What is rewilding and why is it important?

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Introduction to Rewilding |

| Book: | What is rewilding and why is it important? |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 4:10 AM |

Introduction

In this module you will learn about the main concepts and principles of rewilding and how they serve as a holistic approach to ecological restoration.

You will explore what sets rewilding apart from other restoration and conservation approaches, highlighting its unique benefits and applications.

You will learn how rewilding connects to broader social, political and environmental issues, such as land use change and climate change. Importantly, you will learn to ‘think big’ – to take inspiration from the past to imagine a bold new future for nature in Europe.

![]() Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

After completing this module, you should be able to:

- Correctly identify the concepts and principles of rewilding, in relation to their context, including its benefits for nature and people, and its ‘big picture’ approach to enhancing natural processes.

- Describe the concept of shifting baseline syndrome, its impact on perceptions of ecosystem health, and strategies to counteract it by examining ecological history.

- Recognise how rewilding aims to restore the functional roles of lost wildlife species, focusing on natural processes and interactions to inform future conservation efforts.

- Analyse the causes and socio-economic challenges of rural depopulation and explore how rewilding can transform rural communities and develop nature-based economies.

- Relate the historical and legal context of conservation in Europe and assess the role of protected areas and legal constraints in rewilding efforts.

- Analyse how rewilding can serve as a nature-based solution to climate change by restoring carbon-rich ecosystems, enhancing natural carbon capture, and promoting climate resilience for both nature and people.

Watch this introductory video, in which Frans Schepers shares his rewilding vision with you.

1 Rewilding and ‘big picture’ thinking

In this first part of the course you will look at what rewilding means and the general principles of rewilding. You will also explore a holistic approach to rewilding and present definitions of rewilding.

Flight shots over the Arda river canyon, Madzharovo, Eastern Rhodope mountains, Bulgaria. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

1.1 What is rewilding?

Rewilding is a progressive and inspirational approach to conservation focused on nature and people.

It's about trusting nature to take care of itself, enabling natural processes to shape land and sea, repair damaged ecosystems and restore degraded landscapes. Through rewilding, wildlife's natural rhythms create wilder, more biodiverse habitats.

Rewilding explores new ways for people to enjoy and earn a fair and sustainable living from wilder nature.

Dumbrava, Domogled National park in Southern Carpathians, Romania – a Rewilding Europe site. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

A holistic approach

According to The Global Charter for Rewilding the Earth, rewilding means ‘allowing natural processes to shape whole ecosystems so that they work in all their colourful complexity to give life to the land and the seas’ (Wild11, 2020).

Use the Next and Prev buttons below to view the many forms this can take and use the full-screen icon to enlarge the images.

Definitions of rewilding

There are many definitions of rewilding, some of which include other perspectives on subjects such as species reintroduction, self-sustaining ecosystems, and ecosystem function.

During this course, we will focus on rewilding as a progressive approach to conservation. An approach that enables nature to take care of itself through the restoration of natural processes.

Rewilding's focus on creating self-sustaining ecosystems, and taking action to restore natural processes, sets it apart from other types of conservation and restoration. It embraces a degree of uncertainty, with a long-term, open-ended outlook.

This contrasts with more traditional forms of conservation, which typically focus on the protection of certain species or the attainment of specific targets over defined timelines.

Use the Next and Prev buttons below to view the many forms this can take and use the full-screen icon to enlarge the images.

1.2 The principles of rewilding

Rewilding practitioners from across Europe have developed a set of 11 principles of rewilding. These help to characterise and guide rewilding in a European context.

|

1.3 The rewilding mindset

Rewilding means working at scale, across entire landscapes, to rebuild wildlife diversity and abundance.

It means restoring natural processes and giving them the space and freedom to enhance the functionality and resilience of entire ecosystems. It also means taking inspiration from far in the past to create a bold new vision for the future.

Rewilding principles

To ensure sustained positive effects on biodiversity and resilient ecosystems for future generations, rewilding efforts aim and work on a long-term perspective.

Rewilding means working at scale to rebuild wildlife diversity and abundance and giving natural processes the opportunity to enhance ecosystem resilience, with enough space to allow nature to drive the changes and shape the living systems.

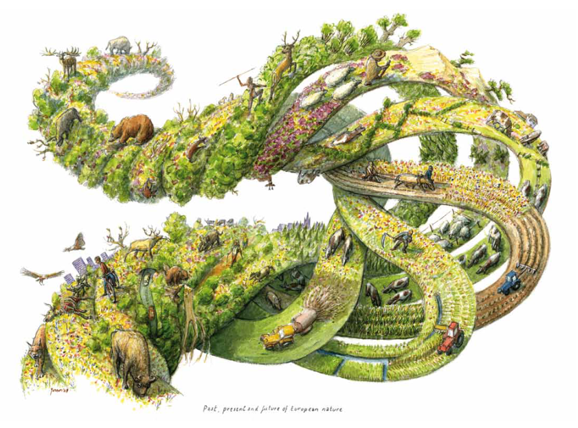

Past, Present and Future of European Nature. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

When we think large-scale and long term, it helps us to put our current situation in context and find new, creative solutions to achieve our imagined future.

This ‘big picture’ approach is what drives rewilding to be transformative and long-lasting – for both nature and people.

Throughout this course, you will have the opportunity to practise using this rewilding mindset. Following a case study from Module 1 to the end of Module 4, you will learn to see what natural processes are missing from a landscape, how they can be brought back, and what opportunities and benefits this could bring.

Before we begin, we need to look deeper at what we mean by ‘natural processes’.

1.4 An introduction to natural processes

Rewilding involves a focus on the return of natural processes into an ecosystem with the aim of making them more self-managing.

But what are the natural processes are we referring to? They are the virtually infinite interactions between and amongst the elements, habitats, and species.

They can vary in scale, from the global carbon cycle to an ant eating a leaf, and timeframe, from photosynthesis happening overnight, to tectonic plates shifting over the course of millennia.

Oxbow lake in side channel of Torne river, Sweden. Credit: Arthur de Bruin.

Some natural processes are driven by the elements, habitats or vegetation, such as weather conditions, geological processes and water-related dynamics. Cold temperatures cause water to freeze, which can split rocks and trigger seeds to germinate. Rushing rivers erode their banks, creating canyons and, later, nutrient-rich sediment deposits, while falling leaves in autumn deliver nutrients back to the soils.

Other natural processes are driven by wildlife itself, such as grazing, seasonal migrations, weather responses, and predator reactions. Dead plankton and other marine life play a crucial role in regulating the climate by storing carbon as it falls to the ocean floor. Salmon carry important nutrients from the sea up into our river systems and soils. The carcasses of animals provide food for others and enrich the earth. Collectively, the eating, breeding, dunging, swimming, flying and trampling of thousands of different species drive the creation of an extraordinary range of different natural processes, habitat types, growth stages, and habitat niches.

Because natural processes are interactions between plants, animals, fungi, bacteria and the environment they are hard to categorise.

Click on each icon below to view four examples.

These interactions continue in an endless web of connections, each part connected to the other in multiple ways. This means that when some interactions and connections are lost, it has impacts throughout the entire system.

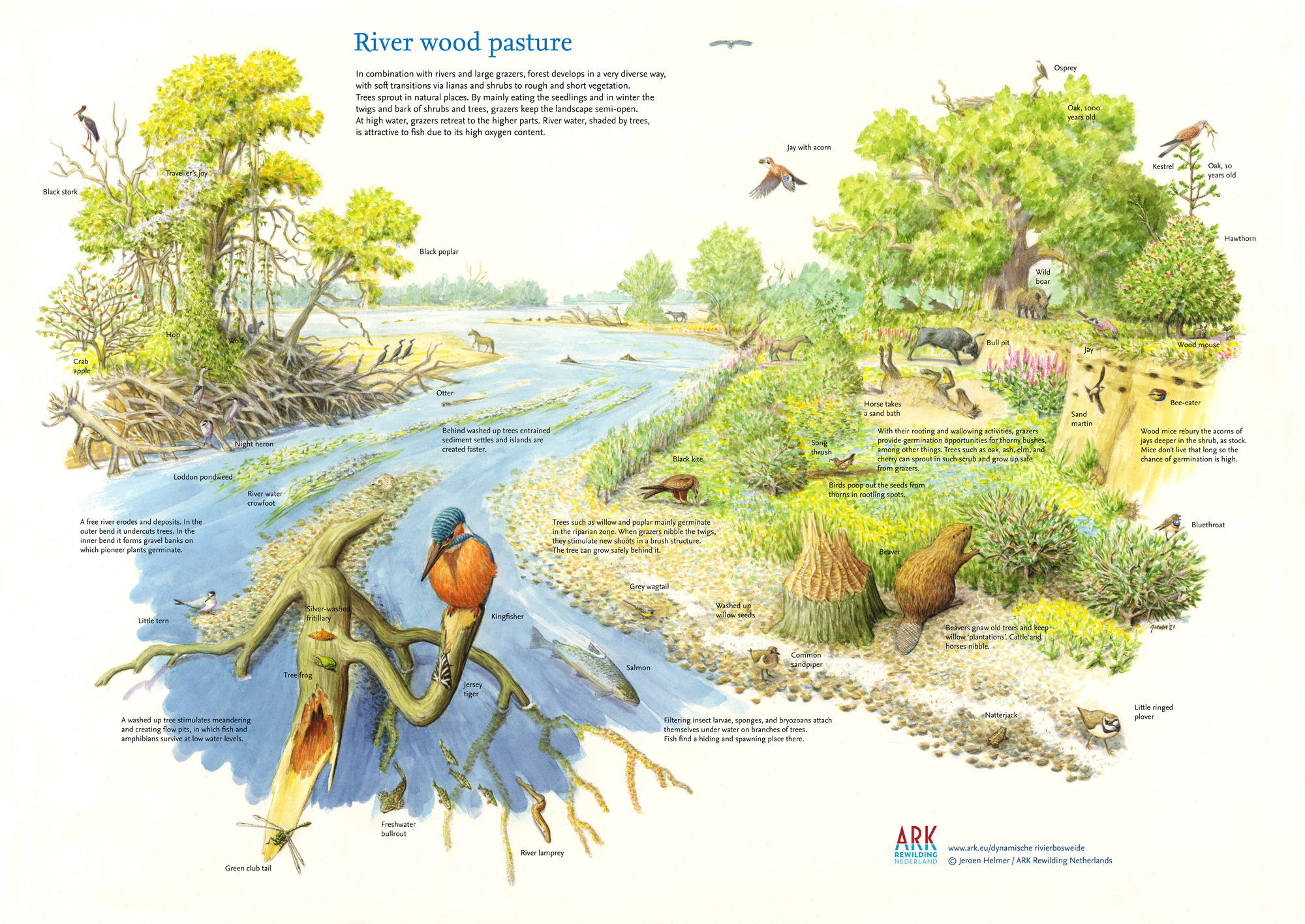

River wood pasture ecosystem. Credit: Jeroen Helmer / ARK Rewilding Netherlands.

Click here for an enlarged version of the above image.

Rewilding aims to restore natural processes by reducing human management and allowing nature to lead its own recovery. This can take many forms, such as removing a dam that allows water to flow more naturally; reducing hunting pressure to allow predator populations to increase and predation and scavenging to resume; or leaving dead wood to decompose in the forest, providing habitat for invertebrates and locking up carbon in the resulting soils.

By allowing natural processes to reshape and enhance ecosystems, rewilding can revitalise land and sea, helping to alleviate some of society’s most pressing challenges and creating spaces where nature and people can thrive in harmony.

Rewilding principle

From the free movement of rivers to natural grazing, habitat succession and predation, rewilding lets restored natural processes shape our landscapes and seascapes in a dynamic way. There is no human-defined optimal point or end state. It goes where nature takes it. By helping nature’s inherent healing powers to gain strength, in the future we will see people intervene with nature less.

In Module 2, we will discuss natural processes in the context of rewilding in more detail, with a particular focus on nature comeback and coexistence.

2 Historical context

In the second part of this module you will look at ‘shifting baseline syndrome’ and its causes and consequences. You also focus on functionality and the key difference between conservation and rewilding.

2.1 Shifting baseline syndrome: causes and consequences

Our experiences and memories inform how we interpret what we see. These experiences and memories are constrained by our age.

The earliest memories a 70-year-old person will have of the wild nature around them will almost certainly differ from the memories that a 10-year-old person will have of the same place. Ongoing biodiversity decline means that the older person will probably remember nature that is wilder and more diverse than the younger person.

The larger the age gap between two people, the greater the difference in how they remember nature becomes.

Eurasian otter, Lutra lutra, Pusztaszer reserve, Hungary. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Wild Wonders.

This age-related difference in how humans remember and perceive the nature around them gives rise to a concept known as ‘shifting baseline syndrome’. A lack of awareness about how landscapes and their wildlife populations looked in the past means their condition today is accepted by most people as completely natural.

For example, when sightings of deer or hedgehogs become rare in a particular area over a long period of time, this rarity eventually becomes seen as normal, because most people don't remember a time when these species were more abundant.

Red deer in the Rhodope Mountains, Bulgaria. Credit: Bogdan Boev / Bogdan Boev Wildlife Photography.

Shifting baseline syndrome has implications for nature conservation. It can lead to increased tolerance of environmental degradation and lower our expectations regarding the health and diversity of ecosystems.

This, in turn, can lessen our willingness and desire to restore nature. It can influence policymakers and, to a lesser extent, those engaged in measures designed to enhance wild nature.

2.2 How can we counteract shifting baseline syndrome?

Education can help to counteract shifting baseline syndrome. Since you are taking this course, you may already know about the biodiversity decline and habitat degradation that has been negatively impacting the natural world for many decades.

Europeans used to share their landscape with woolly mammoths, giant deer, cave lions, and woolly rhinoceros, all of which became extinct between 15,000 and 4,000 years ago.

Time travelling back into the European past further reveals that even more species are now missing from the contemporary landscape in Europe, such as hippopotamus, straight-tusked elephants and interglacial rhinoceros, all of which became extinct around 35,000 years ago (Svenning et al., 2024).

Megafauna diversity and functional declines in Europe from the Last Interglacial (LIG) to the present. Davoli et al. (2023).

A straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), by Julian Fiers. The species inhabited Europe, having become extinct during the latter half of the Last Glacial Period, with the youngest remains found in the Iberian Peninsula, dating to around 44,000 years ago.

This state of co-existence, with Europeans living alongside such very large animals (megafauna), is so far from our current reality that it is hard to even imagine.

Also, it used to be common to see more interactions between different habitat types. For example, rivers would spill over into their floodplains in spring, depositing sediments and seeds from upstream. This natural interaction between water, soils and vegetation is now rare in Europe: it is more common to see flood defences and embankments along the rivers, with agricultural land or buildings on the floodplains.

Stora Sjöfallet water power station, Greater Laponia rewilding area, Nordic Taiga, Norrbotten, Sweden; Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

If we take a time period thousands of years ago as a baseline, any assessment of the status of contemporary European nature will find it severely degraded, with many important species missing, and an environment that has been transformed from mostly natural to one that has been substantially urbanised and industrialised. Losing interactions between different elements of the ecosystem means we lose the vital ecological roles they play.

2.3 Focus on functionality

Click on each list item below to learn more about the key difference between conservation and rewilding:

Humans have impacted their natural environment throughout history – in more recent times, this impact has intensified. Many species have been driven to extinction since the last ice age. The aurochs (the ancestor of domestic cattle), for example, was hunted to extinction in Europe in the seventeenth century. European bison had been driven to the edge of extinction by the twentieth century, while wolves became extinct in Britain in the 1700s.

A wide range of other European animal and plant species have become locally extinct or less common over the last few thousand years, from brown bears and Eurasian lynx to Dalmatian pelicans and Atlantic sturgeon.

A Eurasian lynx in Nordic Taiga. Credit: Daniel Allen / Rewilding Europe.

Instead of trying to restore nature to a historic baseline, rewilding looks to the future, with the aim of restoring natural processes and ecological functioning. This can often be achieved by focusing on proxy species. The beneficial natural grazing impact of the aurochs, for example, can be restored by reintroducing and enhancing populations of other wild herbivores that are in existence today.

Remembering the past can help us to understand how much contemporary European nature has been depleted. It can challenge shifting baseline syndrome, help us to ‘think big’, and inspire us in terms of moving towards a natural world that is healthier, more abundant, and more ecologically functional.

|

‘A landscape without animals is like a stage without actors’ – Frans Schepers |

|

3 Social context: rural depopulation and opportunities for rewilding

Europe is a dynamic continent. As well as changes in nature over time, changes in the way humans live have affected how we use the land, fresh water, and the sea.

3.1 The challenge and opportunity of rural depopulation

People have been moving from rural areas to towns and cities across Europe for decades. As a result, more than two-thirds of the EU population now live in urban areas.

The shift of people away from agricultural production in rural areas is widely referred to as ‘land abandonment’. Recent estimates indicated that around 30% of agricultural areas in the EU are under at least a moderate risk of land abandonment by 2030 (Castillo et al., 2018). While ‘abandonment’ is hard to define and measure, it suggests that the landowner or user has made a choice to leave, which is not always the case.

Rural depopulation means an increasing amount of land across Europe is being left with little or no human management or usage. As people leave, many rural communities across the continent face huge socio-economic challenges, as services such as shops and schools become unviable, and jobs become scarce.

Abandoned house in the Rhodope Mountains, Bulgaria. Credit: Staffan Widstrand / Rewilding Europe.

Rural depopulation and land abandonment also offer a huge opportunity for rewilding. As more and more land ceases to be managed by humans, there is more space for nature to recover, which can help to address issues such as climate change.

There is also a growing opportunity for rewilding – as a holistic approach to conservation – to provide a new and optimistic outlook for rural communities through the development of sustainable, nature-positive economies. As such economies develop and provide jobs and income, they can help to revitalise areas by encouraging people to return and repopulate rural areas.

You will explore the economic opportunities of rewilding and the connection between rewilding and climate change later in this course.

What people leaving does to the land

Rural depopulation and land abandonment are leading to the decline and disappearance of animal husbandry across many parts of Europe. This, in turn, means many European landscapes are experiencing a significant decrease in grazing. At natural population densities, herbivores can help to promote semi-open, biodiverse landscapes through their grazing impact. By reducing the amount of combustible vegetation in the landscape and creating natural firebreaks, they can also reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire outbreaks.

In places where people are no longer grazing animals, shrubs and other woody vegetation can start to take over. In some situations, this can negatively impact biodiversity and the cultural value of the landscape. It also heightens the risk of catastrophic wildfires breaking out. Such wildfires are becoming increasingly common in many European landscapes as climate change leads to longer droughts and more extreme heatwaves. They can reduce biodiversity, damage property, and lead to loss of human life.

In such places, the reintroduction and restocking of free-roaming populations of wild and semi-wild herbivores, such as European bison, deer, horses, and Tauros, can be an important contribution to reducing the risk and impact of fires (Johnson et al., 2018). This is why populations of such wild herbivores are often known as ‘grazing fire brigades’. Read the article Rewilding – the natural way to minimise wildfire risk to learn more about this.

European bison in De Maashorst, The Netherlands. Credit: Hans Koster.

However, the changes in the ecosystem as people leave and nature recovers vary with context.

Natural forest regrowth on unmanaged fields and pastures has contributed significantly to the increase in Europe's forest cover over many decades. Between 2000 and 2020 there was a 5.5% increase in forest cover across European countries. This is an ongoing upward trend.

Fewer people and more forest cover can improve the conditions for wildlife comeback, particularly when combined with stronger protection measures for certain species, such as raptors and large carnivores, as well as improved hunting regulations and practices. Birds, mammals and reptiles have all spontaneously returned to new areas across Europe.

The natural regeneration of forests can also capture carbon, helping to mitigate climate change, and deadwood provides a rich habitat for many invertebrates, providing food for birds and mammals and re-starting the circle of life.

3.2 Rewilding generates new economic opportunities

As one of its principles, rewilding aims to build nature-based economies. Rewilding and the recovery of nature offer tremendous possibilities to develop new and sustainable nature-based businesses in rural areas, with nature representing a vital asset for the business, rather than a consumable resource.

Rewilding principle

Through enhancing wildlife and ecosystems, rewilding provides new economic opportunities and income linked to nature’s vitality.

Unmanaged land is often situated alongside land that continues to be used for farming and forestry. This means that low-intensity and traditional farming systems are increasingly coexisting with wilder nature.

While this can generate specific challenges, such as predation on livestock by wildlife or wildlife damage to crops, it also brings economic opportunities, such as wildlife-friendly food and drink products, hospitality for nature-positive tourism, or wildlife photography tours.

La Maleza Safari Tours in the Iberian Highlands, Tourists in Jeep. Credit: Lidia Valverde / Rewilding Spain.

This can create or sustain jobs in remote parts of Europe where the loss of even one family can cause a school or shop to close, impacting the wellbeing of many others.

Rewilding can also generate new financial flows to areas with low populations in the form of carbon or biodiversity credits. This can be an important economic incentive for local people who support rewilding on land that was previously farmed.

3.3 Rewilding provides hope

Wild nature can be the return of wild animals. It can also be the presence of dead trees, decaying carcasses or rivers that spill over their banks into their floodplains.

Wild nature is messy and unpredictable. To bring that back to Europe we need hearts and minds that embrace it.

The role of people – in and around rewilding areas

It's a popular misconception among those not familiar with rewilding that it's all about nature and not about people. Yet engaging and inspiring people of all backgrounds and ensuring they benefit from nature recovery is vital to the success of rewilding efforts.

People living and working in and around areas that are being rewilded have a critical role to play in the rewilding process – from shepherds, teachers, local officials, and hotel owners to ecologists, lawyers, and artists.

Rewilding principles

Rewilding embraces the role of people, and their cultural and economic connections to the land. It is about finding ways to work and live within healthy, natural vibrant ecosystems and reconnect with wild nature. We approach rewilding with a long-term knowledge of the environmental and cultural history of a place.

Building coalitions and providing support based on respect, trust and shared values. Connecting people of all backgrounds to co-create innovative ways of rewilding and deliver the best outcomes for communities and wild nature.

Community engagement event in Italy on coexistence with the wolf. Credit: Io Non Ho Paura Del Lupo.

The role of people – across Europe

It is not only people living in and around rewilding areas that have an important role to play.

Research shows that hope inspires action and promotes long-term care for the natural world. To truly restore nature across Europe, we therefore have to provide hope and inspiration, to motivate behaviours now that will lead to a more positive future.

This is essential in Europe. Here, worries, anxieties and feelings of depression about war, climate change and loss of biodiversity, unemployment and rising living costs, and the pressures of social media, have all made the already-poor levels of mental health worse.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, one in six people in the EU were living with mental health issues. By 2023, this had risen to almost half of Europeans – 46% of people experienced an emotional or psychosocial problem such as feeling depressed or anxious in the past 12 months (European Commission, 2024a).

Rewilding provides hope because it is positive and inspirational. This provides a contrasting narrative to the more negative messages that dominated conservation in the twentieth century. Rewilding embraces and empowers people, encourages us to reconnect with and live alongside nature, and provides a way for everyone to make a positive difference.

Rewilding principle

Rewilding generates visions of a better future for people and nature that inspire and empower. The rewilding narrative not only tells the story of a richer, more vital tomorrow, but also encourages practical action and collaboration today.

The role of society – acting today for a wilder and better tomorrow

Policies, economic activities, recreation, and transport choices all affect nature. Every time we vote, make a purchase, invest or take a journey, our decisions have an impact on the natural world.

Imagining a positive future for nature in Europe can inspire us to make the decisions and choices that help to realise that future. Our actions today determine whether we will reach our goal of a wilder Europe.

Pair of Wildling Shoes Perto. Credit: Wildling Shoes.

Brands have been slowly moving towards more sustainable and environmentally conscious production.

Wildling Shoes, based in Germany, already has a long history of this type of production and has now developed, in partnership with Rewilding Portugal, a new shoe called Perto which goes even further. A shoe that supports producers who live in a positive way with the Iberian wolf, supported by the LIFE WolFlux project. So anyone can ‘support’ rewilding initiatives through their day-to-day choices.

Rewilding aims to foster a paradigm shift in the way people in Europe and across the world understand and value nature. This will require a change in mindsets, expectations and behaviours. You will learn more about the importance of engaging with people and communicating hope in Module 3.

By taking this course you are already part of this change.

4 The legal and policy context of rewilding

It is not only businesses and everyday citizens that have a part to play in enabling rewilding.

Governments and institutions such as the European Union have perhaps the most important role, through their ability to facilitate or constrain actions that affect the return of wild nature.

4.1 Global commitments

At a global level, the need for ecological restoration is enshrined in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and in the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was adopted in 2022. It includes what is known as the ‘30 by 30’ target: a global initiative for governments to designate 30% of the world's land and seas as protected areas (or other effective area-based conservation measures) by the year 2030. Most countries in the world, and also organisations such as the European Union, have committed to achieving these targets.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 global goals established by the United Nations in 2015 as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include nature restoration. SDG 15 focuses on life on land, with the mission to ‘protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss’ (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.b).

SDG 14 is also about nature, focusing on life below water. The mission here is to ‘conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development’ (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.a). Although SDG 14 does not explicitly refer to reversing ecological degradation or nature restoration, sustainable use and protection of marine and coastal environments enables spill over from protected areas into the wider waters with the resulting benefits for nature. You will learn more about rewilding in a marine context in Module 7.

The Intergovernmental Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) released in 2024 the IPBES Nexus Assessment, which examines the complex and interconnected relationships between biodiversity, water, food, health, and climate change. It analyses how these ‘nexus’ elements interact and influence each other, considering the impacts of human activities and exploring potential pathways towards more sustainable development (McElwee et al., 2024).

The assessment aims to provide policymakers and other stakeholders with a comprehensive understanding of these interlinkages to inform integrated decision-making and promote actions that simultaneously address multiple societal challenges.

Cover of the IPBES Nexus Assessment. Credit: IPBES.

4.2 The European perspective

Within the European Union (EU), the need to restore nature has now also been formally recognised.

A momentous milestone was reached in June 2024 with the adoption of the EU Nature Restoration Regulation, widely referred to as the Nature Restoration Law.

The Nature Restoration Law commits EU Member States ‘the long-term and sustained recovery of biodiverse and resilient ecosystems across the Member States’ land and sea areas through the restoration of degraded ecosystems’. (European Commission, 2024b, art. 1.a.)

Read this Regulation - EU - 2024/1991 - EN - EUR-Lex if you would like to learn more.

Each EU Member State is required to create a National Nature Restoration Plan by mid-2026. This must include specific sites and habitat types for restoration, as well as connections to other policies and goals, and ways to fund the restoration activities.

Rewilding has an important role to play in helping EU Member States achieve their regional and international restoration targets.

In trusting nature to manage and restore itself, rewilding can be a very cost-effective way of achieving restoration goals, enhancing biodiversity and addressing climate change. This heightens its appeal in a time when government budgets are under pressure from a wide range of other factors.

4.3 Building on a long history of conservation and protection

Restoration is becoming more prominent in policy and law. However, commitment to protecting nature in Europe is not new and some of the oldest legislation within the European Union relates to nature.

Click on each box below to read more.

As a result of these directives, new protected areas were established across the EU.

Protected areas are the backbone of European nature. With more than 100,000 sites designated across the EU alone, such areas cover nearly 1.1 million square kilometres, or 26.1% of EU land (EEA, 2024), with many additional protected areas across Europe and in the sea.

Many of Europe’s protected areas contain unique and frequently awe-inspiring repositories of biodiversity. Yet simply protecting the nature they currently contain isn’t enough to reverse biodiversity decline or slow climate change.

This large area of land already recognised for nature means there is now an opportunity to build on conservation efforts and enhance the invaluable nature they already contain. Rewilding within protected areas can restore natural processes, support the return of European wildlife species, and inspire the millions of people who visit each year to care for nature.

Sunset view of mountain ridges in the Abruzzo National Park showing the characteristic landscape of the Central Apennines in Italy. Credit: Bruno D'Amicis / Rewilding Europe.

You already learned that one of the rewilding principles is acting at nature’s scale. Many protected areas are huge and offer a fantastic opportunity for rewilding.

Others are much smaller in size and through the Birds and Habitats Directives, are protected for a particular habitat or species. This means that they may not always be suitable for rewilding.

This is for two reasons:

- As nature recovers habitats may change, particularly where they have been intensively managed to protect a specific species.

- Rewilding is an open-ended, dynamic process that aims for the recovery of nature processes, some of which require large areas.

In smaller places, rewilding adds value around the protected area by creating areas and space where threatened habitats or species may be able to expand, recolonise or adapt to climate change. In this way, rewilding can complement and benefit existing conservation measures.

Rewilding principle

Rewilding complements more established methods of nature conservation. In addition to conserving the most intact remaining habitats and key biodiversity areas, we need to scale up the recovery of nature by restoring lost interactions and restore habitat connectivity.

Marsican brown bear in Abruzzo. Credit: Bruno D'Amicis / Rewilding Europe.

4.4 Constraints of existing laws and policies

The global legal and policy environment has never been more supportive of rewilding. Yet there are still many cases where existing policies and laws constrain practical rewilding efforts by supporting and obligating human management of the environment.

Within the EU it is currently impossible for cattle or horses to be considered wild; they are always classed as domesticated animals. This has important implications for their registration and management. Within a rewilding context – like following a reintroduction or translocation – these animals would ideally be allowed to roam free with little to no human management. However, the law often requires them to be registered, vetted and in some cases provided with supplementary feeding.

Similarly, there are laws that prevent carcasses being left in nature. These laws were introduced to protect human health and ensure food safety in an agricultural environment. In a rewilding context it means that the carcasses of animals that are legally classed as domestic, such as horses and cattle, must be removed from the landscape even if they are living in huge remote areas far from food production. Removing carcasses reduces the food available for scavengers, such as vultures, eagles, foxes and a wide range of invertebrates.

Aviary at Rhodope Mountains, Bulgaria. Credit: Ivo Danchev.

Scavengers of all descriptions are a fundamental part of a healthy ecosystem. Rewilding therefore aims to change or remove laws and policies that prevent these natural processes from taking place, in settings where it is safe to do so.

Rewilders are finding new ways to apply and interpret laws to align them more closely with global and European commitments to restore nature. Rewilders can play a pioneering role by challenging the status quo and finding new ways for laws to be interpreted in order to advance nature recovery across Europe.

Rewilding principle

Rewilding means acting in ways that are innovative, opportunistic and entrepreneurial, with the confidence to learn from failure.

5 Climate change context

In this final part of the first module you will examine the nature–climate connection and how rewilding can be a climate change solution.

You will also explore something that has the potential to be one of the most impactful and immediately employable nature-based climate solutions.

The nature–climate connection

The 2016 Paris Climate Agreement saw almost all of the world's nations commit to reducing the man-made greenhouse gas emissions causing global warming. These nations agreed to pursue efforts to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5°C, which will minimise the risk of extreme climate-related effects – such as catastrophic heatwaves, droughts and wildfires – not to mention many other impacts which will degrade the health and liveability of our planet.

These efforts are currently focused on eliminating carbon dioxide emissions by 2050, through measures such as renewable energy development and electrification.

Yet even if such efforts are completely successful, they will not be enough to achieve the 1.5°C target. This is because there is already too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which now needs to be removed and stored in terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments.

If we are to effectively address climate change we need nature's help to go beyond net zero. And to help nature help us, we need rewilding.

5.1 Rewilding as a nature-based climate change solution

Nature is our best ally in helping to fix climate change. Both animals and the habitats where they live play fundamental and interconnected roles in this cycle.

This means that both are important when it comes to rewilding as a nature-based climate solution.

- Restoring carbon-rich natural ecosystems – such as wild forests, grasslands, seagrass beds, and peatlands – enables them to absorb and store great quantities of carbon.

- Restoring populations of marine, freshwater, and terrestrial animals – particularly large vertebrate species – can also help to massively boost carbon capture and storage.

By restoring natural processes and enabling nature to manage itself, rewilding offers a climate change solution that is often cheaper and more effective than more active restoration approaches, such as planting huge quantities of trees.

Peatland in the Scottish Highlands. Credit: Daniel Allen / Rewilding Europe.

Rewilding principle

By providing and enhancing nature-based solutions, rewilding can help to mitigate environmental, social, economic and climatological challenges.

5.2 Animating the carbon cycle

Research has shown that wildlife populations exert a huge influence on the carbon cycle in terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems through a wide range of processes. Restoring such populations through rewilding to enhance natural carbon capture and storage – known more popularly as ‘Animating the Carbon Cycle’ – has the potential to be one of the most impactful and immediately employable nature-based climate solutions (Schmitz et al., 2023).

Animals influence the carbon cycle in myriad ways. Their impact varies according to both their functional ecological role, and the ecosystem of which they are a part. As animals move around their environment, they trample soils and grasses, browse and break woody plants and create clear areas of bare soil. All of these cause more carbon to be captured, in different ways and in different places, than if the animals were not there. You will learn more about this in Module 2.

Example of Animating the Carbon Cycle in marine coastal and deep ocean ecosystems. Credit: Yale/GRA.

5.3 Adapting to climate change through rewilding

Rewilding can also help nature and people adapt to climate change. This is very important, as further changes to our climate are inevitable, even if the measures we take now eventually bring global warming to a halt.

Rewilding aims to restore landscapes at scale. As such, it can provide space for animals to move and adapt to changing climatic conditions, whether that be from south to north, to higher elevations, or across climate zones.

Rewilding can also boost the resilience of nature to climate change. For example, strengthening wild herbivore populations through translocations can reduce the susceptibility of herds to climate-related stresses such as drought or flooding. Healthy, biodiverse forests are also more resilient to more extreme climatic conditions as the system can respond and adapt in ways that a monoculture plantation could not.

Wild Konik horses, Ermakov Island, Danube Delta, Vulkove, Odessa Oblast, Ukraine. Credit: Andrey Nekrasov / Rewilding Ukraine.

Enhancing climate change adaptation through rewilding can also benefit people. For example, measures to support beaver populations, resulting in more beaver dams, can help to regulate the movement of water through catchment areas. This can decrease the severity of floods and droughts that threaten people's lives and livelihoods. Reconnecting rivers with their floodplains, enabling natural flooding, can provide similar benefits.

Giving space to nature can also promote biodiversity, which has the potential to help people adapt to climate-related challenges in ways that are not yet known. The drought-tolerant crops and medicines for the future will be found in wild nature – not among the species that are already domesticated and selectively bred for specific traits.

Climate change is impacting a wide range of economic activities in Europe and across the world. Farms may become less productive. Ski slopes may close. More extreme temperatures may result in less tourism during summer months. The development of sustainable nature-based economies through rewilding can generate new economic opportunities in places where old ones are no longer viable. We explore this more in Module 4.

Wildlife watching hides in the Velebit Mountains, Croatia, offer a chance to see some of Europe’s most iconic species. Credit: Nino Salkić / Rewilding Velebit.

6 Module summary

You have learned in this first module that rewilding connects to conservation, economics, politics and law, arts and culture, recent times and pre-history. You have also learned that rewilding is not only about nature; it is also fundamentally about people too.

Rewilding is a comprehensive approach that helps nature recover and people to benefit. This means that to rewild, we need people from all backgrounds with skills in many different sectors.

Biologists and ecologists, poets and writers, lawyers and policy makers, farmers and shepherds, drivers and divers – everyone has a role to play.

For this reason, the final rewilding principle is knowledge exchange – as we grow the rewilding movement and find new ways to help nature recover, we share the best-available evidence, knowledge and learning to help us succeed.

Rewilding principle

Exchanging knowledge and expertise to continually refine rewilding best practice and achieve the best possible rewilding results. Using the best-available evidence, gathering and sharing data, and having the confidence to learn from failure will lead to success.

In this module you have studied the principles of rewilding and the context of rewilding in Europe. You have seen how adopting a ‘big picture’ perspective helps us to imagine a positive future that inspires action today.

|

![]()

Now that you have completed this module, you should be able to:

- Correctly identify the concepts and principles of rewilding, in relation to their context, including its benefits for nature and people, and its ‘big picture’ approach to enhancing natural processes.

- Describe the concept of shifting baseline syndrome, its impact on perceptions of ecosystem health, and strategies to counteract it by examining ecological history.

- Recognise how rewilding aims to restore the functional roles of lost wildlife species, focusing on natural processes and interactions to inform future conservation efforts.

- Analyse the causes and socio-economic challenges of rural depopulation and explore how land abandonment and wildlife reintroduction through rewilding can transform rural communities and develop nature-based economies

- Relate the historical and legal context of conservation in Europe and assess the role of protected areas and legal constraints in rewilding efforts.

- Analyse how rewilding can serve as a nature-based solution to climate change by restoring carbon-rich ecosystems, enhancing natural carbon capture and promoting climate resilience for both nature and people.

Next, in Module 2 – Nature recovery, we will look deeper into the ecology of rewilding.

Now have a go at the Module 1 quiz.

6.1 Module 1 quiz

Now it’s time to complete the Module 1 quiz – it’s a great way to check your understanding of the course content.

This quiz contains 5 questions and a pass mark of 60% and above is required if you'd like to be awarded your Module 1 – What is rewilding and why is it important? digital badge.

You can review the answers you gave, and which were correct/incorrect, after each attempt has been completed.

If you don’t pass the quiz at the first attempt, you are allowed as many attempts as you need to pass.