2.4 Links to other languages

In this section you will consider ways in which Scots has been influenced by other languages and, has in turn, influenced English.

As sister languages, Scots and English share a great deal of vocabulary. A common criticism levelled against Scots is that it has no words for modern devices, such as ‘television’. The fact is, however, that it shares such vocabulary with English.

And ‘television’ can be seen as not being English either, coming as it does from the Greek tele- (far) and the Latin vision (seeing). Many other European languages have adopted a similar term:

| Language | Word for ‘television’ |

|---|---|

| Albanian | television |

| Estonian | television |

| French | télévision |

| Italian | television |

| Polish | telewizja |

| Spanish | televisión |

The fact that Scots uses the same word is not, in fact, remarkable then. More remarkable are the languages like German (Fernsehen) which do not adopt the word in the same way.

Scots is also a Germanic language. This can be clearly seen in words such as ken (know), which is limited to certain uses in English (e.g. “to be beyond your ken”), but is very close to the German kennen. Similarly, the Scots and German for ‘light’ are identical – licht.

Scots-speaking travellers to Oslo, and other Scandinavian destinations, will have little trouble reading signs such as the one below:

With the Scots words oot (out) equating to Norweigan ut (Swedish ute and Danish ud) and gang (go) to gang, this seems an entirely logical name for an exit. And those who watch Scandi-crime drama are thrilled to hear how bra (good) everything is in Swedish or Norwegian: braw in Scots (albeit with slightly differing pronunciations). Scots was influenced by Norse languages, due to Viking invasion and settlement, although the languages are all Germanic and these words can trace their roots back that way.

Dutch and Scots share certain words too. A Scots-speaking person might redd (tidy, clear) a room, with the Dutch equivalent being reden. To redd has become an important community activity, which is illustrated by the Shetland Amenity Trust [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] website page on “Da Voar Redd up” which is the UK’s most successful community litter pick!

The Scots word keek (to glance or look sharply) also has a Dutch cognate in kijken. Again, these are both Germanic languages, making links understandable. However, trade links between Scotland and Dutch and Flemish speaking nations strengthened language links too.

France and Scotland formed the Auld Alliance for centuries, and this had a similar influence on trade and language. The Scots dinnae fash yersel (don’t worry, don’t get upset) has roots in the French fâcher (to annoy). The large plate – ashet – found in Scotland (and interestingly New Zealand), is linked to the French assiette.

Latin gave birth to the Romance languages but also had a more direct influence on Scots vocabulary. Many Scots legal terms came straight from Latin, for example ‘procurator fiscal’. Schools too have their share of Scots vocabulary from Latin: where would any school be without the jannie, the diminutive of ‘janitor’? This word for a caretaker made it straight from the Latin into Scots.

Gaelic has given many words to Scots, notably for geographical terms: glen, loch, strath and clachan, which have often become part of place names, as well as specific terms such as ceilidh and skean dhu which form part of Scots and English by virtue of being the best terms for ‘cultural’ nouns.

There is a wide-spread belief that Scots is being corrupted by English in modern times. The influence of the mass media and the internet are blamed for this phenomenon, which is not unique to Scots. Famously, the Académie Française tries to prevent Anglicisation of French. While Modern Scots speakers tend to use English vocabulary at need to supplement their Scots, English has always borrowed words from Scots too.

This includes terms such as blackmail, which originated in the borders in the days of the Reivers; and more positively, cosy and gumption, both originating in 18th Century Scots. A more recent word found in English from Scots is minging, the Scots word mingin, Anglicised by the addition of the characteristic final g.

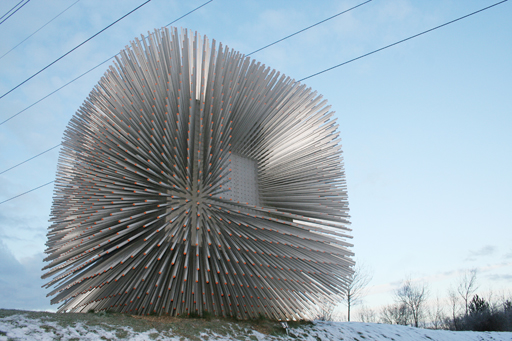

But what of Sitooterie? Here is a picture of Sitooterie II, Barnards Farm, West Horndon, Essex:

This Sitooterie at Barnards Farm was commissioned as “a permanent pavilion to sit within their grounds…The cube was precision-machined, by an aerospace company, from 15mm anodised aluminium and bonded together using special high-strength adhesive…Seating is created by elements that extend into the cube to support a machined aluminium surface”.

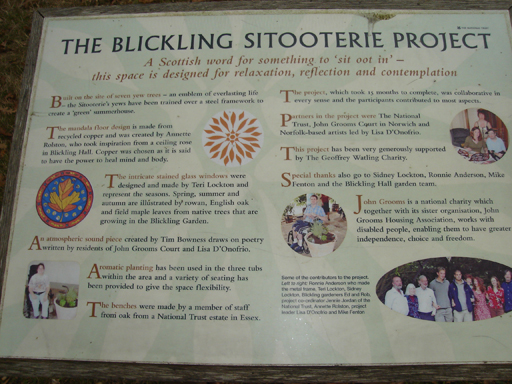

Similarly, Blickling Hall Garden, north of Aylsham in Norfolk, displays the following example of the English language borrowing from Scots:

Scots has borrowed widely from other languages, but continues to exert its own influence on English, as it has done for centuries, to this day. As J Derrick McClure says:

“What this abundant, varied and productive foreign influence should show is that Scots was once the language of a cosmopolitan, adventurous, outward-looking people, whose country, small and isolated though it was, played a full part in the economic, political and artistic life of Europe.”

And finally, accent plays a big part in the spelling of Scots, which is a non-standardised language. This can be seen in the various spellings of dirl; dir(r)le; dirrel – as well as many other Scots words.

The section on Grammar in part two of this course will look more particularly at the peculiarities of Scots grammar, such as the use of thon in our opening sentence Thon’s a braw wee sitooterie ye’v biggit oan tae yer hoose.

And in the unit on Dialect diversity in part one of the course you will explore regional variations of Scots in detail, which is another key reason for spelling variations of Scots words.

2.3 New uses and new vocabulary