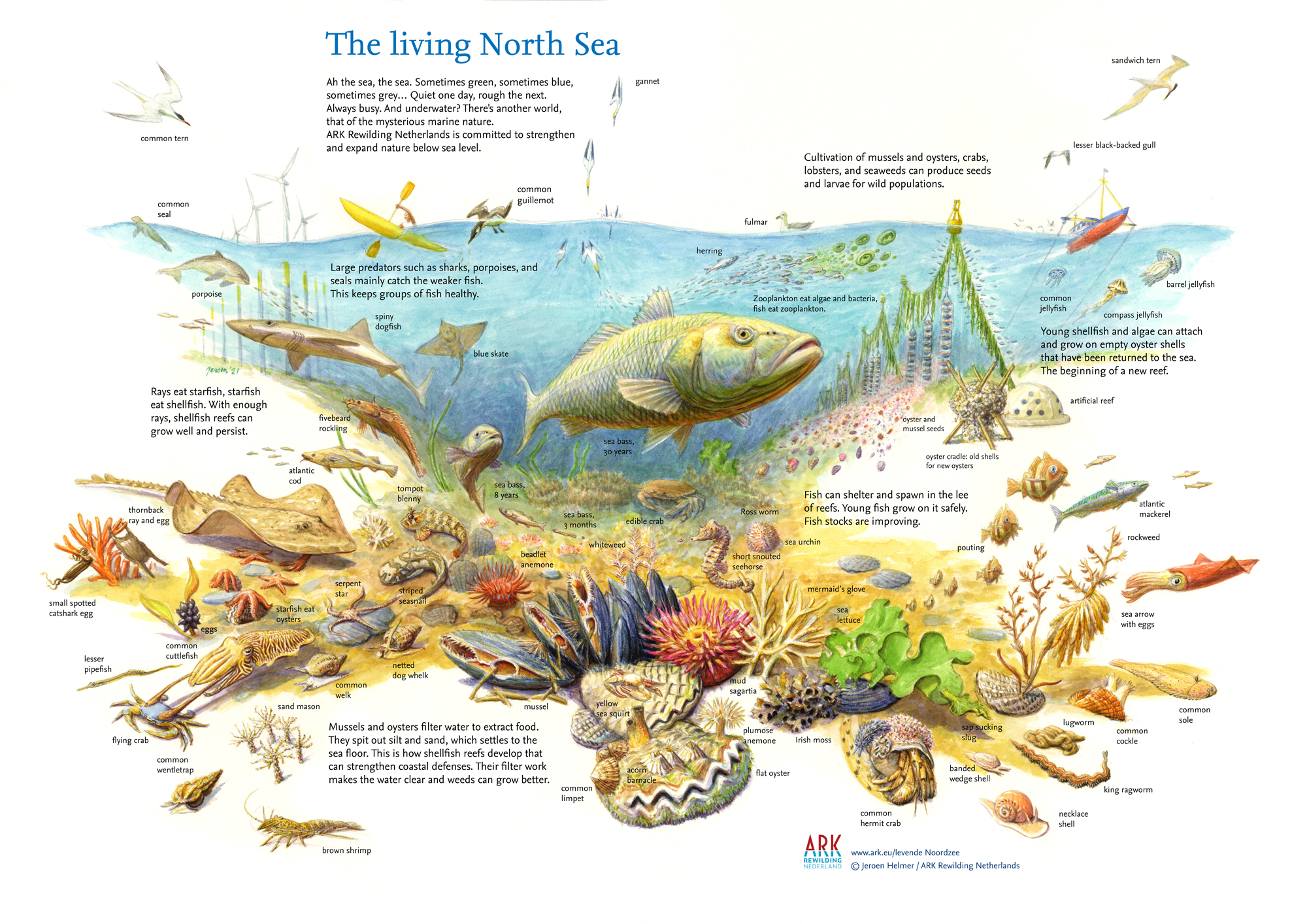

The illustration below depicts the trophic chains in the North Sea. Take a moment to reflect in the interactions and natural processes in this image.

The trophic chains in the North Sea.

Click here for an enlarged version of the above image.

Some examples of marine species reintroductions and reinforcements in Europe are:

- Sturgeon reintroductions and reinforcements in Germany.

- Seagrass planting in the UK and France.

6.2 Habitats

Active marine rewilding can also take a habitat focus.

Saltmarsh is a natural habitat that absorbs storm surges onto land, reducing the impact of flooding and providing important habitat for coastal plants, mammals and birds. In the past, saltmarsh was drained, built over for development and agricultural purposes or polluted, meaning that these important ecological functions were lost.

Saltmarsh restoration can be expensive and some initiatives have been taking place for many years. For example, restoration of Wallasea Island, a saltmarsh habitat in the east of the UK, began almost twenty years ago.

More recently, materials such as coir and rope have been used to help salt marshes recover, and students have been engaged to keep monitoring costs low. Watch this video (Essex Wildlife Trust, 2021) to find out more about this approach:

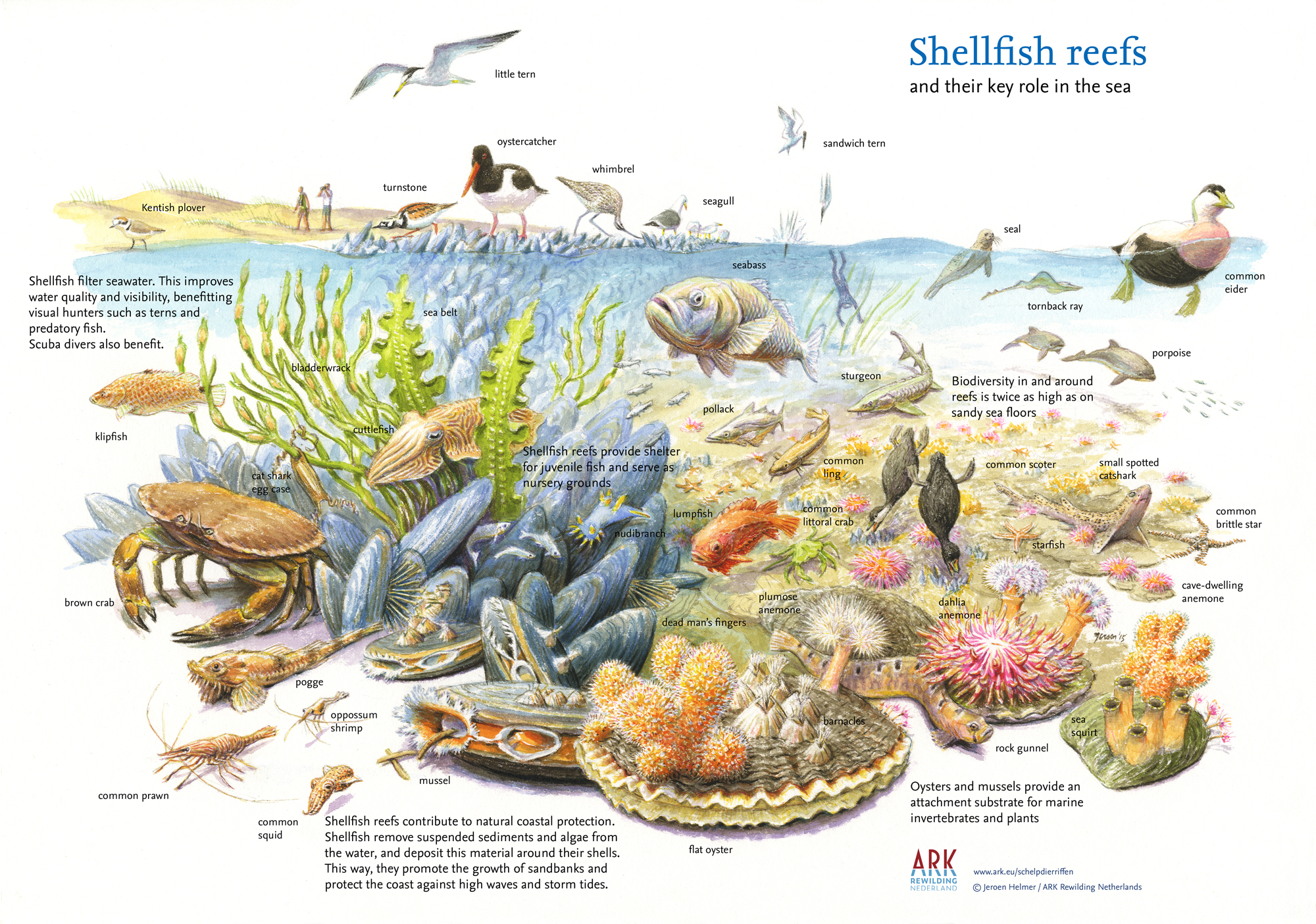

Oysters are a crucial component of global ocean health, as both a species and a habitat creator. These animals filter and clean the surrounding water. Dense oyster colonies fuse together to form reefs that create habitat for numerous species. Mussels, barnacles, and sea anemones settle on oyster reefs, creating abundant food sources for commercially valuable fish such as anchovies, herring, and shrimp.

These can also be known as shellfish reefs. Oyster reefs also provide habitat to forage fish, invertebrates, and other shellfish. In some places, oyster reefs can serve as barriers to storms and tides, preventing erosion and protecting productive estuary waters.

Shellfish reefs and their key role in the sea.

Click here for an enlarged version of this interactive.

Now is a good time to revisit the film by Oyster Heaven (from Module 4) about their efforts to restore oyster beds at scale.

Large-scale and long-running native oyster restoration projects are also taking place in the Netherlands, Scotland, USA and Australia.

6.3 Case Study – the UK Solent and New York City

The Solent waterway is one of the most heavily used in the UK with 79,000 shipping movements each year. However, the area is still of high value to nature, with important saltmarsh, seagrass and mudflat habitats, and over 80% of the coastline in this area already designated for nature conservation.

Blue Marine Foundation and their partners, supported by the Endangered Landscapes and Seascapes Programme, are working to catalyse seascape scale recovery across the 52,200 ha that make up the Solent (Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme, n.d.).

Read about the Solent seascape restoration on the Endangered Landscapes and Seascapes Programme website.

Restoration in such a heavily used area is challenging, but it isn’t new. Blue Marine Foundation were able to take inspiration from an initiative in the USA that has already been running for 10 years.

Once home to 220,000 acres of oyster reefs, by 1927 the last of the commercial oyster beds in New York City was closed and the population of native oysters had collapsed. The huge increase in pollution entering the city’s harbour along with the incessant harvesting meant that the return of the oyster population would not be possible without active restoration.

In 2014, the Billion Oyster Project (n.d.) set out to achieve the goal of restoring one billion oysters to New York harbour by 2035. By 2000, the water quality in the harbour had returned to a level that was enough for oysters to begin to survive again. 10 years later, over 150 million oysters have been restored and over 20,000 students, volunteers, and community scientists have joined the effort, showing how important education, inspiration and involvement are to a successful rewilding initiative.

Learn more at the Billion Oyster Project.

7 Working at seascape scale

Like on land, we need transformative change in how the seas are used to allow natural processes to recover. Moving on from species and habitats, there is an increasing recognition that marine recovery has to happen at ‘seascape’ scale.

Active restoration efforts are costly. Breeding, transporting and reintroducing species, and manually planting seagrass is expensive work. Costs are higher than on land as scuba equipment, trained divers and expensive safety gear are essential.

For this reason, rewilding offers an excellent approach to restoring the seas. Letting nature lead and intervening only when needed means that the costs involved in nature recovery are kept to realistic values.

Click on each icon below to learn more about how, in the sea, rewilding at seascape scale can mean combining the following.

8 Financing rewilding in the sea

The gap between the need for restoration and the finances available is dramatic. This is why we can’t continue as we are, but instead have to adopt new, practical approaches such as rewilding.

While letting nature lead helps to keep costs low, creating space for nature in the sea can still incur costs.

Areas designated for nature may need to be patrolled to deter illegal fishing and generating new revenues for coastal communities needs inputs of time, expertise and potentially commercial loans.

The Sea Ranger Service (n.d.) is a social enterprise dedicated to ocean conservation and marine rewilding. They provide maritime training, employment and coaching opportunities to young people in coastal areas, preparing them for careers in the maritime industry. Simultaneously, they deliver offshore services to assist governments with the management, conservation and restoration of marine environments.

Their initiatives include planting seagrass, conducting hydrographic surveys and monitoring marine protected areas (MPAs). By combining social impact with environmental restoration, the Sea Ranger Service aims to restore one million hectares of ocean biodiversity by 2040 while fostering the next generation of maritime professionals.

A potential avenue to fund the costs of these activities is through the biodiversity and carbon credit markets (see Module 4). The opportunity for companies to invest in the restoration of degraded marine ecosystems and voluntarily offset their activities is being explored by scientists, NGOs and policy makers.

Most of the initiatives to rewild the ocean or coastal zones by actively restoring habitats and reintroducing species are relatively new. There is large scope for reducing costs through technology improvements or scaling.

Shortfin pilot whales underwater in Canary Islands, Spain, Europe. Credit: Iñaki Relanzon/ Wild Wonders of Europe.

9 Building engagement in a marine context

Rewilding in the marine context means working with a wide range of stakeholders. As you saw in Module 3, there are different categories of stakeholders that are relevant in all contexts.

Click on each of the headings below to see the types of people in each category in a marine context:

|

10 Module summary

The planet has lost huge numbers of marine species and habitats. Rewilding the ocean and coastal zones offers a chance to return to a thriving and healthy environment for people and nature.

Multiple individual species and habitats are being actively restored, such as seagrass, coral and oysters. However, a truly integrated 'seascape' approach, that considers the ecosystem as a whole, is still in its infancy but gaining momentum.

Whatever the scale, communities and local interests can be involved and a just and fair transition to a healthier marine ecosystem, which includes people and nature together, is the ultimate aim.

The perfect combination to facilitate rewilding of the ocean and coastal zones is to protect, actively restore, reintroduce species and remove pressures. The opportunities are out there!

We would like to give special thanks to Blue Marine Foundation for sharing their knowledge for this module.

![]()

Now that you have completed this module, you should be able to:

- Determine what rewilding principles are most relevant and suitable to rewilding seascapes.

- Explain the ecological, social, climatic and economic importance of marine ecosystems.

- Assess the impacts of key threats to marine ecosystems and how they disrupt natural processes.

- Compare different approaches to rewilding within the marine environment.

- Evaluate the role of keystone species and natural processes in maintaining healthy marine ecosystems and assess how their restoration can enhance ecological balance.

- Analyse case studies of marine rewilding in Europe.

- Compare the similarities and differences between terrestrial and marine rewilding.

10.1 Further reading

Pétillon, J. (2023) ‘Top ten priorities for global saltmarsh restoration, conservation and ecosystem service research’. Science of The Total Environment, Volume 898, 2023, 165544, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165544.

Discover Wildlife (n.d.) What is shark finning and why is it a problem? https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/fish/what-is-shark-finning-and-why-is-it-a-problem

UNESCO World Heritage Centre (n.d.) Financing marine protected areas through blue carbon credits. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2614 (Accessed 16 April 2025)

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (n.d.) Ocean Acidification. https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/ocean-coasts/ocean-acidification (Accessed 15 April 2025)

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2023) 90% of fish stocks are used up – fisheries subsidies must stop. https://unctad.org/news/90-fish-stocks-are-used-fisheries-subsidies-must-stop (Accessed 16 April 2025)

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (n.d.) Management practices differ widely across fisheries. https://www.oecd.org/agriculture/topics/fisheries-and-aquaculture/fisheries-management.htm (Accessed 16 April 2025)

Restoration Funders (n.d.) Global Marine Restoration. https://restorationfunders.com/marine-restoration (Accessed 16 April 2025)

10.2 Module 7 quiz

Now it’s time to complete the Module 7 quiz – it’s a great way to check your understanding of the course content.

This quiz contains 5 questions and a pass mark of 60% and above is required if you'd like to be awarded your Module 7 – Marine rewilding digital badge.

You can review the answers you gave, and which were correct/incorrect, after each attempt has been completed.

If you don’t pass the quiz at the first attempt, you are allowed as many attempts as you need to pass.